A groundbreaking scientific discovery has illuminated a crucial genetic mechanism within a rare but exceptionally dangerous fungus, potentially paving the way for entirely new strategies to combat infections that have necessitated the closure of hospital intensive care units. This significant development offers a glimmer of optimism against a pathogen that has proven exceptionally recalcitrant to existing treatments and notoriously difficult to eradicate once it establishes a foothold in a patient.

The fungus in question, identified as Candida auris, poses a particularly grave risk to individuals whose immune systems are already compromised by severe illness, leaving healthcare facilities exceptionally vulnerable to widespread outbreaks. While the fungus can reside on the skin without manifesting any symptoms, patients relying on life support systems such as ventilators face an amplified risk of developing a serious infection. Once such an infection takes hold, the mortality rate among affected patients tragically climbs to approximately 45 percent, exacerbated by the fungus’s remarkable resistance to all major classes of antifungal medications. This widespread drug resistance presents formidable challenges for clinicians and unfortunately facilitates the pathogen’s persistent presence within the sterile environments of hospital wards.

The emergence of Candida auris as a formidable global health concern is shrouded in mystery, with its precise origins remaining elusive. First identified in 2008, the fungus has since been implicated in outbreaks across more than 40 nations, including the United Kingdom. Recognized by the World Health Organization as a critical priority fungal pathogen, Candida auris (also known by its scientific synonym Candidozyma auris) continues to represent a significant and growing threat to public health, with reported cases in the UK showing a consistent upward trend.

In a pivotal advancement, researchers affiliated with the University of Exeter have achieved a significant breakthrough by meticulously examining the intricate process of gene activation during Candida auris infection. This research represents the inaugural instance of such detailed genetic activity analysis conducted within a living organism, employing an innovative methodology centered on the use of fish larvae. The findings of this comprehensive study have been formally published in Communications Biology, a distinguished journal within the Nature portfolio, and were made possible through crucial financial support from Wellcome, the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the National Centre for Replacement, Reduction and Refinement (NC3Rs).

The researchers involved in this project posit that their findings could serve as a critical stepping stone in identifying a specific biological target for the development of novel antifungal therapies. Furthermore, there is potential for the repurposing of existing antifungal drugs, contingent upon the confirmation that this newly identified genetic behavior is indeed replicated during human infections.

This ambitious project was jointly spearheaded by Hugh Gifford, an NIHR Clinical Lecturer at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology (CMM), who also serves as a frontline clinician. Gifford articulated the profound impact of Candida auris, stating, "Since its emergence, Candida auris has inflicted significant damage wherever it has gained a foothold within hospital intensive care units. It poses a lethal threat to vulnerable patients, and health trusts have allocated substantial financial resources to the arduous task of its eradication. We believe our research may have uncovered a critical vulnerability, an ‘Achilles’ heel,’ within this deadly pathogen during active infection, and there is an urgent imperative for further research to ascertain whether we can discover and develop drugs that specifically target and exploit this weakness."

A primary impediment to understanding and combating Candida auris has been its remarkable ability to thrive at elevated temperatures. Coupled with its unusual tolerance for high salt concentrations, these characteristics have led some scientists to hypothesize that the fungus may have originated in tropical marine environments or within marine animal populations. These distinct biological traits have also presented significant challenges for conventional laboratory research models, making them less amenable to studying the fungus effectively.

To surmount these methodological hurdles, the University of Exeter team devised a pioneering infection model utilizing the Arabian killifish (Aphanius dispar). The eggs of this particular fish species possess the resilience to survive at temperatures mirroring human body temperature, thereby rendering them an exceptionally suitable model for observing fungal infection under conditions that closely approximate a genuine human illness.

