A groundbreaking investigation has shed significant light on the intricate ways individuals on the autism spectrum and neurotypical individuals employ their facial musculature to convey internal emotional states, potentially illuminating the root causes of cross-group misunderstandings in affective signaling. This comprehensive study, spearheaded by researchers from the University of Birmingham and subsequently detailed in the esteemed journal Autism Research, represents a substantial leap forward in our comprehension of non-verbal emotional communication. The project meticulously cataloged a vast repository of facial movements associated with fundamental human emotions such as joy, sorrow, and ire, amassing an unprecedented dataset.

Employing sophisticated facial motion capture technology, the research team meticulously recorded and analyzed an astonishing volume of over 265 million distinct data points. This monumental effort has resulted in the establishment of what is arguably one of the most detailed and granular libraries of emotional facial kinematics ever compiled. The impetus behind such an ambitious undertaking was to move beyond anecdotal observations and establish a robust, data-driven understanding of how emotional expressions manifest differently, or similarly, across neurotypes. The researchers aimed to identify quantifiable differences that could be empirically verified, thereby offering a solid foundation for future research and intervention strategies.

The methodology employed in this pivotal study involved a carefully selected cohort of participants, comprising 25 adults diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and 26 neurotypical adults. Across this diverse group, a collective total of nearly 5,000 individual facial expressions were elicited and recorded. Participants were systematically prompted to manifest specific emotions – namely, anger, happiness, and sadness – under two distinct conditions. The first condition required them to synchronize their facial movements with accompanying auditory cues, while the second involved expressing these emotions organically during spontaneous speech. This dual-approach design was crucial for understanding how volitional control and spontaneous expression might differ in their execution.

