A decade-long scientific pursuit has culminated in a groundbreaking advancement: the development of a novel bioluminescent system that allows researchers to observe the intricate workings of the brain with unprecedented clarity and in real-time. This innovative approach shifts the paradigm from external light stimulation to intrinsic cellular illumination, enabling scientists to witness neural activity as it unfolds from within. The genesis of this transformative technology lies in a fundamental question posed by neuroscientists: "What if we could internally illuminate the brain?" This inquiry, championed by figures like Christopher Moore, a distinguished professor of brain science at Brown University, sought to overcome the inherent limitations of traditional methods. Existing techniques, such as fluorescence-based imaging, typically involve projecting external light onto brain tissue to measure or manipulate cellular activity. However, these methods often necessitate sophisticated and costly equipment, such as lasers and optical fibers, and can introduce experimental artifacts or even cellular damage due to prolonged light exposure. Furthermore, the process of fluorescence itself, where incoming light is re-emitted at a different wavelength, can be hampered by the inherent scattering and faint intrinsic glow of brain tissue, leading to diminished signal quality and a limited ability to probe deep within neural structures.

This ambitious vision to create self-illuminating neurons served as the foundational principle for the establishment of the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science in 2017. Bolstered by substantial financial backing from the National Science Foundation, the hub galvanized a multidisciplinary team of experts. This collaborative endeavor brought together leading minds, including Moore, who serves as the associate director of the Carney Institute, Diane Lipscombe, the institute’s director, Ute Hochgeschwender from Central Michigan University, and Nathan Shaner, affiliated with the University of California San Diego. The collective mission of this hub was to pioneer and disseminate novel neuroscience tools, imbuing nervous system cells with the capacity to both generate light and respond to its presence.

