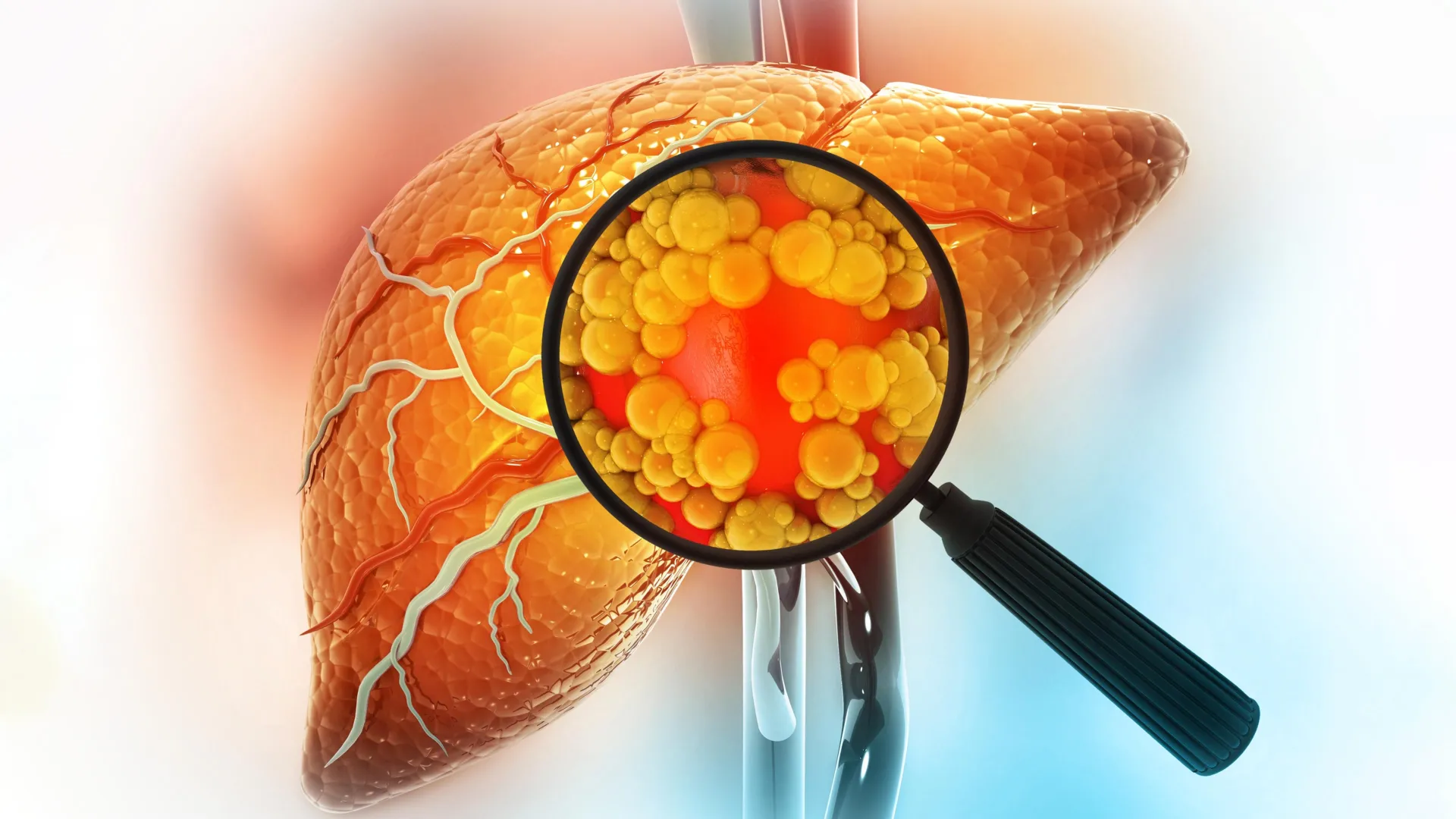

New scientific insights emerging from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) illuminate a critical mechanism by which prolonged consumption of high-fat diets can significantly elevate the risk of developing liver cancer. This extensive investigation reveals that the liver, a vital organ responsible for numerous metabolic processes, undergoes a profound cellular transformation when subjected to persistent fatty insults. Rather than simply accumulating fat, liver cells, specifically hepatocytes, are compelled to adopt a more rudimentary, stem-cell-like identity to survive the relentless stress. While this adaptation offers a short-term survival advantage, it inadvertently primes these cells for malignant proliferation, laying a dangerous groundwork for cancerous growth.

The study, published in the prestigious journal Cell on December 22, delves into the intricate molecular choreography that unfolds within the liver under conditions of dietary fat overload. Researchers observed that repeated exposure to excessive lipids prompts hepatocytes to abandon their highly specialized functions. This developmental regression, a shift towards a more primitive cellular state, is a survival response; these less differentiated cells possess a greater inherent capacity to endure cellular damage and inflammation. However, this very plasticity, this shedding of mature identity, simultaneously strips away natural safeguards against uncontrolled division, making the cells far more susceptible to accumulating mutations that can lead to cancer.

"When cells are repeatedly subjected to severe challenges, such as the metabolic strain imposed by a high-fat diet, they will invariably adopt strategies to persist," explained Alex K. Shalek, a principal investigator in the study and a distinguished professor at MIT. "These survival mechanisms, while effective in the short term, unfortunately come at the cost of increased vulnerability to the development of tumors."

The research team meticulously identified several key regulatory elements, known as transcription factors, that orchestrate this crucial cellular transition. These molecular switches appear to control the switch between mature and primitive cellular states. The identification of these specific factors opens up promising avenues for therapeutic intervention, potentially leading to the development of novel pharmaceutical agents designed to mitigate liver cancer risk in individuals predisposed to such conditions.

