Groundbreaking research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has unveiled a critical mechanistic link between prolonged consumption of high-fat diets and an elevated risk of liver cancer. The study illuminates how dietary fat fundamentally alters the very nature of liver cells, setting a dangerous precedent that significantly accelerates the potential for malignant transformation. This new understanding goes beyond merely associating diet with disease, pinpointing the specific cellular and molecular pathways that render the liver acutely vulnerable.

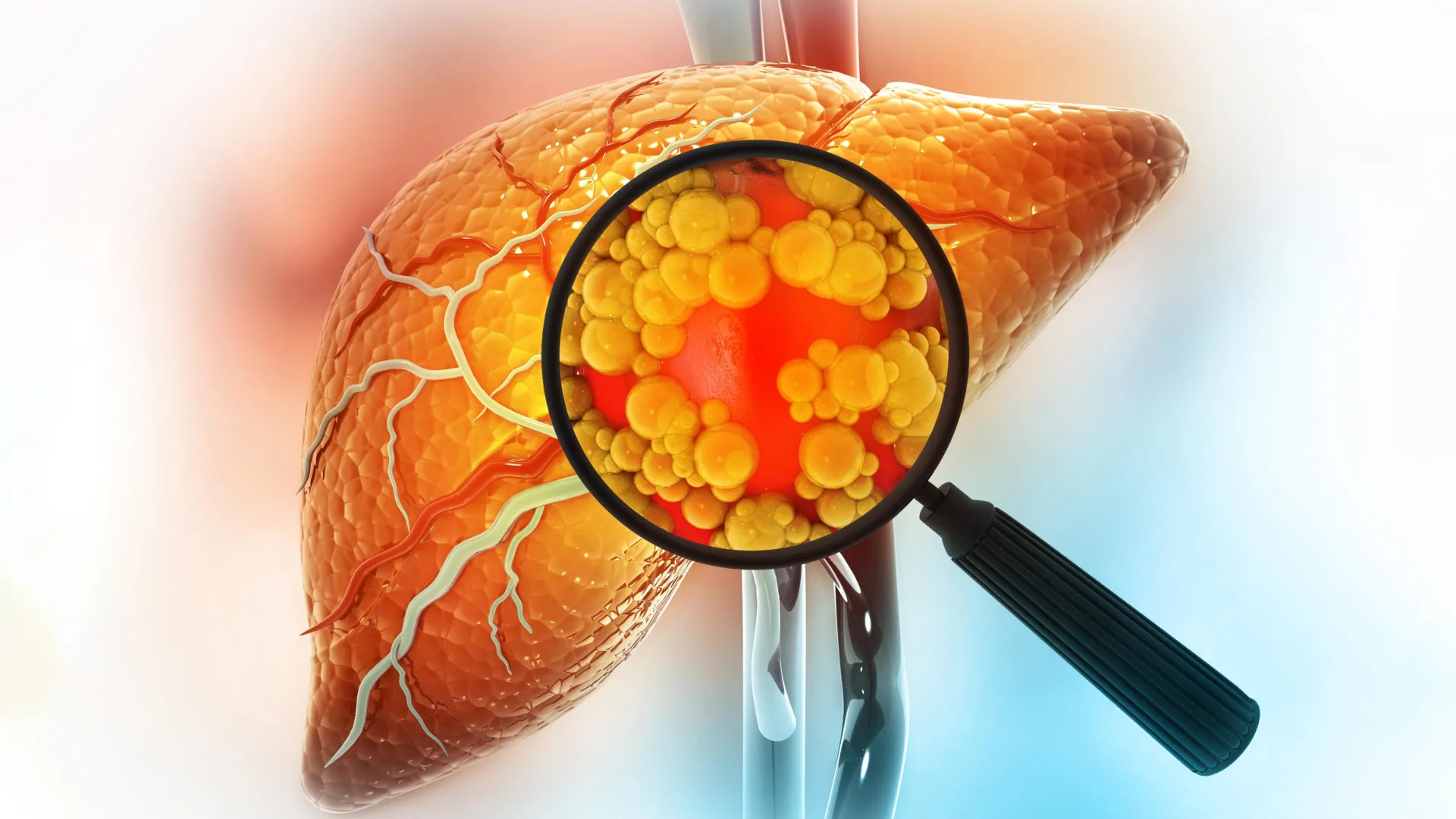

The liver, a vital organ responsible for myriad metabolic processes, including detoxification and nutrient processing, faces immense stress when subjected to a chronic influx of high-fat nutrients. This persistent dietary challenge, the researchers discovered, compels mature liver cells, known as hepatocytes, to undergo a profound phenotypic shift. Instead of maintaining their highly specialized functions, these cells regress into a more rudimentary, stem-cell-like state. This cellular plasticity, while initially a survival mechanism to cope with metabolic overload, paradoxically lays the groundwork for future oncogenesis.

"When cells are continually forced to contend with an environmental stressor, such as an persistently high-fat dietary regimen, they implement strategies to ensure their immediate survival," explained Alex K. Shalek, a key senior author of the study and director of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Sciences (IMES) at MIT. "However, these adaptive measures come with an inherent risk of escalating susceptibility to tumor formation over the long term." This statement underscores the precarious balance between cellular resilience and the potential for pathological progression.

The scientific team further advanced this understanding by identifying several crucial transcription factors – proteins that regulate gene expression – which appear to orchestrate this cellular metamorphosis. These factors represent promising new avenues for therapeutic intervention, potentially serving as targets for pharmaceutical agents aimed at mitigating the risk of tumor development in individuals predisposed to, or already experiencing, liver pathology due to dietary habits. The findings, published in the esteemed journal Cell on December 22, represent a significant stride in deciphering the complex interplay between diet, cellular biology, and cancer. The collaborative effort was led by Shalek, alongside Ömer Yilmaz, an MIT associate professor of biology, and Wolfram Goessling, co-director of the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology, with significant contributions from co-first authors Constantine Tzouanas, Jessica Shay, and Marc Sherman.