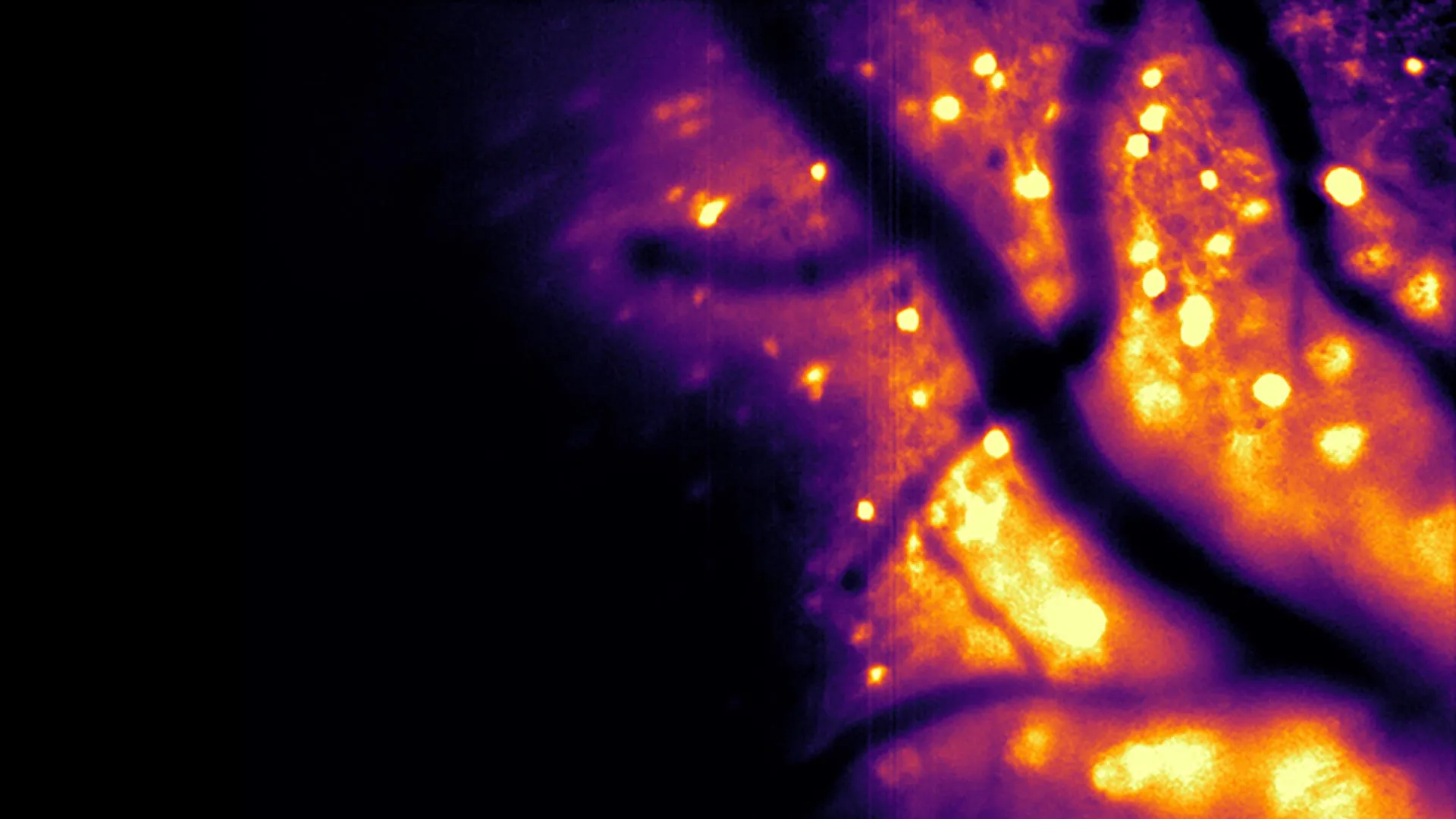

Central to this effort is the recent unveiling of a sophisticated bioluminescent imaging instrument detailed in a study published in the esteemed journal Nature Methods. This new tool, christened the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor, or "CaBLAM" for brevity, represents a significant leap forward in capturing neural dynamics. CaBLAM possesses the remarkable ability to record activity within individual cells and even more granular subcellular compartments at exceptionally high temporal resolutions. Its efficacy has been validated in model organisms such as mice and zebrafish, facilitating prolonged recording sessions that can extend for several hours without the need for any external light sources. Professor Moore lauded the ingenuity behind CaBLAM, attributing its molecular architecture to the expertise of Nathan Shaner, an associate professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at U.C. San Diego, describing the molecule as "truly amazing" and living up to its namesake.

The imperative to precisely track the activity of living brain cells is paramount for unraveling the complex mechanisms governing organismal function. Currently, the predominant methodology for this task relies on genetically encoded calcium indicators that leverage fluorescence. As Professor Moore elucidated, fluorescence operates on the principle of shining light onto a substance and observing the emission of light at a different wavelength. By engineering these fluorescent proteins to be sensitive to calcium ions, researchers can detect changes in light intensity or color, signaling the presence of calcium, which in turn indicates neuronal activity. While widely adopted, these fluorescence-based techniques are not without their considerable disadvantages. The sustained exposure to high-intensity external light required for excitation can inflict damage upon delicate neural tissue. Moreover, the continuous illumination can degrade the fluorescent molecules themselves, a phenomenon known as photobleaching, which diminishes their light-emitting capacity over time and thereby curtails the duration of experimental observations. The necessity of external light delivery systems, often involving lasers and optical fibers, also renders experiments more invasive and technically demanding.

In contrast, bioluminescent imaging offers a distinct set of advantages. This process involves the enzymatic breakdown of a specific small molecule, leading to the generation of light intrinsically within the cell. Consequently, no external light source is required, eliminating the risks of photobleaching and phototoxic damage to the neural environment. This inherent safety makes the approach particularly well-suited for studying the fragile architecture of the brain. Beyond its non-invasive nature, bioluminescence yields significantly clearer imaging results. Professor Shaner elaborated on this point, explaining that brain tissue naturally exhibits a faint glow when exposed to external light, creating a pervasive background noise that can obscure subtle signals. Furthermore, light scattering within the brain tissue further blurs incoming and outgoing signals, resulting in images that are dimmer, less defined, and challenging to interpret, especially when examining deeper neural regions. Since the brain does not naturally produce bioluminescence, engineered neurons that glow emit a distinct signal against a dark backdrop, minimizing interference. The cells effectively become their own light sources, akin to headlights, making their emitted light far easier to detect even as it navigates through scattered tissue. Professor Moore further emphasized that while the concept of using bioluminescence for brain research has been contemplated for decades, the challenge of achieving sufficient light intensity for detailed imaging had remained an insurmountable hurdle until now.

The scientific breakthrough that enabled the creation of CaBLAM stems from crucial insights into molecular engineering. The significance of the current research, as highlighted by Professor Moore, lies in the development of novel molecules that, for the first time, permit the visualization of individual cells firing independently. This capability is akin to employing a highly sensitive, specialized movie camera to record brain activity in real-time. With CaBLAM, researchers can now meticulously observe the behavior of a single neuron within a living organism, including the activity occurring within distinct parts of that cell. The study documented a continuous recording session lasting five hours, an achievement unattainable with conventional fluorescence-based methods. Professor Moore posited that bioluminescence facilitates the capture of entire complex processes, such as learning or intricate behaviors, with a reduced reliance on cumbersome hardware.

The CaBLAM project is an integral component of a broader initiative at the Bioluminescence Hub aimed at developing innovative methods for both observing and modulating brain activity. One compelling line of research involves engineering living cells to emit light signals that can be detected by neighboring cells, thereby enabling communication between neurons through light itself – a concept Professor Moore playfully terms "rewiring the brain with light." The team is also advancing techniques that harness calcium ions to regulate cellular functions. As these diverse projects progressed, the researchers recognized a common, critical requirement: the need for increasingly bright and efficient calcium sensors. This need has emerged as a central focus of the hub’s ongoing investigations. Professor Moore underscored the hub’s commitment to ensuring that, as an organization dedicated to pushing the frontiers of neuroscience, it develops and provides the essential foundational components for future discoveries.

The potential applications of CaBLAM extend far beyond the realm of neuroscience, according to Professor Moore. He envisions its utility in studying cellular activity across various other parts of the body, opening up an entirely new spectrum of possibilities for understanding physiological processes. The technology could enable the simultaneous tracking of activity in multiple bodily regions. This significant advancement underscores the profound impact of collaborative research, with the CaBLAM project benefiting from the contributions of at least 34 scientists from partner institutions including Brown University, Central Michigan University, U.C. San Diego, the University of California Los Angeles, and New York University. The groundbreaking work was made possible through substantial funding from prestigious organizations such as the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.