Pancreatic cancer, a notoriously formidable foe in the oncological landscape, has long evaded the efficacy of even the most sophisticated immunotherapeutic interventions, presenting a significant therapeutic challenge. Researchers at Northwestern Medicine have recently illuminated a critical mechanism by which these malignant cells orchestrate their concealment from the body’s natural defenses, simultaneously unveiling a promising experimental countermeasure. Their groundbreaking work reveals that pancreatic tumors employ a sophisticated molecular subterfuge, cloaking themselves in a sugar-based façade that effectively renders them invisible to the immune system. Building upon this discovery, the scientific team has engineered a pioneering monoclonal antibody designed to dismantle this deceptive signal, thereby re-establishing the immune system’s ability to identify and target cancerous cells.

This groundbreaking research marks the first documented identification of this specific immune evasion strategy employed by pancreatic cancer. The study unequivocally demonstrates that by therapeutically disrupting this mechanism with a precisely designed antibody, immune cell activity can be successfully rekindled. In rigorous preclinical investigations utilizing mouse models, the introduction of this antibody prompted a significant resurgence in immune cell engagement, leading to the direct attack and destruction of cancer cells. The culmination of approximately six years of dedicated effort, encompassing the intricate process of uncovering this novel biological pathway, the development of precisely tailored antibodies, and their subsequent validation, represents a monumental leap forward, as articulated by Dr. Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, the senior author of the study and an associate professor of medicine within the division of infectious diseases at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. The palpable success observed in laboratory and animal studies was described by Dr. Abdel-Mohsen as a "major breakthrough." These pivotal findings have been formally published in the esteemed scientific journal Cancer Research, a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The persistent deadliness of pancreatic cancer stems from a confluence of factors, including its frequent diagnosis at advanced stages, the limited spectrum of effective treatment modalities, and a starkly low five-year survival rate, often hovering around a mere 13%. A key differentiator from many other malignancies is its pronounced resistance to conventional immunotherapies. The underlying reason for this resistance, which the Northwestern team sought to unravel, is the notably suppressed level of immune activity within the tumor microenvironment of pancreatic cancers. "Our objective was to understand this deficiency and to explore the possibility of reversing this dynamic, shifting the balance so that immune cells actively combat tumor cells rather than ignoring them or, in some instances, inadvertently supporting their growth," explained Dr. Abdel-Mohsen.

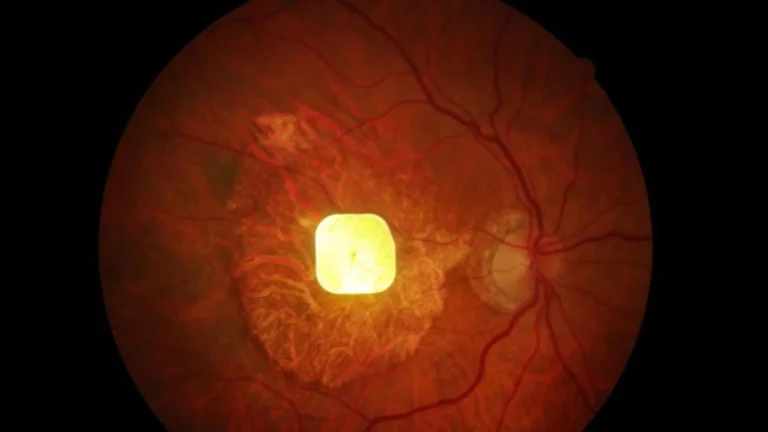

The investigative journey led the research group to a critical discovery: pancreatic tumors adeptly hijack a protective signaling system that is intrinsically part of the normal functioning of healthy cells. Under typical physiological conditions, healthy cells present a specific type of sugar molecule, known as sialic acid, on their external surface. This surface-bound sialic acid serves as a crucial molecular signal to the immune system, essentially communicating a non-aggression pact: "I am not a threat; do not attack me."