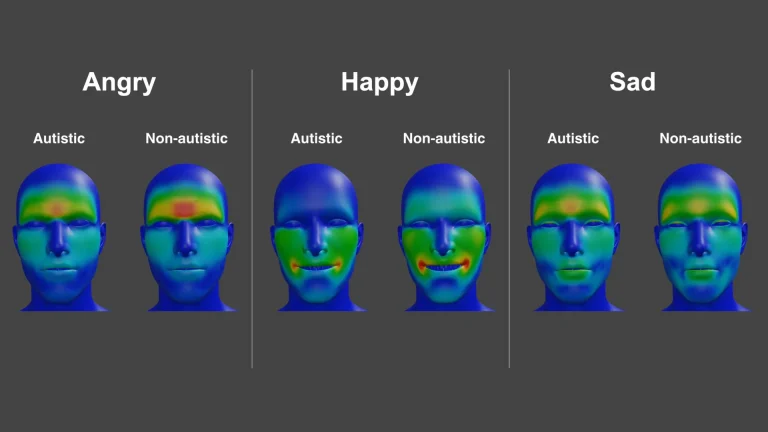

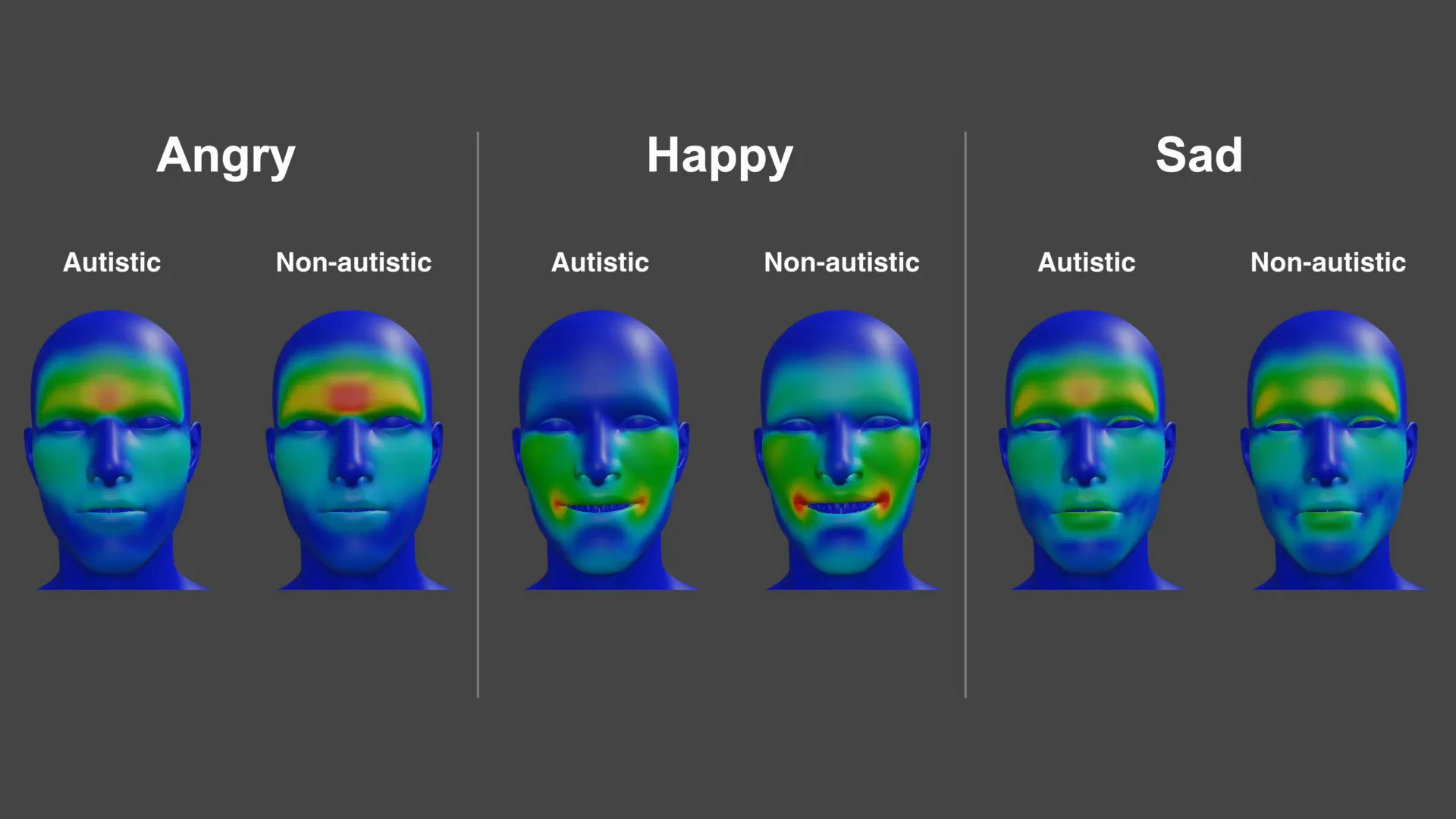

Upon rigorous analysis, distinct and discernible patterns of difference emerged between the two participant groups. Notably, individuals with autism not only exhibited variations in the execution of typical emotional expressions but also demonstrated a broader repertoire of unique facial configurations. The data revealed specific, recurring divergences. For instance, while neurotypical participants tended to exhibit a more consistent and predictable pattern of muscle activation for a given emotion, autistic participants sometimes displayed a wider range of subtle variations or alternative muscle engagements. This could manifest as a less pronounced or more generalized facial cue for a specific emotion, or conversely, a more complex interplay of muscle movements that, while conveying the intended emotion, deviated from the commonly recognized neurotypical archetype. The study meticulously mapped these variations, creating a detailed atlas of affective facial kinematics specific to each group.

A particularly insightful dimension of the research explored the significant role of alexithymia, a condition characterized by difficulties in identifying, describing, and processing one’s own emotions. Alexithymia is frequently observed in individuals with autism, often existing as a "sub-clinical" trait rather than a formal diagnosis in itself. The findings indicated a direct correlation between higher levels of alexithymia and a less defined or more ambiguous presentation of facial expressions for emotions like anger and happiness. Individuals experiencing greater alexithymic challenges tended to produce facial displays that were less overtly recognizable, making it more challenging for observers, regardless of neurotype, to accurately interpret the intended emotional valence. This suggests that the internal processing of emotion, and the subsequent outward manifestation, is deeply intertwined with an individual’s capacity for emotional self-awareness.

The implications of these observed discrepancies are profound, offering a compelling explanation for the persistent challenges in emotional understanding that often arise between autistic and neurotypical individuals. Dr. Connor Keating, the lead researcher on this project, who has since transitioned to the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford, elaborated on these findings. He emphasized that the observed differences extend beyond mere superficial appearances of facial expressions. According to Dr. Keating, "Our findings suggest autistic and non-autistic people differ not only in the appearance of facial expressions, but also in how smoothly these expressions are formed." This concept of "smoothness" refers to the fluidity and temporal progression of muscle movements during an expression. Mismatches in this dynamic aspect of facial communication, he posits, could be a significant contributing factor to why autistic individuals might struggle to accurately decode neurotypical expressions, and conversely, why neurotypical individuals may find it difficult to interpret the emotional cues from autistic individuals. This points to a potential disconnect in the very "grammar" of non-verbal emotional language.

Professor Jennifer Cook, the senior author of the study and a prominent figure at the University of Birmingham, stressed a critical perspective: these observed differences should not be construed as inherent deficits or impairments within the autistic population. Instead, she articulated a compelling analogy, suggesting that "Autistic and non-autistic people may express emotions in ways that are different but equally meaningful — almost like speaking different languages." This reframing is crucial. What has historically been interpreted as a communicative "difficulty" or "failure" on the part of autistic individuals might, in reality, represent a fundamental difference in communicative style. Professor Cook advocated for a paradigm shift, viewing these discrepancies not as a one-way challenge for autistic individuals, but rather as a "two-way challenge in understanding each other’s expressions." This perspective encourages a move towards mutual adaptation and a more nuanced appreciation of diverse communication styles. The research team is actively pursuing this line of inquiry, with future updates anticipated to further explore this model of reciprocal communicative complexity.

The foundational work underpinning this research was made possible through significant financial and institutional support. The project received crucial backing from the Medical Research Council (MRC) in the United Kingdom, a leading body for medical research funding. Furthermore, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme provided essential resources, underscoring the international recognition of the study’s importance and potential impact. This collaborative and well-funded approach has enabled the researchers to undertake a project of considerable scale and scientific rigor, laying the groundwork for a more inclusive and understanding approach to human social interaction. The detailed mapping of these expressive nuances offers a tangible pathway towards developing more effective communication strategies and fostering greater empathy between individuals with differing neurological profiles, ultimately aiming to bridge the gaps in affective understanding that can impact social relationships and well-being.