A comprehensive laboratory investigation has identified a significant number of commonly encountered synthetic chemicals as detrimental to the microbial communities residing within a healthy human gut. The findings reveal that 168 distinct chemical compounds, widely disseminated through everyday products and environmental pathways, possess the capacity to impede or halt the proliferation of these essential microorganisms, which are pivotal for maintaining overall physiological well-being.

The pervasive nature of these chemical agents means that individuals are routinely exposed to them via a multitude of sources, including dietary intake, potable water supplies, and broader environmental contact. Prior to this extensive analysis, many of these substances were not considered to have any impact on the bacterial populations within the digestive tract. This research challenges that assumption, highlighting a previously unrecognized threat to gut health.

Emerging concerns regarding the potential for these chemicals to foster antibiotic resistance have introduced a new layer of complexity to the findings. When exposed to these environmental chemical stressors, certain gut bacteria exhibit adaptive responses aimed at survival. A particularly alarming consequence of these adaptations is the acquisition of resistance to critical antibiotic medications, such as ciprofloxacin. If similar adaptive mechanisms were to manifest within the human body, it could lead to a scenario where common infections become considerably more challenging to treat effectively, posing a significant public health challenge.

This groundbreaking study was spearheaded by a team of researchers affiliated with the University of Cambridge. Their rigorous experimental approach involved systematically evaluating the effects of 1,076 different chemical contaminants on 22 distinct species of gut bacteria under controlled laboratory conditions. This extensive screening process provided a robust dataset for identifying the specific chemicals and their impact on microbial viability and function.

Among the chemicals identified as posing the greatest risk to beneficial gut bacteria are agricultural chemicals, including herbicides and insecticides routinely applied to food crops. Furthermore, industrial compounds, such as those used in the manufacturing of flame retardants and plastics, were also found to exhibit significant toxicity towards these vital microorganisms. The broad spectrum of these harmful chemicals underscores the widespread nature of the potential threat.

