A groundbreaking advancement in neurotechnology, a remarkably compact brain implant, is poised to redefine human-computer interaction and unlock novel therapeutic avenues for a spectrum of neurological conditions. This innovative device establishes a minimally invasive, high-capacity pathway for communication directly with the brain, holding significant promise for managing conditions like epilepsy, assisting recovery from spinal cord injuries and strokes, and potentially restoring motor, speech, and visual functions. The core innovation lies in the device’s exceptionally small footprint combined with its remarkable data transmission capabilities.

Developed through a multidisciplinary collaboration involving researchers from Columbia University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania, this brain-computer interface (BCI) is engineered around a singular silicon chip. This chip functions as a wireless, high-bandwidth conduit, bridging the gap between neural activity and external computing systems. The system has been designated the Biological Interface System to Cortex, or BISC.

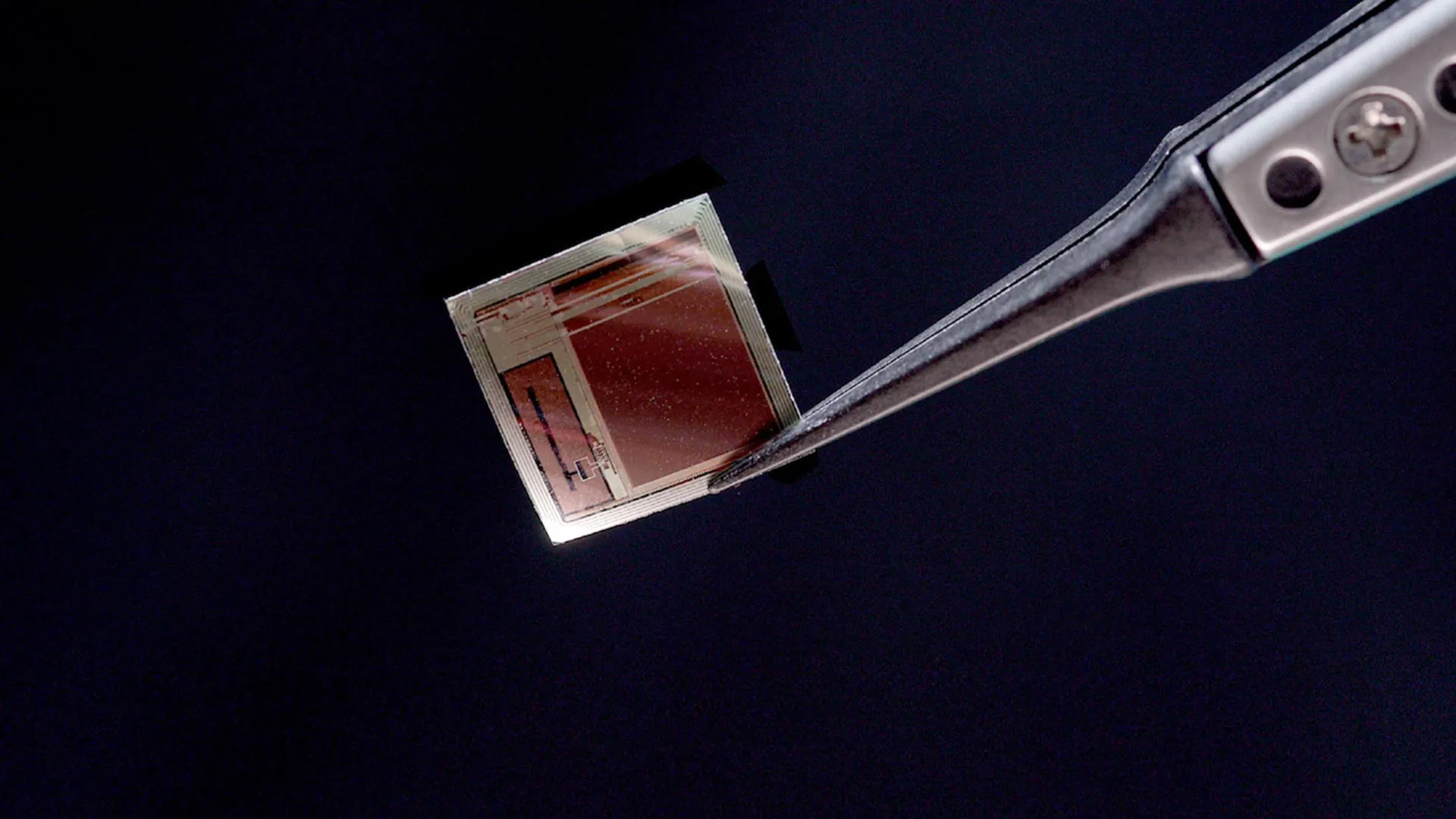

The architectural blueprint of BISC, detailed in a recent publication in Nature Electronics, encompasses the chip-level implant, a wearable external "relay station," and the sophisticated software infrastructure required for its operation. Traditional implantable systems often necessitate bulky electronic housings that occupy considerable internal volume. In stark contrast, the BISC implant is a single, integrated circuit chip of such extreme thinness that it can be delicately positioned between the brain and the skull, resting upon the cerebral cortex with minimal physical intrusion.

Spearheading the engineering efforts, Ken Shepard, a distinguished professor at Columbia University with appointments in electrical engineering, biomedical engineering, and neurological sciences, emphasized the transformative nature of this miniaturization. "Most implantable systems are built around a canister of electronics that occupies enormous volumes of space inside the body," Shepard explained. "Our implant is a single integrated circuit chip that is so thin that it can slide into the space between the brain and the skull, resting on the brain like a piece of wet tissue paper."

This technological leap is further amplified by the insights of Andreas S. Tolias, PhD, a senior and co-corresponding author from Stanford University’s Byers Eye Institute and co-founding director of the Enigma Project. Tolias’s profound expertise in training artificial intelligence systems with extensive neural recordings, including those gathered via BISC, proved instrumental in evaluating the implant’s capacity to interpret brain activity. "BISC turns the cortical surface into an effective portal, delivering high-bandwidth, minimally invasive read-write communication with AI and external devices," Tolias stated. "Its single-chip scalability paves the way for adaptive neuroprosthetics and brain-AI interfaces to treat many neuropsychiatric disorders, such as epilepsy."