The journey from a high-fat diet to liver cancer is often insidious, marked by a progression through several stages of liver disease. Chronic exposure to excessive dietary fat initiates a cascade of events, leading to inflammation and the accumulation of lipids within liver cells, a condition medically termed steatotic liver disease (formerly known as fatty liver disease). This condition, which can also be triggered by other long-term metabolic stressors like significant alcohol consumption, can advance to more severe forms such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), characterized by inflammation and cell damage. Without intervention, NASH can progress to fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis (irreversible scarring that impairs liver function), liver failure, and ultimately, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of primary liver cancer.

The MIT investigation sought to unravel the intricate molecular responses of liver cells when confronted with a high-fat diet. The researchers meticulously focused on deciphering which genes became more or less active as the metabolic stress intensified, providing a granular view of cellular adaptation. To achieve this, the team employed a sophisticated experimental model, feeding mice a carefully controlled high-fat diet. Crucially, they utilized single-cell RNA-sequencing, an advanced technique that allows scientists to analyze gene activity within individual cells rather than bulk tissue. This methodological precision enabled them to track dynamic changes in gene expression as the animals progressed through the different stages of liver disease, from initial inflammation to tissue scarring and, ultimately, cancerous transformation.

Early in the disease trajectory, the hepatocytes began to activate a distinct set of genes designed to enhance cellular survival under adverse conditions. These included genes that actively suppress programmed cell death (apoptosis) and promote sustained cellular growth. Concurrently, genes essential for the liver’s normal physiological operations, such as those involved in metabolic regulation and protein secretion, gradually diminished in activity. This observed shift paints a clear picture of cellular prioritization. "This essentially appears to be a compensatory mechanism, where the individual cell prioritizes its own survival within a challenging environment, even if it comes at the expense of the collective functional integrity of the tissue," observed Constantine Tzouanas, an MIT graduate student and co-first author of the paper.

