A groundbreaking advancement in neurobiology has unveiled critical insights into the intricate processes governing human brain development and connectivity, offering a novel lens through which to examine neurological and psychiatric disorders. Researchers in Japan have successfully engineered sophisticated, multi-regional brain models, termed assembloids, from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. These innovative structures accurately replicate fundamental human neural circuits within a laboratory setting, enabling scientists to observe, for the first time in such detail, the formative interactions between different brain regions. This seminal work, recently published in the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, specifically highlights the thalamus’s pivotal role in orchestrating the precise assembly and functional maturation of specialized neural networks within the cerebral cortex.

Understanding the complex tapestry of neural circuits within the human brain is paramount to deciphering the very essence of human cognition, perception, and behavior. The cerebral cortex, the brain’s outermost layer, is a highly convoluted structure responsible for our most advanced functions, including language, memory, decision-making, and conscious thought. Its functionality hinges upon billions of neurons forming billions of highly specific connections, communicating through electrical and chemical signals. Any disruption to the formation, maturation, or maintenance of these delicate connections can have profound consequences, manifesting as a spectrum of neurodevelopmental conditions. For individuals affected by disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or schizophrenia, atypical cortical circuit development or aberrant functioning is often a defining characteristic. Consequently, unraveling the precise mechanisms by which these cortical circuits are established and fine-tuned during development is not merely an academic pursuit; it is a crucial endeavor to identify the underlying biological etiologies of these debilitating conditions and to pave the way for effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions.

The journey to understanding these complex processes has historically faced formidable challenges. Directly studying the human brain’s developmental trajectory in real-time, especially its early stages of circuit formation, is fraught with ethical and practical limitations. Access to living human brain tissue, particularly during critical developmental windows, is severely restricted. Traditional two-dimensional cell cultures, while useful for basic cellular studies, fail to capture the three-dimensional architecture, cellular diversity, and complex intercellular interactions characteristic of an intact brain. This inherent difficulty has long necessitated reliance on animal models, predominantly rodents, which, despite offering valuable insights, possess significant anatomical and functional differences from the human brain, particularly in the highly evolved cerebral cortex. Prior research in murine models, for instance, had indeed implicated the thalamus as a key organizer of cortical circuitry. However, the exact dynamics of thalamo-cortical interaction during human brain circuit formation remained largely enigmatic due to these inherent study constraints.

To circumvent these persistent hurdles, the scientific community has increasingly turned to stem cell-derived organoids. These three-dimensional cellular aggregates, cultivated from iPS cells, spontaneously self-organize into structures that mimic the architecture and cellular composition of real organs. Induced pluripotent stem cells themselves represent a revolutionary breakthrough, as they are adult somatic cells (like skin cells) that have been genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic-like state, giving them the ability to differentiate into virtually any cell type in the body. This allows researchers to generate patient-specific cells and tissues without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells. While brain organoids have offered an unprecedented opportunity to model aspects of human brain development in vitro, a single organoid typically represents only one brain region, failing to recapitulate the intricate, long-range communication that occurs between distinct brain areas. It is precisely this inter-regional interaction that is fundamental to the brain’s integrative functions.

