For an extended period, the prevailing tenet within neuroscience posited that mature neurons, once subjected to damage or demise, were incapable of regeneration. This deeply entrenched understanding has profoundly influenced the paradigms for comprehending and addressing neurological impairments stemming from trauma. Nevertheless, the observed phenomenon of individuals frequently regaining at least a partial restoration of lost faculties following such incidents presents a compelling conundrum: if neuronal regrowth is not a viable pathway, by what means does recovery manifest?

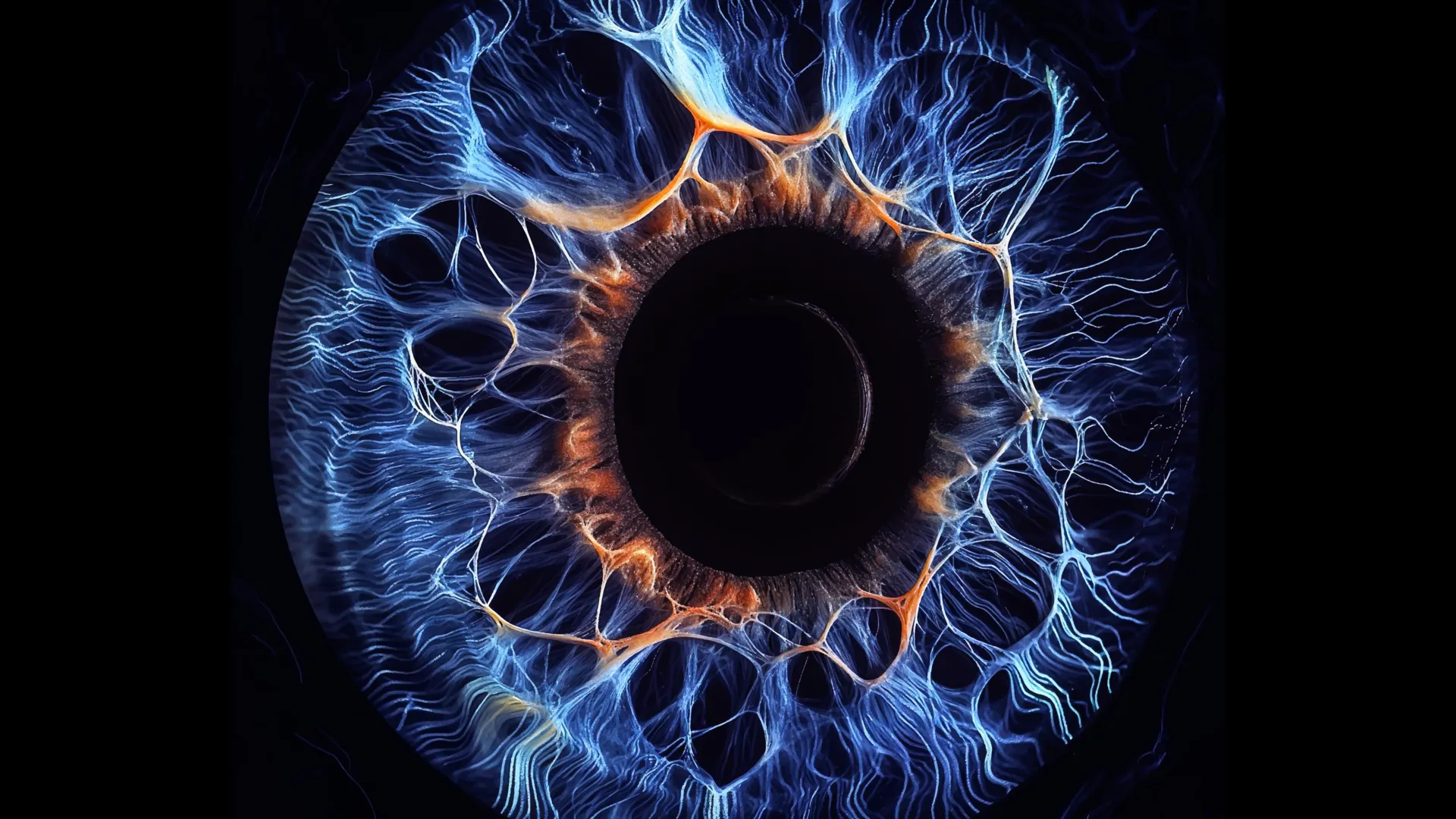

A recent publication in the esteemed journal JNeurosci offers a significant contribution to unraveling this intricate puzzle. Researchers, led by Athanasios Alexandris at Johns Hopkins University, embarked on a comprehensive investigation utilizing a murine model to meticulously examine the cellular and molecular events unfolding within the visual system subsequent to traumatic brain injury. The visual system, a complex network encompassing photoreceptor cells in the retina that transmit sensory information to the brain, is fundamental to the perception of sight in both animals and humans. Disruption to this delicate communication highway can precipitate a spectrum of visual disturbances.

Adaptation of Surviving Neural Elements Facilitates Ocular-Brain Pathway Reconstruction

In the aftermath of induced injury, the research team diligently monitored the integrity and functionality of the synaptic connections bridging the retina and the neuronal populations within the brain. Contrary to the expectation of widespread neurogenesis – the formation of new neurons – the observations revealed a distinct and remarkable adaptive strategy. Instead of new cells emerging, the neurons that successfully endured the traumatic insult initiated a process of profound cellular plasticity.

These resilient surviving neurons demonstrated an enhanced capacity to proliferate dendrites and axonal branches, effectively extending their reach and augmenting their connectivity with a broader array of neuronal targets in the brain than was initially established. This dynamic process, characterized by the extension of new synaptic boutons and collateral branches, is scientifically termed sprouting. It serves as a critical compensatory mechanism, stepping in to bridge the functional gaps created by the demise of other neuronal populations. Over a discernible period, the data indicated a significant recuperation in the density of connections between the retinal ganglion cells and their cerebral counterparts, ultimately approaching the baseline levels observed prior to the injurious event.

