A groundbreaking development in neurotechnology promises to redefine human interaction with digital systems and unlock unprecedented therapeutic avenues for a spectrum of neurological conditions, including epilepsy, spinal cord injuries, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke aftermath, and visual impairments. This innovative approach establishes a minimally invasive, exceptionally high-capacity communication channel directly with the brain, holding significant potential for enhanced seizure management and the restoration of motor, speech, and visual functions. The core of this transformative technology lies in its remarkable miniaturization and its capacity for ultra-fast data transmission, achieved through a sophisticated brain-computer interface (BCI) centered on a single, advanced silicon chip. This collaborative endeavor, involving leading institutions such as Columbia University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania, has culminated in the creation of the Biological Interface System to Cortex (BISC).

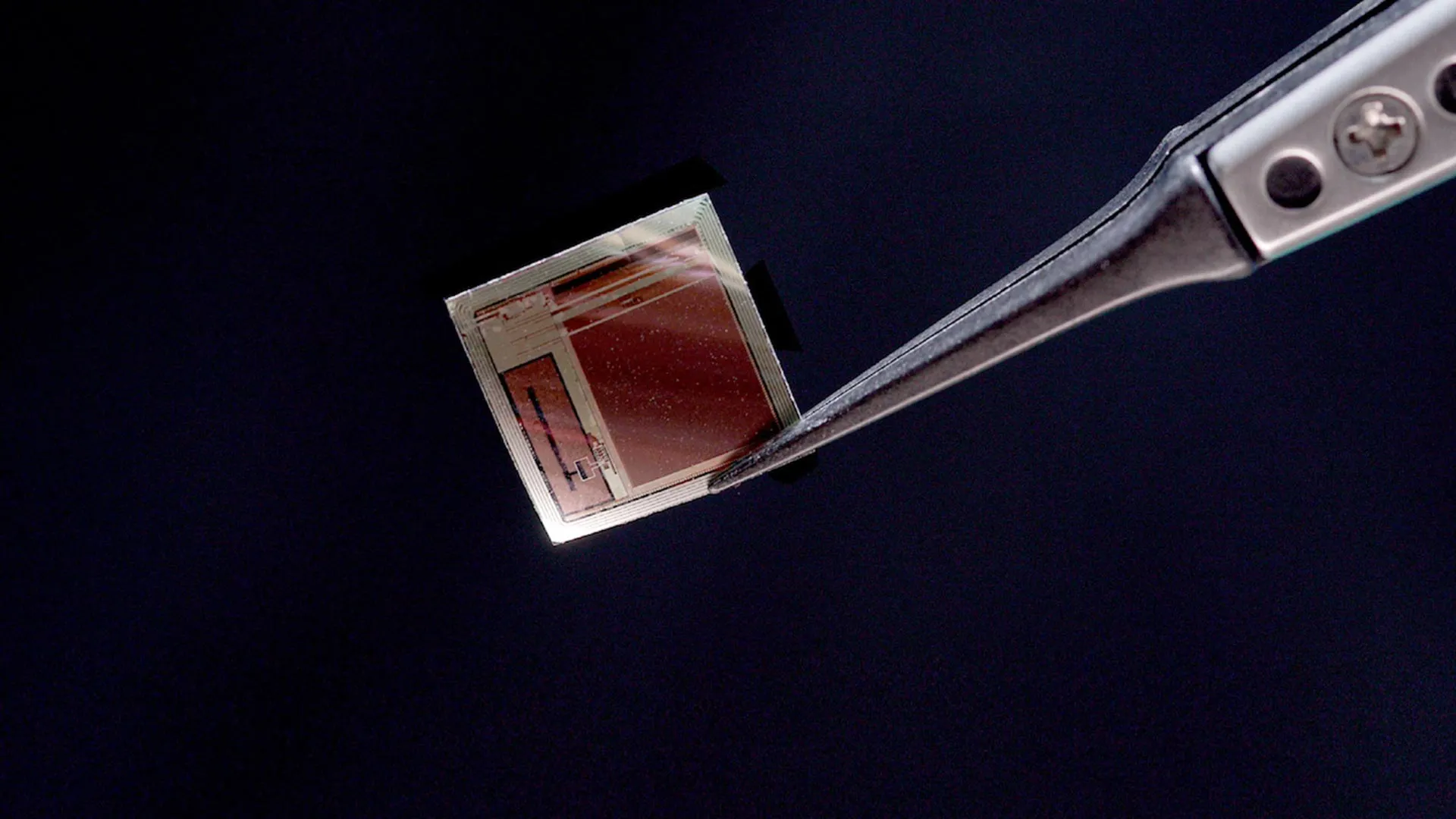

The detailed architecture of BISC is elucidated in a recent study published in the esteemed journal Nature Electronics. The system comprises three primary components: the chip-level implant itself, a wearable external "relay station," and the essential software infrastructure required for its operation. Traditional implantable systems often necessitate bulky electronic modules, necessitating considerable internal space. In contrast, the BISC implant is a singular integrated circuit, ingeniously engineered to be so thin that it can be delicately placed within the subdural space, resting on the brain’s surface with minimal physical intrusion. Ken Shepard, a distinguished professor at Columbia University with joint appointments in electrical engineering, biomedical engineering, and neurological sciences, who co-led the engineering aspects of this project, highlighted this critical design advantage. He explained that the implant’s wafer-thin profile allows it to reside on the brain like "a piece of wet tissue paper," a stark contrast to the substantial bulk of conventional implants.

The capacity of this implant to effectively decode neural activity was significantly bolstered by the expertise of Andreas S. Tolias, PhD, a professor at Stanford University’s Byers Eye Institute and a co-founding director of the Enigma Project. Professor Tolias’s extensive background in training artificial intelligence (AI) systems using large-scale neural recordings, including those generated by BISC, proved instrumental in validating the implant’s analytical capabilities. According to Tolias, BISC effectively transforms the cortical surface into a high-bandwidth portal, facilitating direct, minimally invasive communication with AI and external devices for both data input and output. He further emphasized that the single-chip design offers unparalleled scalability, paving the way for the development of adaptive neuroprosthetics and brain-AI interfaces capable of addressing a wide array of neuropsychiatric disorders, with epilepsy being a prime example.