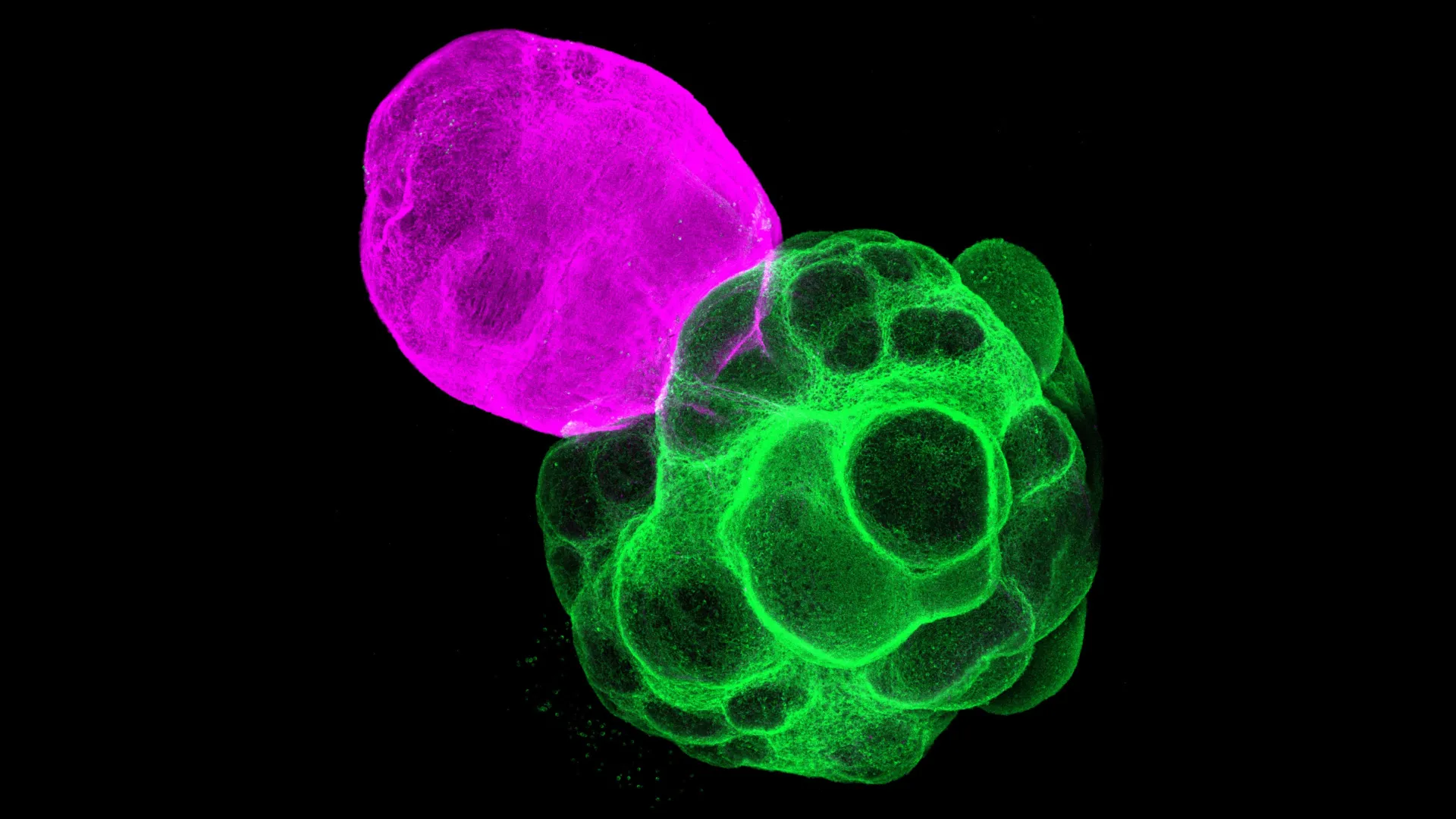

Recognizing this limitation, researchers have pioneered the development of assembloids – a more advanced generation of in vitro brain models created by physically fusing two or more distinct organoids. This innovative approach allows scientists to construct complex, multi-regional systems that can mimic the developmental interactions between different brain components. The team at the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Nagoya University, led by Professor Fumitaka Osakada and graduate student Masatoshi Nishimura, leveraged this assembloid technology to specifically model the dynamic interplay between the human thalamus and cerebral cortex. Their methodology involved a meticulous, multi-step process: first, they independently generated separate organoids resembling either cortical or thalamic tissue, both derived from human iPS cells. Once these individual organoids reached a specific developmental stage, they were carefully co-cultured and allowed to fuse, thereby creating a functional thalamus-cortex assembloid. This ingenious system provided a unique experimental platform to observe how these two crucial brain regions communicate and influence each other’s development in a controlled, human-specific context.

Upon observing these lab-grown miniature brain circuits, the researchers were struck by their remarkable fidelity to in vivo development. They meticulously tracked the growth and differentiation of neural processes within the assembloids. A key observation was the directed outgrowth of nerve fibers: axons originating from the thalamic region extended purposefully towards the developing cortical tissue, while, reciprocally, cortical axons projected towards the thalamic component. Crucially, these projecting fibers successfully formed functional synaptic connections with their target neurons, demonstrating a level of structural and organizational complexity that closely mirrors the sophisticated connectivity observed in the developing human brain. This biomimetic axon guidance and synapse formation provided compelling evidence that the assembloids were indeed recapitulating fundamental aspects of human brain wiring.