The scientific findings revealed that pancreatic cancer cells meticulously replicate this benevolent signaling mechanism to their malignant advantage. The tumors augment the presence of this identical sugar molecule onto a specific surface protein, designated as integrin αvβ3. This sugar-modified protein then establishes a binding interaction with a particular receptor found on the surface of immune cells, identified as Siglec-10. This aberrant binding event effectively triggers a spurious, inhibitory signal within the immune cell, erroneously instructing it to disengage and cease its defensive actions. Dr. Abdel-Mohsen vividly characterized this phenomenon as the tumor "sugar-coating itself—a classic wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing move—to escape immune surveillance."

Following the elucidation of this sophisticated immune cloaking strategy, the Northwestern team embarked on the demanding task of designing and synthesizing monoclonal antibodies capable of neutralizing this deceptive molecular interaction. The subsequent rigorous testing of these experimental antibodies, conducted both in vitro laboratory settings and within two distinct animal models, yielded profoundly encouraging results. These antibodies demonstrably restored immune cell responsiveness and effector function. Immune cells began to actively engulf and destroy cancer cells, and a substantial deceleration in tumor growth was observed in the treated animal cohorts compared to their untreated counterparts. The development of a functional antibody was a painstaking process, involving the extensive screening of thousands of potential candidates. "When you create an antibody, you evaluate what are called hybridomas, cells that produce antibodies. We screened thousands before finding the one that worked," Dr. Abdel-Mohsen noted, underscoring the significant effort involved.

Looking ahead, the researchers are now focused on evaluating the performance of this novel antibody in conjunction with established chemotherapy and immunotherapy regimens. "There’s a strong scientific rationale to believe combination therapy will allow us to reach our ultimate goal: a full remission," Dr. Abdel-Mohsen stated, expressing a clear ambition to achieve complete eradication of the cancer rather than merely partial responses such as a 40% tumor reduction or growth arrest.

The current phase of the research involves the meticulous refinement of the antibody for potential human application, paving the way for crucial early-stage safety and dosage studies. Concurrently, the team is actively investigating the synergistic effects of this antibody when administered alongside standard treatment protocols. Furthermore, efforts are underway to develop a sophisticated diagnostic assay that can precisely identify patients whose tumors exhibit a reliance on this specific sugar-mediated pathway, thereby enabling a more personalized and effective therapeutic approach. If the developmental trajectory continues unimpeded, Dr. Abdel-Mohsen estimates that this innovative treatment could potentially become accessible to patients within approximately five years. The implications of this discovery may well transcend the confines of pancreatic cancer. "We’re now asking whether the same sugar-coat trick shows up in other hard-to-treat cancers, such as glioblastoma, and in non-cancer diseases where the immune system is misled," he added, indicating the broad potential impact of this research.

Dr. Abdel-Mohsen’s laboratory is at the forefront of glyco-immunology, an emergent and rapidly evolving field dedicated to understanding the profound influence of carbohydrates on immune system function. "We’re just scratching the surface of this field," he remarked, emphasizing the vast unexplored territory. "Here at Northwestern, we’re positioned to turn these sugar-based insights into real treatments for cancer, infectious diseases and aging-related conditions." Dr. Abdel-Mohsen is an integral member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. The scientific paper detailing these findings is titled "Targeting Interactions Between Siglec-10 and αvβ3 Integrin Enhances Macrophage-Mediated Phagocytosis of Pancreatic Cancer." The research was generously supported in part by Northwestern University’s Center for Human Immunobiology Pilot Award for the 2025-2026 period, awarded to Dr. Abdel-Mohsen. Additional funding for his work has been provided by several National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants, including R01AG092241, R01AI165079, R01AA029859, R01DK123733, R01AI189353, and R01NS117458, as well as through the NIH-funded BEAT-HIV Martin Delaney Collaboratory to Cure HIV-1 Infection (grant number 1UM1AI126620).