The clinical dimension of this pioneering work was spearheaded by Dr. Brett Youngerman, an assistant professor of neurological surgery at Columbia University and a neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Dr. Youngerman underscored the profound potential of this high-resolution, high-data-throughput device to revolutionize the management of neurological conditions, ranging from epilepsy to paralysis. He, alongside Professor Shepard and Dr. Catherine Schevon, an epilepsy neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University, has successfully secured a National Institutes of Health grant to investigate the application of BISC in treating drug-resistant epilepsy. Dr. Youngerman articulated a core principle of advanced BCI development: maximizing the flow of information to and from the brain while minimizing surgical invasiveness. He asserted that BISC represents a significant advancement on both these fronts, surpassing existing technologies.

Professor Shepard attributed the feasibility of such a compact yet powerful device to advancements in semiconductor technology, which have enabled the integration of computing power previously requiring room-sized installations into pocket-sized devices. He drew a parallel between these computational advancements and the current progress in medical implantables, where complex electronic functionalities can now be integrated into the body with minimal spatial footprint.

The engineering behind this next-generation BCI diverges significantly from conventional approaches. Current medical-grade BCIs typically employ multiple discrete microelectronic components, such as amplifiers, data converters, and radio transmitters. These individual parts necessitate a relatively large implanted housing, which is either surgically placed by removing a section of the skull or located elsewhere in the body, such as the chest, with wires extending to the brain. BISC, in contrast, integrates all these essential functions onto a single complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit. This chip has been meticulously thinned to a mere 50 micrometers, occupying less than one-thousandth the volume of a typical implant. With a total volume of approximately 3 cubic millimeters, this flexible chip is capable of conforming to the intricate contours of the brain’s surface. This micro-electrocorticography (µECoG) device is equipped with an impressive array of 65,536 electrodes, supporting 1,024 recording channels and 16,384 stimulation channels. The utilization of standard semiconductor industry manufacturing processes makes BISC highly amenable to large-scale production.

