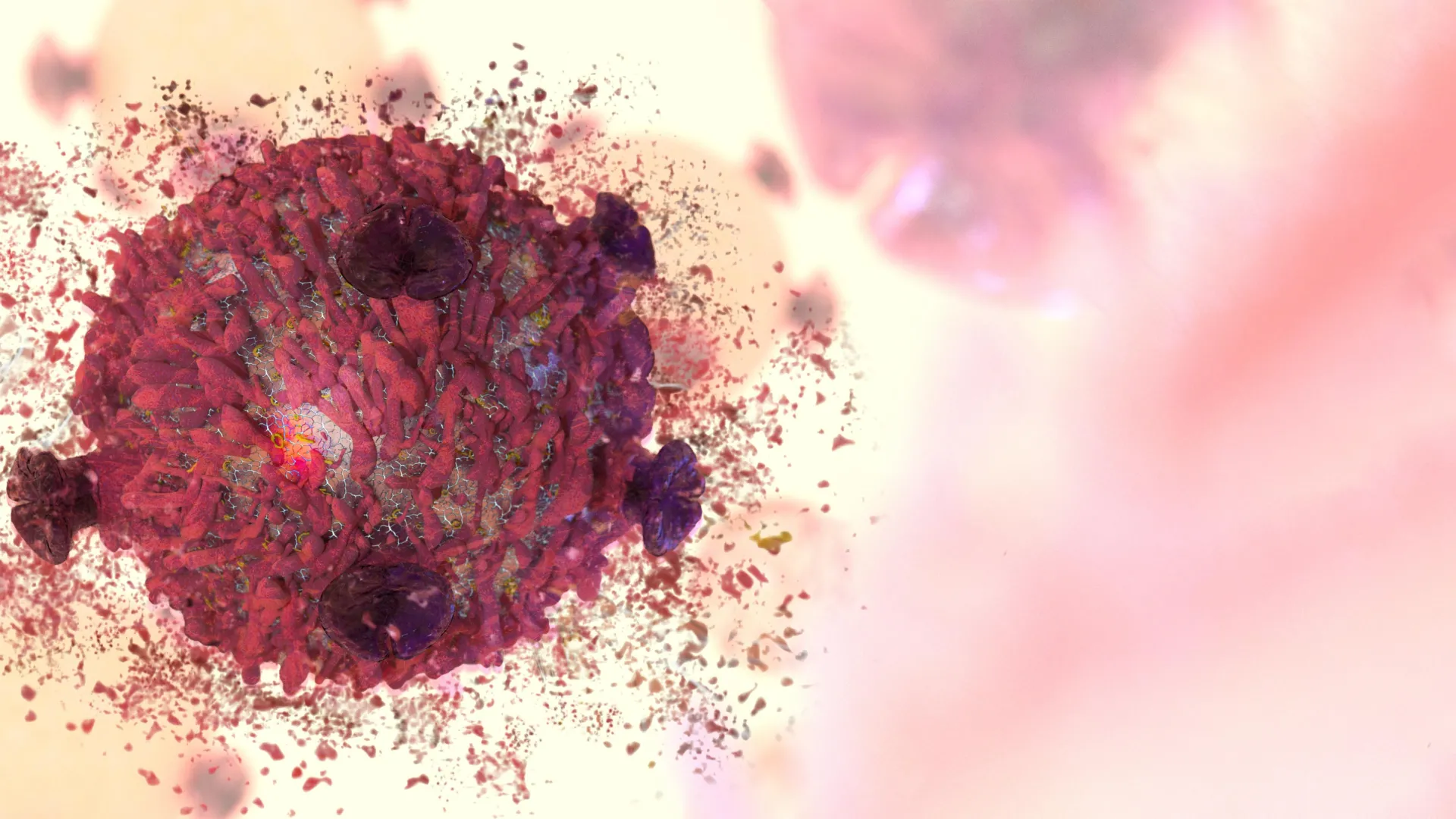

Researchers at RMIT University, in collaboration with international partners, have engineered microscopic metallic particles, termed nanodots, that exhibit a remarkable capacity to induce self-destruction in cancerous cells while leaving surrounding healthy tissue largely unaffected. This breakthrough, detailed in recent scientific findings, represents a novel frontier in the ongoing quest for more precise and less invasive cancer treatment modalities. The development hinges on the intrinsic properties of a metal-based compound, meticulously modified to exploit inherent vulnerabilities within malignant cells.