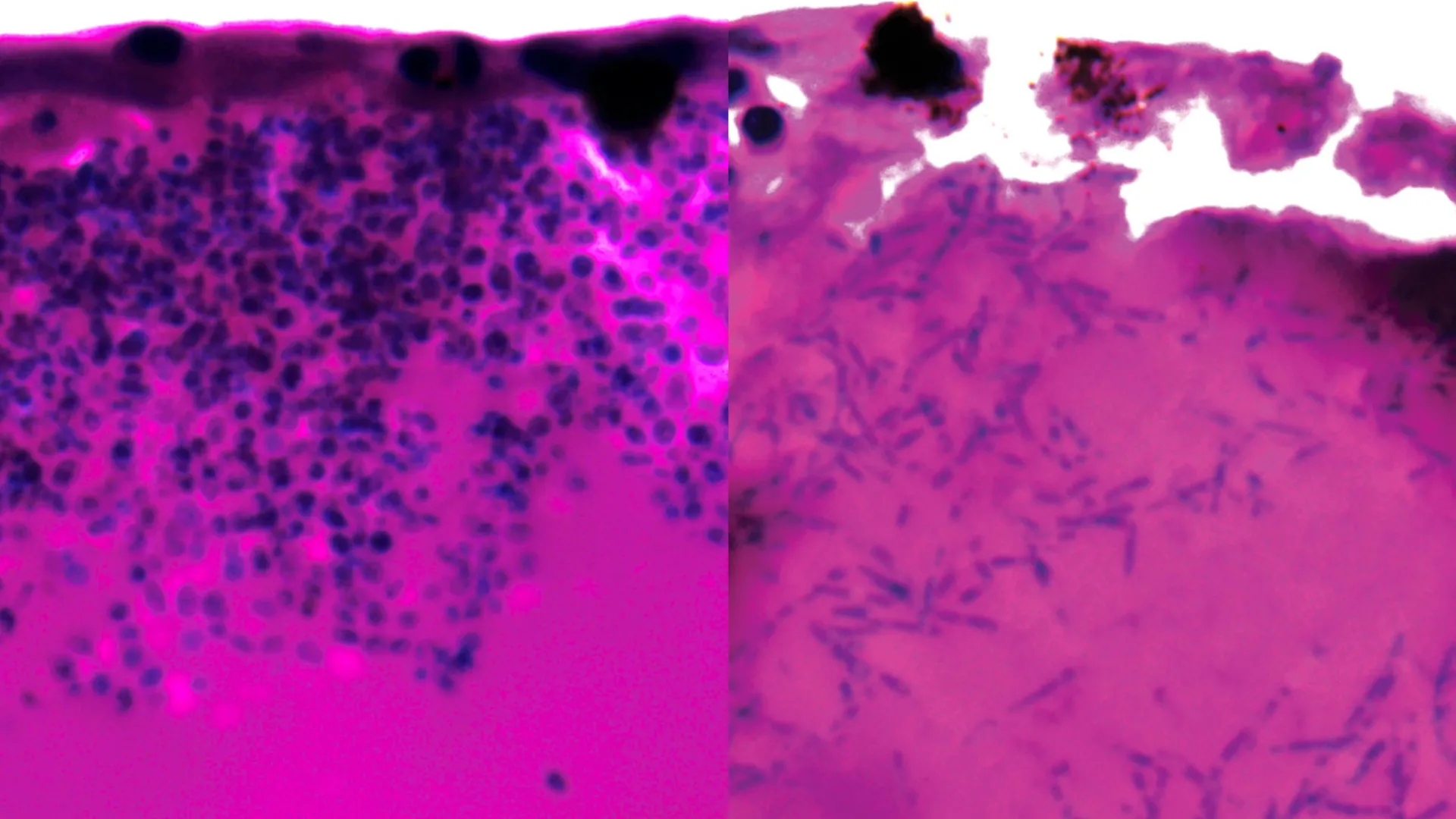

During their detailed experimental observations, the researchers documented that Candida auris exhibits a notable capacity for morphological transformation, adopting elongated filamentous structures. It is theorized that these filamentous forms may play a role in the fungus’s strategy for seeking out and acquiring essential nutrients during the course of an infection within a host organism.

A crucial aspect of the investigation involved a thorough analysis of gene expression patterns, specifically identifying which genes were either upregulated or downregulated during the infection process. This analysis was undertaken with the objective of pinpointing potential points of vulnerability. The study revealed that a number of genes that showed increased activity were responsible for the synthesis of nutrient transporters, specifically those involved in capturing iron-scavenging molecules and facilitating the subsequent transport of iron into the fungal cells. Given that iron is an indispensable element for the survival and proliferation of most living organisms, this iron acquisition pathway has emerged as a potentially critical weakness for Candida auris.

Dr. Rhys Farrer, a co-senior author of the study and a researcher at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, commented on the significance of these genetic insights, stating, "Up until this point, we possessed virtually no understanding of which genes are actively engaged during a host organism’s infection by this fungus. Our immediate next step is to determine whether this same genetic activity is observed during human infections. The discovery that genes involved in iron scavenging are activated provides compelling clues regarding the potential origins of Candida auris, perhaps an iron-deficient environment such as the sea. Crucially, it also presents us with a promising target for the development of both new and existing therapeutic agents."

Dr. Gifford, whose clinical practice as a resident physician in intensive care and respiratory medicine at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital provides him with firsthand experience of the devastating impact of such infections, underscored the profound clinical implications of these findings. He elaborated, "While there remain several important research stages to navigate, our discovery holds exciting promise for the future of treatment. We already possess pharmaceutical agents that are designed to inhibit iron scavenging mechanisms. Our task now is to rigorously investigate whether these existing drugs could be repurposed to effectively halt the pathogenic progression of Candida auris, thereby preventing it from causing fatalities in humans and averting the disruptive closures of hospital intensive care units."

The development of the Arabian killifish larvae model was facilitated by a project grant from the NC3Rs, representing a significant advancement in the search for alternatives to established animal models such as mice and zebrafish, which are commonly employed for studying host-pathogen interactions. Dr. Katie Bates, Head of Research Funding at the NC3Rs, lauded the research, stating, "This new publication beautifully illustrates the utility of this replacement model in studying Candida auris infection and has enabled us to gain unprecedented insights into the cellular and molecular events occurring within live infected hosts. This serves as a brilliant exemplar of how innovative alternative approaches can effectively overcome key limitations inherent in traditional animal studies." The peer-reviewed paper detailing these findings is titled ‘Xenosiderophore transporter gene expression and clade-specific filamentation in Candida auris killifish (Aphanius dispar) infection’ and is accessible in the esteemed journal Communications Biology.