Emerging scientific inquiry is casting a shadow of doubt over the widely held perception that sugar substitutes, including aspartame, sucralose, and various sugar alcohols, represent a definitively healthier alternative to refined sugars like glucose. Consumers have increasingly gravitated towards these sugar-free options with the understandable aspiration of mitigating the health complications intrinsically linked to high sugar consumption. However, recent investigations are suggesting that this assumption may be fundamentally flawed, particularly concerning the sugar alcohol sorbitol.

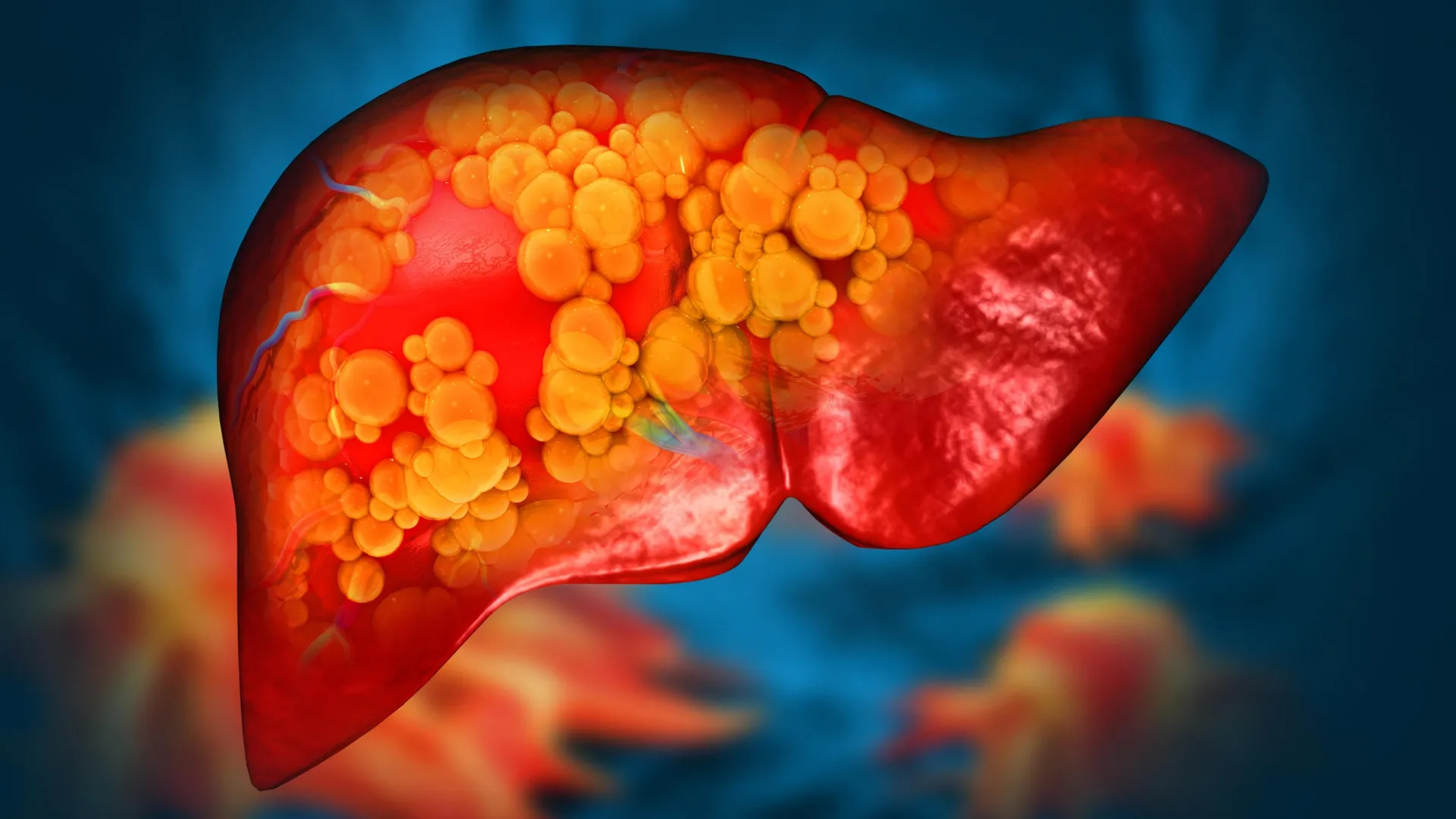

A groundbreaking study, published in the esteemed journal Science Signaling, is now prompting a significant re-evaluation of the safety profile of certain sugar substitutes. This research, spearheaded by Professor Gary Patti at Washington University in St. Louis, builds upon a robust foundation of prior investigations into the intricate ways fructose impacts the liver and other vital organs within the human body. Professor Patti, who holds distinguished positions as the Michael and Tana Powell Professor of Chemistry in Art & Sciences and Professor of Genetics and Medicine at WashU Medicine, has previously illuminated concerning pathways wherein fructose, metabolized by the liver, can be rerouted to potentially fuel the growth of cancerous cells. Furthermore, a substantial body of existing scientific literature has drawn a strong correlation between excessive fructose intake and the burgeoning epidemic of steatotic liver disease, a condition now affecting an estimated 30% of the global adult population.

