A groundbreaking investigation, detailed in the latest issue of Science Bulletin, has illuminated a novel and surprisingly efficient mechanism by which viruses can propagate through host tissues, a discovery that fundamentally redefines our understanding of viral pathogenesis. Researchers affiliated with the Peking University Health Science Center and the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute have identified a previously uncharacterized cellular export system that viruses can hijack to achieve significantly accelerated and more aggressive infection cycles. This finding introduces a new dimension to virology, suggesting that the innate migratory functions of cells can be repurposed by pathogens to enhance their transmissibility and virulence.

The core of this revelation lies in the observation of how infected cells, specifically when engaging in migratory activities, package viral components. In cells infected with the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a well-studied model pathogen, the genetic material and essential viral proteins are not merely released haphazardly into the extracellular environment. Instead, these critical viral constituents are actively incorporated into structures known as migrasomes. Migrasomes are cellular vesicles that are transiently formed and released by cells, particularly those that are in the process of moving or migrating within an organism. This specific association means that viral propagation is intimately linked to cellular motility, suggesting a sophisticated exploitation of cellular biology by the virus.

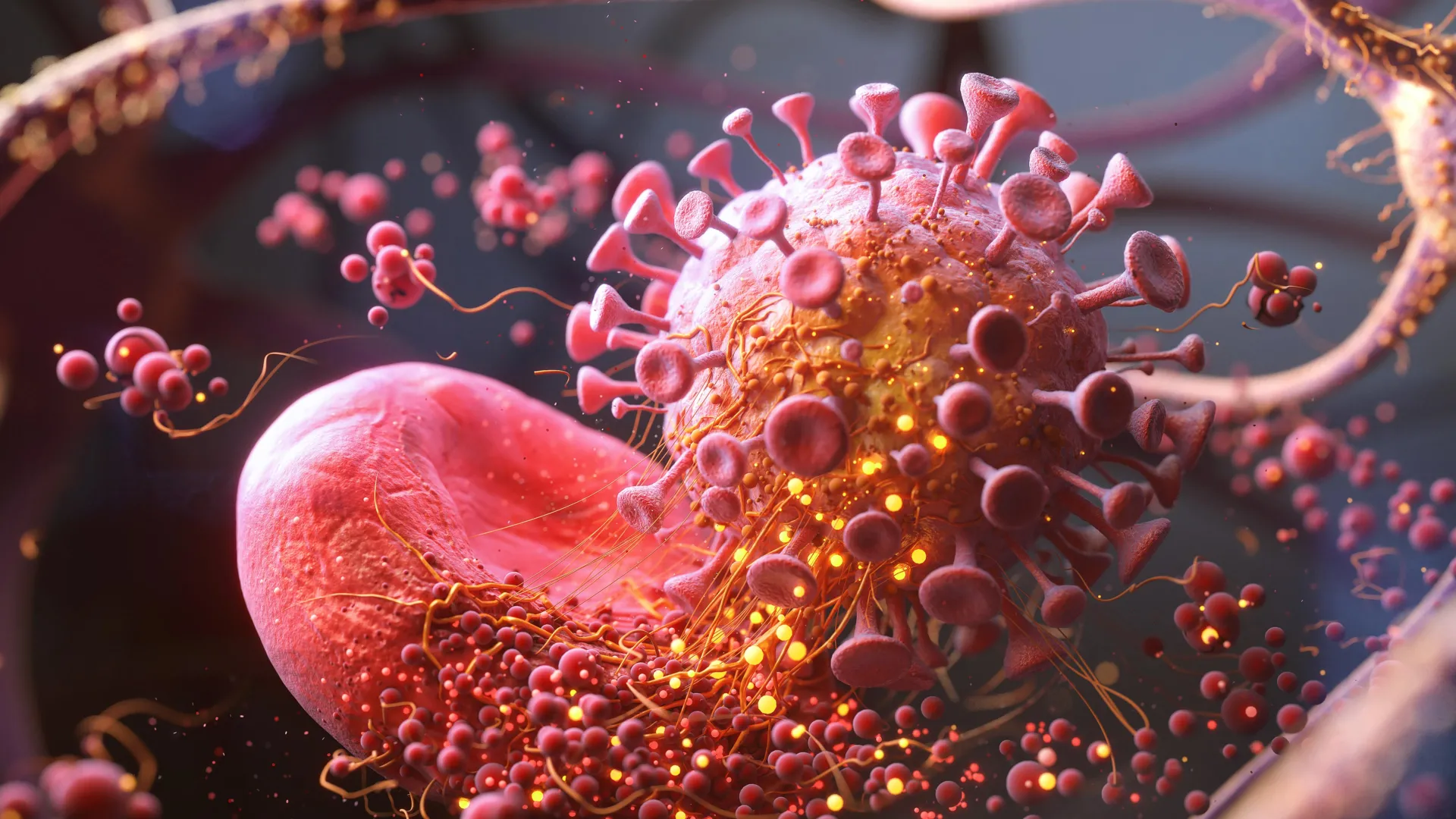

Further scrutiny of these migrasomes revealed a remarkable transformation: some of them were observed to contain viral nucleic acids within their internal structure, while simultaneously displaying the viral surface protein VSV-G on their exterior. These composite entities, comprising both viral and cellular material, have been aptly christened "Migrions" by the research team. Migrions are not simply free-floating viral particles; they represent a distinct class of virus-like packages, born from the confluence of viral replication and cellular migratory processes. Their formation signifies a departure from conventional viral release mechanisms, where individual virions are shed from an infected cell.

The implications of viral transmission via Migrions are profound, particularly concerning the speed and efficacy of subsequent infections. When viruses utilize this Migrion pathway, they demonstrate a demonstrably faster rate of replication within newly infected host cells. This accelerated growth is attributed to the fact that each Migrion delivers a concentrated payload, containing multiple copies of the viral genome simultaneously. This immediate and parallel introduction of viral genetic material into the target cell allows for replication to commence almost instantaneously, bypassing the initial lag phase often associated with single-particle infections. This rapid initiation of replication contributes significantly to the heightened pathogenicity observed with Migrion-mediated spread.