While the research remains in its nascent stages, confined thus far to laboratory settings with cultured cells, the implications are profound. The current investigations have not extended to animal models or human clinical trials, yet the foundational principles demonstrate a potent strategy for therapeutic intervention. The nanodots, synthesized from molybdenum oxide, a compound typically found in applications ranging from advanced electronics to robust industrial alloys, possess an unusual characteristic. Through subtle but critical alterations in their chemical composition, specifically the incorporation of minute quantities of hydrogen and ammonium, the researchers have engineered these particles to release reactive oxygen species.

These highly reactive oxygen molecules, often referred to as ROS, are potent agents of cellular damage. In healthy cells, the natural cellular defense mechanisms are robust enough to neutralize or repair the minor oxidative stress induced by these nanodots. However, cancer cells, by their very nature, exist in a state of heightened metabolic activity and elevated intrinsic stress. This pre-existing cellular fragility makes them disproportionately susceptible to further oxidative assault. The nanodots, therefore, act as a catalyst, pushing these already stressed cancer cells beyond their adaptive capacity, thereby triggering programmed cell death, a process known as apoptosis.

In rigorous laboratory assessments, these specifically engineered nanodots demonstrated a significant cytotoxic effect on human cervical cancer cells. Over a 24-hour period, the particles achieved a cancer cell kill rate three times greater than that observed in concurrently exposed healthy cells. A particularly noteworthy aspect of this development is that the nanodots’ efficacy does not rely on external stimuli such as light activation, a common requirement for many existing nanotechnological therapeutic approaches. This intrinsic reactivity streamlines the potential application and broadens the scope of where such treatments could be deployed.

Professor Jian Zhen Ou and Dr. Baoyue Zhang, the lead researchers from RMIT’s School of Engineering, elucidated the underlying mechanism. They explained that the precise manipulation of the molybdenum oxide’s electron management capabilities, achieved through the aforementioned chemical modifications, is key to the elevated production of reactive oxygen molecules. These molecules then instigate a cascade of events within the cancer cell, leading to the activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways. The body’s natural system for safely eliminating damaged or aberrant cells is thus harnessed to target malignant growths.

The potency of these nanodots’ chemical reactivity was further underscored in a separate experimental context. When exposed to a blue dye, the nanodots facilitated its breakdown by an impressive 90 percent within a mere 20 minutes, even in the complete absence of light. This observation highlights the robust nature of the oxidative stress they generate, independent of external energy sources.

The collaborative nature of this groundbreaking research is a testament to the global scientific community’s commitment to tackling complex health challenges. Beyond the core RMIT team, the study benefited from the expertise of Dr. Shwathy Ramesan from The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne, alongside contributions from researchers affiliated with Southeast University, Hong Kong Baptist University, and Xidian University in China. This multidisciplinary effort was further bolstered by the support of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs (COMBS), underscoring the foundational scientific infrastructure enabling such advancements.

The potential for this technology to revolutionize cancer treatment lies in its inherent selectivity. Many current therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy and radiation therapy, often inflict collateral damage on healthy tissues, leading to a host of debilitating side effects. The ability of these nanodots to preferentially target cancer cells by exploiting their unique physiological stress profile offers a pathway toward treatments that are not only more effective but also significantly gentler on the patient.

Furthermore, the choice of molybdenum oxide as the base material presents distinct advantages in terms of cost and accessibility. Unlike some advanced nanomaterials that rely on expensive or scarce noble metals such as gold or silver, molybdenum is a more abundant and less costly element. This factor could translate into more affordable and scalable manufacturing processes, potentially making advanced cancer therapies more accessible to a wider patient population.

The RMIT COMBS research team is actively pursuing the further development and validation of this promising technology. The immediate next steps on their agenda include a series of comprehensive investigations designed to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and potential clinical applications. These planned initiatives aim to rigorously assess the nanodots’ performance and safety profile in more complex biological systems, paving the way for future therapeutic breakthroughs. Organizations keen on exploring collaborative opportunities with the RMIT researchers in this transformative field are invited to make contact through the provided channels.