A significant breakthrough in understanding a notoriously resilient and life-threatening fungal pathogen, Candida auris, has been unveiled by researchers, offering a glimmer of hope against a microbe that has forced the closure of hospital intensive care units and posed a formidable challenge to public health. This discovery, which pinpoints a specific genetic mechanism crucial for the fungus’s survival during active infection, could pave the way for the development of entirely new therapeutic strategies or the repurposing of existing medications. The findings are particularly encouraging given the pathogen’s alarming resistance to all standard antifungal treatments and its capacity to spread rapidly within healthcare settings, making it an urgent global health concern.

Candida auris represents a unique threat, primarily to individuals with compromised immune systems or those requiring intensive medical support, such as mechanical ventilation. While the fungus can colonize the skin without causing overt illness, its invasive potential in vulnerable patients is exceedingly high, with mortality rates reaching approximately 45% among infected individuals. The fungus’s ability to thrive in the hospital environment, often persisting on surfaces and medical equipment, exacerbates the risk of outbreaks, leading to significant disruptions in healthcare services.

First identified in 2008, the precise origins of Candida auris remain an enigma, adding another layer of complexity to its control. Since its initial detection, the fungus has proliferated across more than 40 nations, including a notable presence in the United Kingdom, where reported cases have shown a consistent upward trend. This widespread dissemination has led the World Health Organization to classify Candida auris among its list of priority fungal pathogens, underscoring its status as a serious international health hazard.

To delve into the intricate processes of infection, a team at the University of Exeter embarked on a pioneering study, examining gene expression during Candida auris infection within a living biological model. This innovative approach, utilizing the larvae of the Arabian killifish (Aphanius dispar), marks the first instance of such genetic activity being investigated in a live host for this particular pathogen. The research, published in the journal Communications Biology, was generously supported by grants from Wellcome, the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the National Centre for Replacement, Reduction and Refinement (NC3Rs).

The implications of this research are far-reaching; by identifying the genetic pathways that the fungus employs to establish and maintain an infection, scientists may be able to pinpoint novel molecular targets for new antifungal drugs. Furthermore, if the identified genetic vulnerabilities are shared with human infections, existing medications that act on these pathways could potentially be repurposed, offering a faster route to clinical application.

Leading the research efforts, Hugh Gifford, an NIHR Clinical Lecturer at the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology (CMM), highlighted the devastating impact of Candida auris on hospital intensive care units. He noted the substantial financial investment and effort required by healthcare trusts to contain and eradicate outbreaks. Gifford expressed optimism that the study has uncovered a critical weakness, an "Achilles’ heel," within the pathogen during active infection, emphasizing the urgent need for further research to explore therapeutic interventions that can exploit this vulnerability.

A significant hurdle in studying Candida auris has been its remarkable resilience to elevated temperatures and its unusual tolerance for saline environments, leading some scientists to hypothesize its origins might lie in warm, marine ecosystems. These physiological characteristics have also presented challenges for conventional laboratory cultivation and experimental models.

The Exeter team ingeniously circumvented these limitations by employing Arabian killifish larvae. This species’ eggs possess the ability to withstand temperatures closely mirroring human body temperature, creating an ideal experimental environment to observe fungal infection dynamics under conditions that closely mimic human illness. This model offers a more physiologically relevant platform for studying the fungus’s behavior.