The most surprising revelation from this latest research is the remarkably close biochemical kinship between sorbitol and fructose. Professor Patti articulates this connection by stating that sorbitol is essentially "one transformation away from fructose." This intimate relationship implies that sorbitol possesses the inherent capability to initiate metabolic responses within the body that are remarkably similar to those triggered by fructose itself, thereby posing analogous health concerns.

Through meticulously designed experiments utilizing zebrafish as a model organism, the research team demonstrated that sorbitol, a compound frequently incorporated into "low-calorie" confections, chewing gums, and naturally occurring in stone fruits, can indeed be synthesized endogenously. The study revealed that specific enzymes present within the intestinal tract possess the capacity to generate sorbitol. Once produced, this sorbitol is subsequently transported to the liver, where it undergoes conversion into fructose. This finding is particularly significant as it highlights an internal source of fructose precursors, independent of dietary intake.

Further unraveling the complex metabolic landscape, the researchers uncovered that the liver can receive fructose through a multitude of distinct biochemical pathways. The dominance of any particular pathway appears to be a dynamic interplay, influenced by several factors including the quantity of glucose and sorbitol an individual consumes, and crucially, the unique composition of the microbial community residing in their gut. This intricate interaction between diet and the gut microbiome underscores the personalized nature of metabolic processing.

While prior research on sorbitol metabolism predominantly focused on pathological conditions such as diabetes, where elevated blood glucose levels are known to precipitate excessive sorbitol production, Professor Patti’s work has illuminated a more nuanced reality. His findings indicate that sorbitol can be naturally generated within the gut environment following a meal, even in individuals who do not suffer from diabetes. The enzyme implicated in sorbitol synthesis exhibits a low affinity for glucose, meaning that a significant increase in glucose concentrations is typically required for its activation. This has historically led to its association with diabetic states. However, the zebrafish experiments provided compelling evidence that glucose levels within the intestine can indeed escalate to a sufficient threshold post-meal, thereby activating this sorbitol-producing pathway under normal physiological conditions. Professor Patti emphasizes this point, stating, "It can be produced in the body at significant levels."

The critical role of gut bacteria in managing sorbitol levels emerged as another pivotal discovery. Certain strains of Aeromonas bacteria possess the metabolic machinery to effectively break down sorbitol, converting it into innocuous bacterial byproducts. When these beneficial bacteria are present in sufficient numbers and are functioning optimally, the likelihood of sorbitol accumulating and causing adverse effects is significantly reduced. Conversely, Professor Patti explains, "However, if you don’t have the right bacteria, that’s when it becomes problematic. Because in those conditions, sorbitol doesn’t get degraded and as a result, it is passed on to the liver." This highlights the indispensable role of a healthy and diverse gut microbiome in maintaining metabolic homeostasis.

Upon reaching the liver, the untransformed sorbitol is converted into a fructose derivative. This biochemical transformation triggers significant concerns regarding the actual health benefits of alternative sweeteners, particularly for individuals managing diabetes and other metabolic disorders who often rely on products explicitly labeled as "sugar-free." The implication is that these individuals might be inadvertently increasing their fructose load through sorbitol-containing products, thereby undermining their health management strategies.

The point at which sorbitol intake becomes problematic is when the quantity consumed overwhelms the body’s natural detoxification mechanisms. At low concentrations, such as those encountered through the consumption of whole fruits, the resident gut bacteria are typically adept at metabolizing and clearing sorbitol. However, issues arise when the dietary influx of sorbitol, or the endogenous production triggered by high glucose levels, exceeds the capacity of these microbial allies. This overload can be precipitated by a high glucose diet, leading to increased sorbitol production, or by direct consumption of foods high in sorbitol. Even individuals with a robust population of beneficial gut bacteria may encounter challenges if their combined intake of glucose and sorbitol reaches excessively high levels, as even these microbes can be overwhelmed by the sheer volume. Professor Patti’s personal discovery of significant sorbitol content in his preferred protein bar underscores the ubiquitous presence of these sweeteners in everyday processed foods, making avoidance increasingly challenging.

The findings necessitate a fundamental re-evaluation of the long-standing assumption that sugar alcohols, also known as polyols, are inert substances that are simply eliminated from the body without consequence. While further research is imperative to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which gut bacteria degrade sorbitol, the current evidence strongly suggests that this assumption is no longer tenable. Professor Patti confirms the widespread distribution of sorbitol within the body, stating, "We do absolutely see that sorbitol given to animals ends up in tissues all over the body."

The overarching message conveyed by this body of research is that the simple act of substituting dietary sugar with artificial sweeteners is a far more complex endeavor than previously understood. As Professor Patti succinctly puts it, "there is no free lunch" when it comes to sugar alternatives. The intricate network of metabolic pathways within the human body means that many seemingly benign dietary choices can ultimately converge on liver dysfunction, a critical organ responsible for a multitude of essential physiological processes. This work received support from the National Institutes of Health under grants R35ES028365 (G.J.P.) and P30DK056341 (S.K.).