Leading the investigation were a trio of distinguished scientists: Alex K. Shalek, director of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Sciences (IMES) and a professor in the Department of Chemistry; Ömer Yilmaz, an associate professor of biology at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute; and Wolfram Goessling, co-director of the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. The groundbreaking findings were co-authored by MIT graduate student Constantine Tzouanas, former MIT postdoctoral researcher Jessica Shay, and Marc Sherman, a postdoctoral fellow at Massachusetts General Brigham.

The pathway from a fatty diet to liver malignancy is complex and often insidious. Excessive dietary fat can precipitate inflammation and the excessive accumulation of fat within liver cells, a condition broadly termed steatotic liver disease. This metabolic dysfunction, which can also stem from chronic alcohol abuse and other long-term stressors, can progress through stages of liver damage, including cirrhosis, ultimately culminating in liver cancer. The MIT study sought to unravel the precise molecular cascade initiated by these dietary challenges.

To meticulously chart these cellular responses, the researchers employed a sophisticated technique called single-cell RNA sequencing. This advanced methodology allowed them to track the precise genetic activity within individual liver cells at various points during the progression of diet-induced liver disease in laboratory mice. By analyzing gene expression patterns, they could observe how cellular behavior shifted from initial inflammation and tissue damage to eventual scar formation and the development of cancerous tumors.

In the early stages of the high-fat diet regimen, hepatocytes began to activate a specific set of genes that are known to promote cell survival under duress. These genetic activations included pathways that inhibit programmed cell death, thereby preserving cellular integrity, and others that encourage continued cell division. Concurrently, genes critical for the liver’s normal metabolic functions, including those responsible for processing nutrients and synthesizing essential proteins, began to be systematically deactivated.

"This phenomenon appears to represent a stark trade-off," commented Constantine Tzouanas, one of the study’s lead authors. "The individual cell prioritizes its own immediate survival within a hostile environment, even if it means compromising the collective function and health of the entire liver tissue."

The speed at which these genetic alterations occurred varied. Some transcriptional changes were remarkably rapid, while others unfolded over more extended periods. For instance, the downregulation of genes involved in metabolic enzyme production was a more gradual process. By the conclusion of the experimental timeline, a significant majority of the mice that had been fed a high-fat diet had developed liver cancer.

The implications of liver cells reverting to a less mature, more primitive state are profound for cancer development. When a liver cell exists in this de-differentiated condition, it becomes significantly more prone to transforming into a cancerous cell should any subsequent genetic mutations occur. This is because these cells have already initiated the expression of genes that are typically activated during cancerous proliferation.

"These cells have already engaged the genetic machinery necessary for uncontrolled growth," Tzouanas elaborated. "They have effectively shed the mature cellular identity that would normally impose constraints on their proliferation. Consequently, if a cell acquires the wrong mutation, it has a substantial head start in acquiring the hallmarks of cancer."

The study also pinpointed several genes that play a crucial role in coordinating this reversion to a less mature cellular state. Intriguingly, one of the genes identified as a potential target, the thyroid hormone receptor, is already the focus of an approved drug used to treat a severe form of steatotic liver disease characterized by fibrosis. Furthermore, a compound that activates another enzyme highlighted in the research, HMGCS2, is currently undergoing clinical evaluation for its therapeutic potential in treating steatotic liver conditions.

Another significant molecular target that emerged from this research is a transcription factor known as SOX4. This factor is typically active during embryonic development and in a restricted number of adult tissues, but not normally in the liver. Its unexpected activation within liver cells under high-fat dietary conditions therefore stands out as a particularly noteworthy finding.

To validate their discoveries made in animal models, the researchers sought to determine if similar cellular transformations occur in humans experiencing liver disease. They meticulously analyzed liver tissue samples obtained from patients at various stages of liver pathology, including those who had not yet developed cancerous growths.

The patterns observed in human tissues remarkably mirrored those found in the mice. As liver disease progressed, genes essential for normal liver function showed decreased activity, while genes associated with immature cell states exhibited increased expression. The researchers also discovered that these specific gene expression profiles could serve as a predictive indicator of patient survival outcomes.

"We observed that patients with higher levels of expression for these pro-survival genes, which are activated in response to a high-fat diet, tended to have shorter survival times after the development of tumors," Tzouanas stated. "Similarly, individuals with lower expression of genes supporting the liver’s normal functional capacity also experienced reduced survival durations."

While the mice in the study developed liver cancer within approximately one year, the researchers estimate that the analogous process in humans likely unfolds over a considerably longer period, potentially spanning two decades. This timeline is subject to variation based on individual dietary habits, genetic predispositions, and the presence of other contributing risk factors, such as excessive alcohol consumption and viral infections, which can also drive liver cells towards a less differentiated state.

A crucial question now facing the scientific community is whether the cellular damage induced by dietary fat can be reversed. The research team is actively pursuing this line of inquiry, with future studies planned to investigate the potential of dietary interventions and pharmacological approaches to restore normal liver cell behavior. This includes examining the impact of returning to a balanced, healthy diet and evaluating the efficacy of weight-loss medications like GLP-1 agonists.

Moreover, the researchers aim to conduct further in-depth investigations into the therapeutic potential of the identified transcription factors as drug targets. The goal is to develop strategies that can effectively prevent damaged liver tissue from progressing to a cancerous state.

"We now possess a deeper understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms and have identified several novel molecular targets," concluded Shalek. "This knowledge provides us with fresh perspectives and potential avenues for improving patient outcomes in liver disease."

The ambitious scope of this research was supported by a combination of funding sources, including a Fannie and John Hertz Foundation Fellowship, a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, grants from the National Institutes of Health, and the MIT Stem Cell Initiative through Foundation MIT.