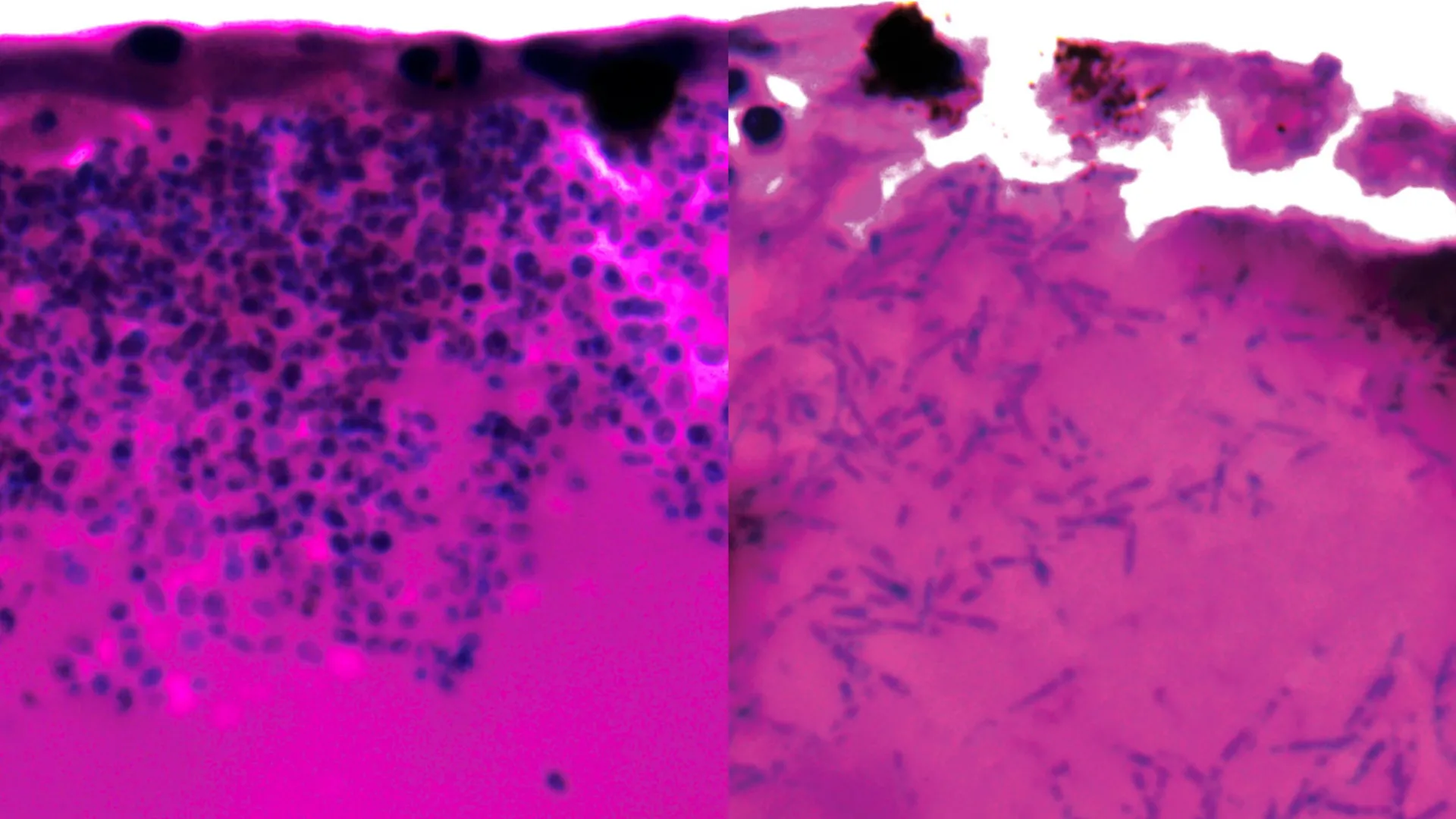

During their investigations, the researchers observed a key adaptation by Candida auris: the ability to transform its morphology by forming elongated, filamentous structures. These filaments are believed to facilitate nutrient acquisition as the fungus invades and colonizes host tissues.

Crucially, the team analyzed which genes were upregulated or downregulated during the infection process, seeking to identify points of weakness. Their analysis revealed a significant activation of genes responsible for producing specialized nutrient transporters. These transporters are critical for scavenging molecules that bind to iron and facilitating the subsequent uptake of iron into the fungal cells. Given iron’s indispensable role in fungal growth and survival, this iron-scavenging mechanism represents a potentially exploitable vulnerability.

Dr. Rhys Farrer, a co-senior author from the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, underscored the novelty of these findings, stating that prior to this study, there was a lack of understanding regarding the genetic activity of Candida auris within a living host. He stressed the importance of confirming whether this iron-scavenging behavior is also prevalent during human infections. The discovery of these genes being activated to acquire iron also provides intriguing clues about the fungus’s evolutionary origins, potentially pointing to iron-poor marine environments. More importantly, it offers a tangible target for the development of both novel and existing therapeutic agents.

From a clinical perspective, the findings hold substantial promise, as articulated by Dr. Gifford, who also serves as a physician specializing in intensive care and respiratory medicine at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital. While acknowledging that further research is essential, he described the discovery as an exciting prospect for future treatment paradigms. He pointed out that existing pharmaceutical compounds are already designed to inhibit iron-scavenging processes, suggesting a viable pathway for repurposing these drugs to combat Candida auris infections and prevent the disruption of critical hospital services.

The development of the Arabian killifish larvae model was instrumental in this research, supported by an NC3Rs project grant. This innovative model serves as an effective alternative to more traditional animal models, such as mice and zebrafish, which are commonly used to study host-pathogen interactions. Dr. Katie Bates, Head of Research Funding at NC3Rs, lauded the publication, emphasizing how this novel replacement model has facilitated unprecedented insights into the cellular and molecular events occurring within live infected hosts. She highlighted this work as a prime example of how innovative alternative approaches can effectively overcome the limitations inherent in conventional animal research.

The comprehensive findings of this study are detailed in the paper titled ‘Xenosiderophore transporter gene expression and clade-specific filamentation in Candida auris killifish (Aphanius dispar) infection,’ published in the peer-reviewed journal Communications Biology.