Crucially, the functional significance of these re-established neural pathways extended beyond mere structural reconstitution. Electrophysiological recordings and assessments of neural activity within the brain provided compelling evidence that these newly formed connections were not simply anatomical conduits. They were demonstrably functional, capable of efficiently transmitting neural signals and facilitating the re-initiation of visual processing. In tangible terms, this implies that the visual system, despite sustaining significant damage, regained a substantial degree of operational capacity.

Differential Recovery Trajectories Highlight Sex-Based Disparities in Visual System Resilience

A particularly striking revelation from this investigation was the identification of pronounced sex-specific differences in the recovery trajectory of the visual system. While male mice exhibited robust and efficient recovery, largely attributed to the aforementioned compensatory sprouting phenomenon, female mice displayed a markedly slower or, in some instances, incomplete repair process. The restoration of retinal-brain synaptic connections in the female cohort did not consistently revert to the pre-injury levels observed in their male counterparts.

The authors of the study propose that these findings underscore a fundamental divergence in the underlying mechanisms of neural recovery, with sex playing a pivotal role. As Dr. Alexandris articulated, the unexpected observation of sex differences resonates with existing clinical observations in human populations. He noted that women tend to report a higher incidence of persistent post-concussive symptoms and other lingering effects following brain injuries compared to men. Elucidating the precise molecular and cellular underpinnings of the observed branch sprouting, and crucially, identifying the factors that may impede or delay this restorative process in females, could pave the way for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies to enhance recovery from traumatic brain injuries and other forms of neurological insult.

The research consortium is committed to further exploring the biological underpinnings responsible for these observed sex-based discrepancies in neural repair. By delving deeper into the intricate biological factors that modulate the efficacy of neural recovery, the team aims to illuminate novel avenues for improving healing outcomes following a range of brain injuries, including concussions and other forms of physical trauma to the central nervous system. This ongoing research holds the potential to significantly advance our understanding of neuroplasticity and its therapeutic applications.