The integrated circuit design of the BISC chip encompasses a radio transceiver, a wireless power circuit, digital control electronics, power management systems, data converters, and the analog circuitry essential for both neural signal recording and stimulation. The external relay station serves as a crucial link, providing both power and data communication via a specialized ultrawideband radio link that achieves a remarkable data transfer rate of 100 megabits per second (Mbps). This throughput is at least 100 times greater than that of any other wireless BCI currently available. Functioning as an 802.11 WiFi device, the relay station seamlessly bridges the implant to any compatible computer system.

Further enhancing its capabilities, BISC incorporates its own proprietary instruction set and a comprehensive software environment, effectively creating a specialized computing system tailored for brain interfaces. The high-bandwidth recording achieved by the system enables brain signals to be processed by sophisticated machine-learning and deep-learning algorithms. These advanced algorithms can then interpret complex intentions, perceptual experiences, and various brain states with unprecedented accuracy. Professor Shepard emphasized that by consolidating all functionalities onto a single silicon substrate, the researchers have dramatically enhanced the miniaturization, safety, and overall power of brain interfaces.

The advanced semiconductor fabrication techniques employed in the creation of the BISC implant are rooted in TSMC’s 0.13-micrometer Bipolar-CMOS-DMOS (BCD) technology. This sophisticated manufacturing process integrates three distinct semiconductor technologies onto a single chip, enabling the efficient co-existence of digital logic (from CMOS), high-current and high-voltage analog functions (from bipolar and DMOS transistors), and power management components (from DMOS). This synergistic integration is fundamental to BISC’s exceptional performance characteristics.

The journey from laboratory development to potential clinical application has involved a critical partnership between Professor Shepard’s team and Dr. Youngerman at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. This collaboration has focused on developing and refining surgical procedures for the safe implantation of the ultra-thin device in preclinical models, successfully validating the production of high-quality, stable neural recordings. Initial short-term intraoperative studies involving human patients are currently underway. Dr. Youngerman commented that these early investigations provide invaluable insights into the device’s performance within a genuine surgical context. He noted that the implants can be introduced through a minimally invasive cranial incision and gently placed directly onto the brain’s surface within the subdural space. The paper-thin form factor, coupled with the absence of brain-penetrating electrodes or wires tethering the implant to the skull, significantly minimizes tissue reactivity and mitigates signal degradation over extended periods.

Extensive preclinical research focusing on the motor and visual cortices was conducted in close collaboration with Professor Tolias and Bijan Pesaran, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania, both recognized leaders in computational and systems neuroscience. Professor Pesaran expressed his enthusiasm for BISC’s extreme miniaturization, viewing it as a pivotal platform for future generations of implantable technologies that may also integrate other sensory modalities, such as light and sound, with the brain. The development of BISC was supported by the Neural Engineering System Design program of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), leveraging Columbia University’s profound expertise in microelectronics, the advanced neuroscience programs at Stanford and Penn, and the surgical capabilities of NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

To accelerate the transition of this technology towards practical clinical adoption, researchers from Columbia and Stanford have established Kampto Neurotech. This startup, founded by Dr. Nanyu Zeng, a Columbia electrical engineering alumnus and a key engineer on the project, is actively producing research-ready versions of the BISC chip and is in the process of securing the necessary funding to prepare the system for human clinical trials. Dr. Zeng characterized BISC as representing a fundamentally different paradigm in the construction of BCI devices, stating that its technological capabilities significantly surpass those of competing systems by several orders of magnitude.

As artificial intelligence continues its rapid evolution, BCIs are experiencing a surge in development, not only for their potential to restore lost functionalities in individuals with neurological disorders but also for prospective future applications aimed at enhancing normal human capabilities through direct brain-to-computer communication. Professor Shepard envisions a future where the seamless interaction between the brain and AI systems extends beyond research applications to profoundly benefit humanity. He posits that this integration could fundamentally alter how neurological disorders are treated, how humans interface with machines, and ultimately, how humanity engages with the burgeoning field of artificial intelligence.