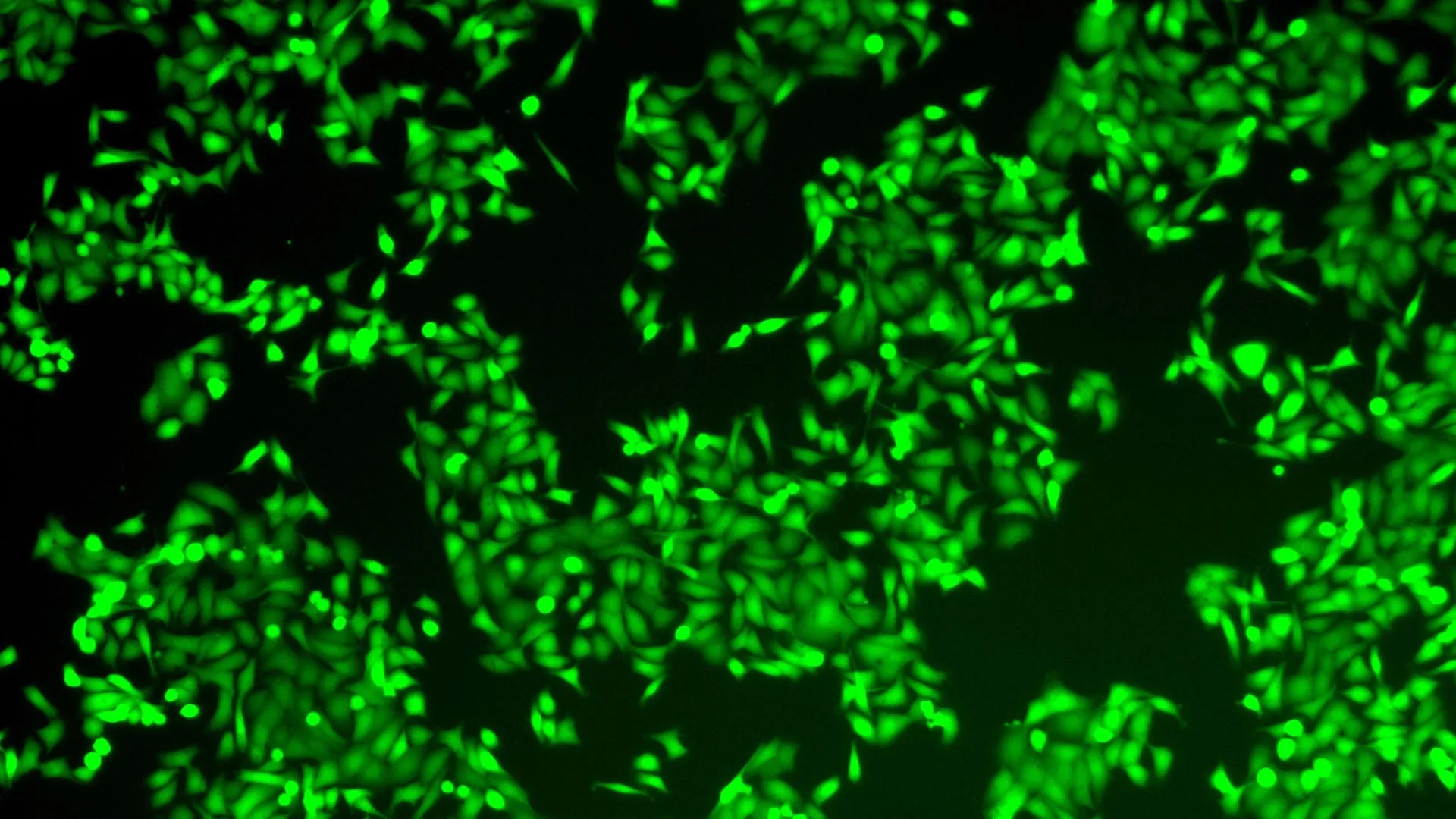

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) stands as one of the most formidable challenges in modern oncology, recognized not only as the most prevalent form of pancreatic malignancy but also as its deadliest variant. Its grim prognosis stems from a confluence of factors, including its typically late diagnosis, aggressive biological nature, and a distressing resistance to conventional therapeutic interventions. For decades, the landscape of PDAC treatment has largely revolved around strategies aimed at disrupting the activity of the KRAS gene, a frequently mutated oncogene found in a vast majority of these tumors. While KRAS-targeted therapies have shown promise in certain contexts, a significant proportion of PDAC tumors ultimately develop mechanisms to circumvent these treatments, highlighting an urgent, unmet medical need for novel, more effective therapeutic avenues. The ongoing quest for improved patient outcomes necessitates a deeper understanding of the fundamental molecular mechanisms that drive PDAC progression and the identification of previously unrecognized vulnerabilities.