Beyond their efficiency in delivering single viral species, Migrions exhibit an even more intriguing capability: they can serve as carriers for multiple types of viruses concurrently. This capacity for co-transmission of different viral agents sets Migrions apart from other known extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated viral spread mechanisms, which typically involve a more specialized and less promiscuous cargo loading. The ability of a single Migrion to harbor and deliver distinct viral genomes opens up complex scenarios for viral evolution and the emergence of novel co-infections, potentially leading to more complicated and severe disease manifestations. This poly-viral carriage represents a significant departure from established models of viral intercellular communication.

The process by which Migrions infect new cells is also noteworthy for its adaptability. Upon reaching a target cell, Migrions gain entry through endocytosis, a common cellular uptake mechanism, without the need to bind to specific cell surface receptors that are often exploited by conventional viruses. Once internalized within an endosome, the acidic environment typically found within these cellular compartments triggers a conformational change in the VSV-G protein embedded in the Migrion’s outer membrane. This activation facilitates the fusion of the Migrion’s membrane with the endosomal membrane. This critical fusion event liberates the viral contents into the cytoplasm, thereby initiating the infection cascade and paving the way for viral replication. This receptor-independent entry mechanism enhances the Migrion’s ability to infect a broader range of cell types.

The pathogenic potential of Migrion-mediated viral spread has been starkly illustrated through experiments conducted in animal models. Studies utilizing mice revealed that infection initiated by Migrions is substantially more infectious and leads to significantly more severe disease outcomes compared to infections initiated by equivalent numbers of free virus particles. Animals inoculated with Migrion-containing preparations developed much more aggressive pathologies, including severe inflammation and damage to vital organs such as the lungs and brain. The observed symptoms included encephalitis, a dangerous inflammation of the brain, and a markedly higher mortality rate, underscoring the amplified virulence associated with this newly discovered transmission route.

This discovery necessitates a fundamental reassessment of how viruses navigate and disseminate within a host organism. The researchers propose that the Migrion, characterized as a hybrid structure formed through the intricate interplay between viral components and cellular migrasomes, represents an entirely novel paradigm for viral transmission between cells. By directly tethering viral propagation to the inherent migratory capabilities of host cells, this mechanism challenges long-held assumptions about the passive nature of viral spread through surrounding tissues. Instead, viruses can actively leverage the body’s own sophisticated cellular locomotion machinery to achieve rapid and systemic distribution. This migration-dependent strategy offers a compelling new perspective on viral dissemination dynamics and provides a potential explanation for the remarkably swift escalation observed in certain infectious diseases, particularly those that involve extensive tissue infiltration. The implications for antiviral therapies and disease control strategies are substantial, as interventions may need to target not only viral replication but also these novel cellular export and transport mechanisms.