The clinical dimension of this project was significantly advanced by Dr. Brett Youngerman, an assistant professor of neurological surgery at Columbia University and a neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Dr. Youngerman served as the primary clinical collaborator, highlighting the device’s potential impact. "This high-resolution, high-data-throughput device has the potential to revolutionize the management of neurological conditions from epilepsy to paralysis," he asserted. Youngerman, alongside Shepard and Dr. Catherine Schevon, an epilepsy neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, has recently secured a National Institutes of Health grant to investigate BISC’s application in treating drug-resistant epilepsy. "The key to effective brain-computer interface devices is to maximize the information flow to and from the brain, while making the device as minimally invasive in its surgical implantation as possible. BISC surpasses previous technology on both fronts," Youngerman added, underscoring the dual advancements in information transfer and surgical feasibility.

The advent of advanced semiconductor manufacturing has been the bedrock of this innovation, enabling the integration of computational power previously confined to room-sized systems into a device that fits within a remarkably small volume. "Semiconductor technology has made this possible, allowing the computing power of room-sized computers to now fit in your pocket," Shepard remarked. "We are now doing the same for medical implantables, allowing complex electronics to exist in the body while taking up almost no space."

The fundamental principle behind brain-computer interfaces involves decoding the intricate electrical signals that neurons use for communication. Existing medical-grade BCIs typically employ a modular approach, integrating multiple discrete microelectronic components such as amplifiers, data converters, and radio transmitters. These components are often housed within a comparatively large implanted canister, which requires either the removal of a portion of the skull or placement elsewhere in the body, with wires extending to the brain.

BISC represents a radical departure from this paradigm. The entire functional system is consolidated onto a single complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit. This chip has been meticulously thinned to a mere 50 micrometers and occupies less than one-thousandth the volume of conventional implants. With a total volume of approximately 3 cubic millimeters, this flexible chip is designed to conform to the curvature of the brain’s surface. This micro-electrocorticography (µECoG) device is equipped with an astonishing 65,536 electrodes, facilitating 1,024 recording channels and 16,384 stimulation channels. The utilization of established semiconductor industry manufacturing processes ensures the scalability of BISC for mass production.