In a significant stride towards this goal, pioneering research emanating from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has illuminated a previously unrecognized, self-reinforcing molecular circuit that acts as a critical engine for PDAC’s aggressive growth. This groundbreaking discovery not only offers an unprecedented insight into the disease’s underlying biology but also proposes an innovative therapeutic strategy to dismantle this oncogenic network. The investigation builds upon earlier work from Professor Adrian Krainer’s laboratory at CSHL, which in 2023 identified the protein SRSF1 as a crucial early instigator of PDAC tumor formation. This initial finding laid the groundwork for a more intricate exploration into how SRSF1 exerts its influence within the complex cellular environment of a developing tumor.

Delving further into the comprehensive datasets generated during that foundational study, a dedicated team, spearheaded by former CSHL graduate student Alexander Kral, uncovered that SRSF1 does not operate in isolation. Instead, it functions as a pivotal component within an intricate, three-part molecular alliance that collectively propels the cancer towards an increasingly aggressive phenotype. This revelation marks a critical shift in understanding, moving beyond individual oncogenes to recognize the power of interconnected biological systems in driving disease.

"Our working hypothesis was that specific cellular alterations, directly triggered by elevated levels of SRSF1, were instrumental in the accelerated tumor proliferation we were observing," explained Kral, elaborating on the research team’s initial approach. "Our focus narrowed down to a molecule we strongly suspected to be a key orchestrator in this process: Aurora kinase A (AURKA). What we subsequently uncovered was its integral role within a complex regulatory feedback loop. This circuit, far from being simplistic, encompasses not just AURKA and SRSF1, but also another highly significant oncogene, MYC." This statement underscores the iterative nature of scientific discovery, where initial findings lead to more profound, systemic understandings.

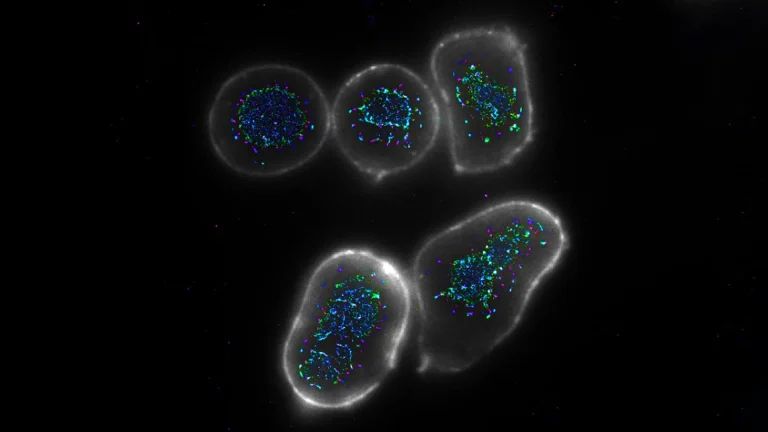

The newly identified molecular circuit represents a sophisticated feedback mechanism, where each component’s activity directly influences and amplifies the others, creating a sustained proliferative signal. At the core of this intricate system, SRSF1 exerts its control over AURKA through a fundamental biological process known as alternative splicing. Alternative splicing is a critical mechanism in gene expression, allowing a single gene to encode multiple protein variants, or "isoforms," each potentially possessing distinct functions. By modulating how the genetic blueprint of AURKA is processed, SRSF1 effectively dictates the production of specific AURKA isoforms, leading to a marked increase in its overall functional levels within the cancerous cell.

