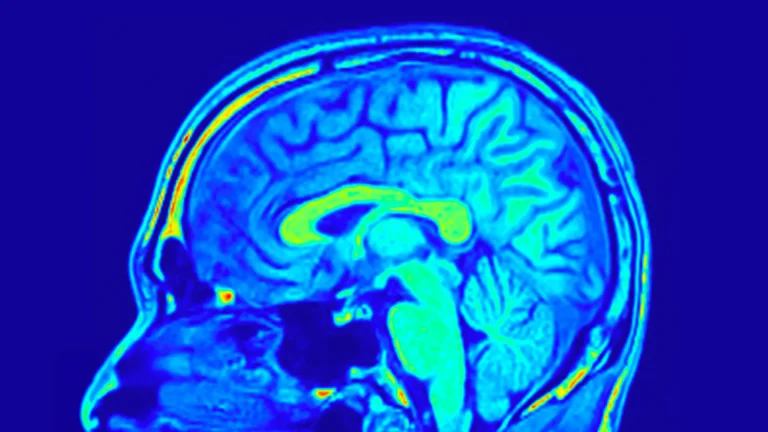

New findings from Johns Hopkins University are prompting a significant re-evaluation of how artificial intelligence systems acquire sophisticated capabilities, suggesting that the inherent design of an AI’s architecture may hold as much, if not more, importance than the sheer volume of data it is exposed to during its development. This groundbreaking research, detailed in the latest issue of Nature Machine Intelligence, indicates that AI models constructed with structural principles mirroring biological brains can exhibit emergent patterns of activity akin to human neural processing even before undergoing any formal training regimen. This observation directly contests the prevailing methodology in the field, which often prioritizes the accumulation of vast datasets and extensive computational resources as the primary drivers of AI advancement.

The conventional approach in artificial intelligence development has largely centered on an iterative process of feeding enormous quantities of data into complex models and employing colossal computing infrastructure for extended periods, a strategy that incurs substantial financial investment, often reaching hundreds of billions of dollars. This contrasts sharply with the remarkable efficiency observed in biological learning, where humans and other organisms can develop sophisticated perceptual abilities with comparatively minimal data input. The Johns Hopkins study posits that this biological efficiency might stem from inherent architectural advantages that evolution has refined over millennia, providing a potent starting point for intelligence acquisition. By emulating these brain-like structural blueprints, AI systems could potentially achieve a more advantageous foundational state, accelerating their learning trajectory and reducing their reliance on data-intensive training protocols.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University embarked on an ambitious project to ascertain whether the fundamental organizational framework of an AI could, in isolation, confer a more human-like initial state, circumventing the necessity for large-scale data exposure. Their investigation meticulously examined three prominent neural network architectures that form the backbone of contemporary AI applications: transformers, which excel in processing sequential data; fully connected networks, where every neuron connects to every neuron in the next layer; and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), specifically designed for processing grid-like data such as images. These established architectural paradigms were subjected to a series of deliberate modifications by the research team, resulting in the creation of dozens of distinct artificial neural network configurations.

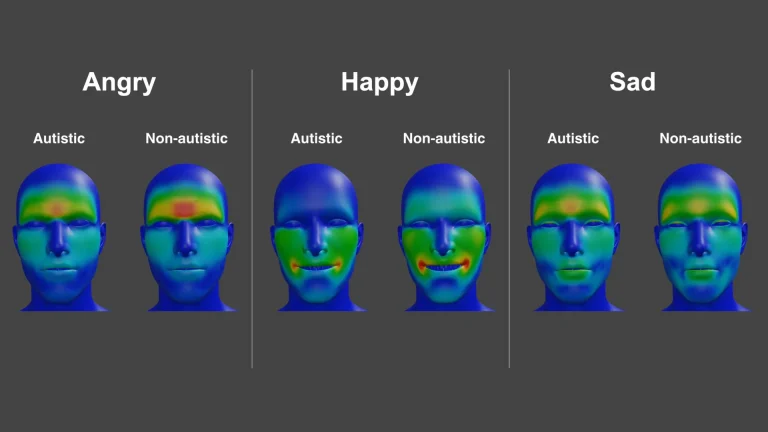

Crucially, none of these newly engineered AI models were subjected to any pre-training procedures; they were essentially presented in their raw, architecturally defined state. Subsequently, these untrained systems were exposed to a curated collection of visual stimuli, encompassing images of everyday objects, human faces, and various animal species. The internal computational activities generated by these AI models were then rigorously compared against neurophysiological data recorded from human and non-human primate brains while they were simultaneously observing the identical visual stimuli. This comparative analysis was designed to identify any emergent similarities in processing patterns, even in the absence of learned associations.

A striking divergence in performance emerged when analyzing the impact of architectural adjustments across the different network types. For transformers and fully connected networks, augmenting the number of artificial neurons within their structures yielded only marginal and largely insignificant shifts in their internal activity patterns. This suggests that simply increasing computational capacity within these conventional designs does not inherently foster more biologically plausible processing. In stark contrast, similar architectural refinements applied to the convolutional neural networks produced demonstrably different outcomes. These modifications led to the emergence of internal activity patterns that exhibited a significantly higher degree of congruence with the neural responses observed in the human brain when processing the same visual information.

The implications of these findings are profound. The study indicates that these untrained convolutional models, solely by virtue of their refined architecture, performed at a level comparable to traditional AI systems that have typically undergone training on millions, and in some cases, billions of images. This suggests that the underlying structural design of an AI system plays a far more critical role in shaping its brain-like behavior and processing capabilities than had been previously assumed. The conventional wisdom has largely posited that the sheer volume of data is the indispensable ingredient for achieving advanced AI functionalities, but this research challenges that fundamental tenet, highlighting the potent influence of inherent design.

Lead author Mick Bonner, an assistant professor of cognitive science at Johns Hopkins University, articulated the significance of these results, stating that if the prevailing notion—that massive data exposure is the paramount factor for developing brain-like AI—were entirely accurate, then achieving such sophisticated cognitive emulation through architectural modifications alone would be an impossibility. The research strongly suggests otherwise, opening the door to a paradigm shift in AI development. By starting with an optimized, biologically inspired blueprint and potentially integrating further insights gleaned from the study of biological systems, the AI community may be on the cusp of dramatically accelerating the learning process in artificial intelligence. This could lead to the development of more efficient, more capable, and less data-hungry AI systems.

The research team is not resting on these laurels; they are actively pursuing further avenues of investigation. Their current efforts are focused on exploring the integration of simplified learning methodologies that are directly inspired by biological processes. The ultimate goal is to pave the way for a new generation of deep learning frameworks. Such frameworks would possess the potential to render AI systems not only faster and more computationally efficient but also significantly less dependent on the gargantuan datasets that have become the hallmark of current AI training regimes. This shift could democratize AI development, making advanced capabilities more accessible and sustainable. The focus is on building smarter foundations, rather than simply overwhelming systems with raw information, suggesting a more elegant and potentially more powerful path forward for artificial intelligence. This work represents a critical step in understanding the fundamental principles that underpin intelligence, whether biological or artificial.