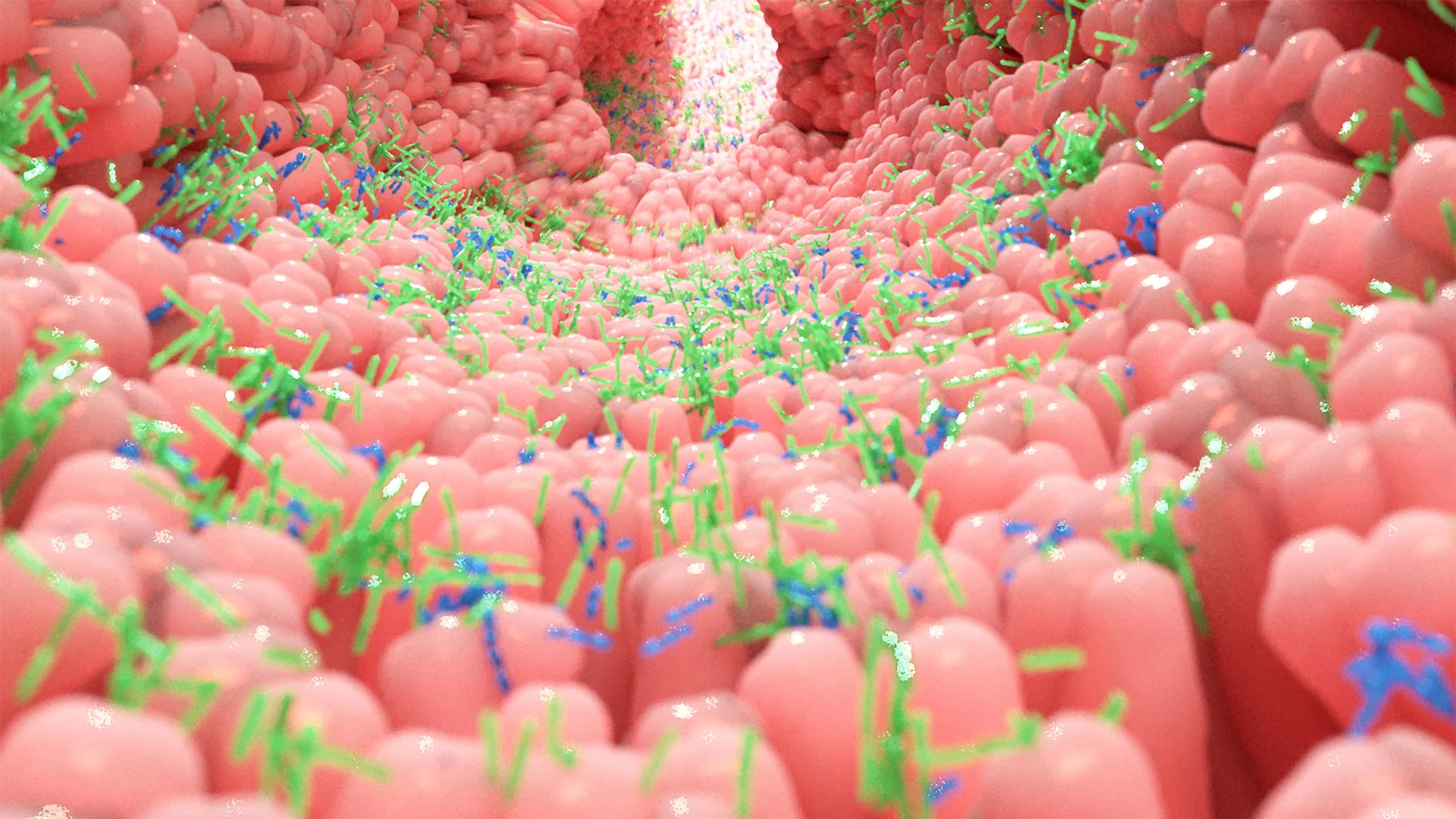

The human gut microbiome is a remarkably complex ecosystem, housing an estimated 4,500 different species of bacteria. These microorganisms perform an array of indispensable functions that contribute to the proper functioning of the human body. A disruption to this delicate microbial balance has been implicated in a wide spectrum of health issues, ranging from gastrointestinal disorders and obesity to compromised immune system efficacy and even adverse effects on mental health. The discovery that everyday chemicals can directly assault this critical system adds a new dimension to our understanding of environmental health impacts.

A significant gap has been identified in current chemical safety assessment protocols, which largely overlook the intricate role of the gut microbiome. Traditional safety evaluations are typically designed to identify chemicals that target specific organisms or biological processes, such as insecticides engineered to harm insects. This narrow focus inadvertently omits the potential for these chemicals to exert deleterious effects on the vast and vital community of microbes within the human gut.

Leveraging the extensive data generated from their laboratory experiments, the research team has developed a sophisticated machine learning model. This innovative tool is designed to predict the likelihood of industrial chemicals, whether currently in circulation or under development, causing harm to human gut bacteria. The groundbreaking findings and the predictive model have been formally documented and published in the esteemed scientific journal, Nature Microbiology.

The researchers are advocating for a fundamental re-evaluation of chemical safety paradigms. Dr. Indra Roux, a lead researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit and the study’s first author, expressed surprise at the broad-ranging impact of chemicals designed for single-target applications. "We’ve found that many chemicals designed to act only on one type of target, say insects or fungi, also affect gut bacteria," Dr. Roux stated. "We were surprised that some of these chemicals had such strong effects. For example, many industrial chemicals like flame retardants and plasticizers — that we are regularly in contact with — weren’t thought to affect living organisms at all, but they do." This observation highlights a critical oversight in the design and testing of chemical products.

Professor Kiran Patil, a senior author of the study and also based at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit, emphasized the transformative potential of their large-scale research. "The real power of this large-scale study is that we now have the data to predict the effects of new chemicals, with the aim of moving to a future where new chemicals are safe by design," Professor Patil remarked. This forward-looking perspective suggests a shift towards proactive chemical safety measures that consider microbial impacts from the outset of product development.

Dr. Stephan Kamrad, another key researcher involved in the project, underscored the necessity of expanding the scope of safety assessments. "Safety assessments of new chemicals for human use must ensure they are also safe for our gut bacteria, which could be exposed to the chemicals through our food and water," Dr. Kamrad urged. This call for a more holistic approach recognizes the interconnectedness of human health and the gut microbiome.

Despite the significant advancements made by this study, there remain considerable unknowns regarding the real-world implications of environmental chemical exposure on the gut microbiome and, consequently, on human health. The researchers acknowledge that the precise concentrations of these chemicals that ultimately reach the digestive system are not yet clearly understood. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the associated risks, future research endeavors will need to meticulously track chemical exposure pathways throughout the body.

Professor Patil reiterated the importance of bridging the gap between laboratory findings and real-world observations. "Now we’ve started discovering these interactions in a laboratory setting it’s important to start collecting more real-world chemical exposure data, to see if there are similar effects in our bodies," he advised. This sentiment highlights the critical need for epidemiological studies and biomonitoring to validate the laboratory findings in human populations.

In the interim, while further research is conducted, the scientists recommend practical measures to mitigate exposure to these harmful chemicals. These simple yet effective steps include thoroughly washing fruits and vegetables before consumption and refraining from the use of pesticides in domestic gardening. Such proactive measures can contribute to reducing the overall chemical burden on the body and, by extension, on the delicate gut microbiome.