Crucially, the BISC chip integrates a comprehensive suite of functionalities, including a radio transceiver, wireless power circuitry, digital control electronics, power management systems, data converters, and the analog components essential for both recording neural activity and delivering stimulation. The external relay station serves as the critical interface, providing both power and data communication through a bespoke ultrawideband radio link. This link achieves an impressive data throughput of 100 megabits per second, a rate that is at least 100 times greater than any other wireless BCI currently available. Operating akin to a standard Wi-Fi device, the relay station seamlessly connects the implant to any compatible computer.

BISC incorporates its own proprietary instruction set and a comprehensive software environment, effectively functioning as a dedicated computing system tailored for neural interfaces. The high-bandwidth recording capabilities demonstrated by this system enable brain signals to be processed by sophisticated machine-learning and deep-learning algorithms. These advanced algorithms can then interpret complex human intentions, perceptual experiences, and intricate brain states with unprecedented accuracy. "By integrating everything on one piece of silicon, we’ve shown how brain interfaces can become smaller, safer, and dramatically more powerful," Shepard reiterated.

The fabrication of the BISC implant leverages TSMC’s advanced 0.13-micrometer Bipolar-CMOS-DMOS (BCD) technology. This sophisticated manufacturing process integrates three distinct semiconductor technologies onto a single chip, enabling the efficient co-existence of digital logic (CMOS), high-current and high-voltage analog functions (bipolar and DMOS transistors), and power devices (DMOS). This synergistic integration is fundamental to achieving the exceptional performance characteristics of BISC.

Transitioning this advanced technology from the laboratory to clinical application is a primary objective. Shepard’s team has collaborated closely with Dr. Youngerman at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center to develop and refine surgical procedures for the safe implantation of the ultra-thin device in preclinical models. These efforts have successfully validated the device’s ability to produce high-quality, stable neural recordings. Initial short-term intraoperative studies involving human patients are currently in progress.

"These initial studies give us invaluable data about how the device performs in a real surgical setting," stated Youngerman. "The implants can be inserted through a minimally invasive incision in the skull and slid directly onto the surface of the brain in the subdural space. The paper-thin form factor and lack of brain-penetrating electrodes or wires tethering the implant to the skull minimize tissue reactivity and signal degradation over time." This approach significantly reduces potential complications and enhances the long-term viability of the implant.

Extensive preclinical research focusing on the motor and visual cortices was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Tolias and Bijan Pesaran, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania. Both are recognized leaders in the fields of computational and systems neuroscience, bringing valuable expertise to the project. "The extreme miniaturization by BISC is very exciting as a platform for new generations of implantable technologies that also interface with the brain with other modalities such as light and sound," Pesaran commented on the broad potential of the technology.

The development of BISC was supported by the Neural Engineering System Design program of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The project draws upon Columbia University’s extensive expertise in microelectronics, the advanced neuroscience programs at Stanford and Penn, and the renowned surgical capabilities of NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, creating a powerful synergy of knowledge and resources.

To accelerate the practical deployment of this technology, researchers from Columbia and Stanford have established Kampto Neurotech, a startup co-founded by Dr. Nanyu Zeng, an alumnus of Columbia’s electrical engineering program and a lead engineer on the BISC project. Kampto Neurotech is currently producing research-grade versions of the chip and actively seeking investment to facilitate the system’s eventual use in human patients. "This is a fundamentally different way of building BCI devices," Zeng affirmed. "In this way, BISC has technological capabilities that exceed those of competing devices by many orders of magnitude."

The accelerating pace of artificial intelligence development is increasingly converging with the potential of BCIs, not only for restoring lost neurological functions but also for exploring future applications that could enhance normal human capabilities through direct brain-to-computer communication. "By combining ultra-high resolution neural recording with fully wireless operation, and pairing that with advanced decoding and stimulation algorithms, we are moving toward a future where the brain and AI systems can interact seamlessly — not just for research, but for human benefit," Shepard concluded. "This could change how we treat brain disorders, how we interface with machines, and ultimately how humans engage with AI." This integrated approach promises a profound transformation in both medical treatment and human interaction with technology.