Some of these genetic reconfigurations occurred with remarkable speed, while others manifested more gradually over time. For instance, the reduction in the production of metabolic enzymes was a slower, more protracted process. By the conclusion of the study, a significant majority of the mice maintained on the high-fat diet had developed liver cancer, starkly illustrating the profound carcinogenic potential of such dietary patterns.

The research unequivocally demonstrated that when liver cells exist in this less mature, more primitive state, their susceptibility to cancerous transformation significantly escalates should a damaging mutation subsequently arise. This finding is central to understanding the "head start" phenomenon. "These cells have already activated many of the genetic pathways they would eventually need to become cancerous," Tzouanas elaborated. "They have already diverged from their mature identity, which would otherwise constrain their capacity to proliferate uncontrollably. Consequently, once such a cell acquires an oncogenic mutation, its progression towards full-blown cancer is dramatically expedited, as it has already acquired some fundamental hallmarks of malignancy."

The study also brought to light several key genes that play a coordinating role in this reversion to an immature cellular state. Intriguingly, during the course of this research, a pharmaceutical agent targeting one of these identified genes – the thyroid hormone receptor – received regulatory approval for treating a severe form of steatotic liver disease known as MASH fibrosis. Furthermore, another enzyme identified in the study, HMGCS2, is currently the subject of clinical trials for steatotic liver disease, suggesting the immediate translational relevance of these discoveries. Another particularly compelling target unearthed by the research is a transcription factor named SOX4. This factor is typically active during embryonic development and in a limited number of adult tissues, notably not the healthy adult liver, making its observed activation in liver cells under high-fat stress especially noteworthy and a prime candidate for targeted therapies.

To ascertain the broader applicability of their findings, the researchers meticulously investigated whether similar cellular patterns manifest in human liver disease. They analyzed liver tissue samples obtained from patients at various stages of liver pathology, including individuals who had not yet progressed to cancer. The human data strikingly corroborated the observations in the mouse models. Over time, genes vital for normal liver function exhibited a decline in expression, while genes associated with immature cellular states showed a marked increase. The study further revealed that these specific gene expression patterns could serve as powerful prognostic indicators, predicting patient survival outcomes. "Patients exhibiting higher expression of these pro-cell-survival genes, which are upregulated in response to a high-fat diet, demonstrated shorter survival durations after tumor development," Tzouanas confirmed. "Conversely, if a patient displayed lower expression of genes that support the liver’s normal physiological functions, their survival time also tended to be reduced."

While the mouse models developed cancer within approximately one year under the experimental conditions, the researchers estimate that this same process in human beings likely unfolds over a considerably longer timeframe, potentially spanning two decades or more. The precise timeline can fluctuate significantly based on individual dietary habits and other contributing risk factors, including chronic alcohol consumption and viral infections, both of which can independently or synergistically propel liver cells towards this vulnerable, immature state.

A critical question arising from these findings is whether the cellular damage induced by high-fat diets can be reversed. The research team is now poised to embark on further investigations to explore this crucial aspect. Future studies are planned to assess whether a return to a healthier, balanced diet or the judicious use of weight-loss medications, such as GLP-1 agonists, can effectively restore normal liver cell behavior and prevent or reverse this pathological cellular reprogramming. They also intend to delve deeper into the identified transcription factors, such as SOX4, to rigorously evaluate their potential as effective pharmacological targets for preventing the progression of damaged liver tissue to overt cancer.

"We now possess an array of novel molecular targets and a significantly enhanced comprehension of the underlying biological mechanisms at play," Shalek concluded. "This expanded knowledge base offers us unprecedented new perspectives and potential strategies to improve clinical outcomes for patients afflicted with liver disease and, importantly, to prevent the devastating onset of liver cancer." The research received partial funding from prestigious organizations including a Fannie and John Hertz Foundation Fellowship, a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health, and the MIT Stem Cell Initiative through Foundation MIT, underscoring the collaborative and foundational nature of this pivotal scientific endeavor.