The elevated presence of AURKA, in turn, plays a crucial role in stabilizing and safeguarding the MYC protein. MYC is a powerful proto-oncogene, known for its extensive involvement in cell cycle progression, metabolism, and protein synthesis. Its stabilization by AURKA means that MYC can persist for longer durations and exert its oncogenic influence more robustly. Completing this dangerous feedback loop, MYC then actively promotes the increased production of SRSF1. This final step re-initiates the entire sequence, ensuring the continuous activation and amplification of the cancer-promoting signals. The cyclical nature of this interaction ensures a persistent, self-perpetuating drive towards uncontrolled cellular growth and heightened tumor aggression, making it a particularly challenging target for conventional single-agent therapies.

Professor Krainer emphasized the significance of this holistic discovery: "Individual fragments of this intricate circuit were previously known within the scientific community, but the comprehensive picture, the full operational mechanism, remained elusive until now. Once we meticulously pieced together the role of AURKA’s alternative splicing within this system, it immediately opened up exciting new avenues for exploring potential strategies to disrupt it." This sentiment highlights the immense value of integrative research, moving beyond isolated observations to reveal the systemic vulnerabilities that can be therapeutically exploited.

Armed with this newfound understanding of the complete oncogenic circuit, the research team embarked on developing a targeted intervention designed to dismantle it. Their strategy centered on interfering with the alternative splicing of AURKA. To achieve this, the CSHL scientists engineered an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) specifically tailored to modify the way AURKA’s genetic instructions are processed. ASOs are short, synthetic strands of nucleic acids designed to bind to specific RNA molecules, thereby modulating gene expression by either blocking protein production or altering RNA splicing.

The Krainer laboratory possesses extensive and unparalleled expertise in the development of ASO technology. This depth of experience is famously underscored by their pioneering work in creating Spinraza (nusinersen), which became the first-ever FDA-approved treatment for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Spinraza’s success revolutionized the treatment of a devastating neurological disorder, providing a tangible precedent for the transformative potential of ASO-based therapeutics. This historical success imbued the current research with both methodological rigor and a profound sense of purpose.

Based on their preliminary investigations and understanding of the circuit, the researchers initially anticipated that their newly engineered ASO would specifically block the aberrant splicing of AURKA. However, the experimental results in pancreatic cancer cells yielded an outcome far more profound and dramatic than initially predicted. The targeted ASO treatment did not merely inhibit AURKA splicing; it caused the entire self-reinforcing, cancer-driving circuit to catastrophically collapse. This systemic disruption led to a cascade of beneficial cellular events: tumor cells exhibited a significant loss of viability, and crucially, activated apoptosis, a highly regulated form of programmed cell death essential for eliminating damaged or unwanted cells.

Professor Krainer eloquently summarized the profound impact of this discovery, stating, "It’s akin to achieving multiple objectives with a single, precise action. SRSF1, AURKA, and MYC are all well-established oncogenes, each contributing significantly to the relentless progression of PDAC. By specifically targeting AURKA’s splicing with our ASO, we observed the concurrent and dramatic reduction in the levels of these other two critical molecules as well." This "three birds with one stone" effect signifies a major breakthrough, as it demonstrates the potential to simultaneously incapacitate multiple drivers of cancer aggression through a single, precisely targeted intervention, bypassing the need for complex combination therapies that often come with increased toxicity and logistical challenges.

While the current findings represent a monumental step forward in understanding and potentially treating PDAC, the researchers are quick to emphasize that any direct clinical application for patients remains a considerable distance in the future. The Krainer lab is actively engaged in refining and optimizing the ASO compound, an iterative process that involves enhancing its efficacy, specificity, and safety profile. This crucial foundational research is the bedrock upon which all major medical advancements are built. The journey from a laboratory discovery to a widely available patient treatment is arduous and protracted, typically involving extensive pre-clinical testing in various models, followed by rigorous multi-phase clinical trials in human subjects, and finally, navigating stringent regulatory approvals.

Professor Krainer underscores this critical perspective, drawing parallels to their previous success: "Major medical breakthroughs invariably originate from this kind of fundamental, rigorous research. Spinraza followed a strikingly similar developmental trajectory, progressing from initial laboratory insights to ultimately saving and improving thousands of lives globally." The hope is that with continued dedicated refinement and further validation, this pioneering work could one day culminate in the development of a groundbreaking, highly effective therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer—a disease that desperately needs new weapons in the fight against its devastating impact. This ongoing research not only promises to redefine the treatment landscape for PDAC but also exemplifies the enduring power of basic scientific inquiry to transform human health.