Beyond mere structural resemblance, the team delved into the functional implications of this inter-regional communication. To assess the impact of thalamic input on cortical maturation, they performed a comparative analysis of gene expression profiles. They contrasted the genetic activity within the cortical region of the assembloid (which was connected to the thalamus) against that of a standalone cortical organoid grown in isolation. The results were illuminating: the cortical tissue within the thalamo-cortical assembloid exhibited a gene expression signature indicative of significantly greater developmental maturity. This finding strongly suggested that the active communication and reciprocal signaling between the thalamus and cortex are not merely incidental but are crucial drivers promoting cortical growth, differentiation, and the establishment of its advanced functional architecture. The presence of the thalamic partner appeared to accelerate and refine the developmental trajectory of the cortical tissue.

Further investigations explored the electrophysiological properties of these assembloids, specifically focusing on how neural signals propagated through the interconnected networks. The scientists observed the emergence of synchronized neural activity, characterized by wave-like patterns of electrical impulses that spread from the thalamic region into the connected cortex. This synchronized firing of neurons is a hallmark of healthy brain function, essential for processes like sensory integration, attention, and memory formation. To pinpoint the specific neuronal populations involved in this synchronized activity, the researchers precisely measured the electrical behavior of three primary types of cortical excitatory neurons: intratelencephalic (IT), pyramidal tract (PT), and corticothalamic (CT) neurons. Each of these neuron types plays distinct roles based on their projection patterns. IT neurons primarily connect within the cortex itself, PT neurons project to subcortical areas involved in motor control, and CT neurons form feedback loops by projecting back to the thalamus.

The analysis revealed a fascinating specificity: synchronized activity, driven by thalamic input, was predominantly observed in PT and CT neurons. In contrast, IT neurons, which do not directly project to the thalamus, did not exhibit the same level of coordinated activity. This differential response is profoundly significant. It implies that thalamic input does not merely provide a general excitatory boost to the cortex; rather, it selectively strengthens and coordinates specific neuronal types that are directly involved in forming reciprocal connections with the thalamus or projecting to other critical subcortical structures. This selective strengthening and functional coordination are crucial for the proper establishment of highly specialized cortical networks, enabling them to mature into efficient processing units capable of integrating sensory information and executing complex behaviors.

By successfully recreating and meticulously analyzing these human neural circuits using advanced assembloid technology, the Nagoya University team has established a profoundly powerful and versatile platform. This innovative system transcends the limitations of previous models, offering an unprecedented opportunity to delve into the fundamental mechanisms governing human brain circuit formation, function, and the subtle cellular and molecular differences that underpin various brain cell types. The implications of this research are far-reaching, promising to revolutionize several areas of neuroscience and clinical medicine.

Firstly, this assembloid platform provides an invaluable tool for modeling neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Researchers can now generate patient-specific iPS cells from individuals with conditions like ASD or schizophrenia, then create assembloids from these cells. By comparing the circuit formation and functional properties of "diseased" assembloids with those derived from healthy controls, scientists can identify specific developmental aberrations, cellular dysfunctions, or connectivity defects that contribute to the pathology of these disorders. This could lead to a deeper understanding of disease etiology and the identification of novel biomarkers.

Secondly, this technology holds immense promise for drug discovery and therapeutic development. The assembloid system offers a high-throughput, human-specific platform for screening potential pharmacological agents. Researchers can test the efficacy of various compounds in correcting identified circuit abnormalities or restoring normal neuronal function in disease models. This could significantly accelerate the development of new treatments, potentially reducing reliance on less predictive animal models and improving the success rate of clinical trials. The ability to create patient-specific assembloids also opens avenues for personalized medicine, where treatments could be tailored to an individual’s unique genetic and cellular profile.

Beyond disease modeling, the assembloid approach will undoubtedly contribute to fundamental neuroscience. It provides a robust system to study aspects of human-specific brain development, potentially shedding light on the evolutionary processes that have endowed our species with its unique cognitive capabilities. Questions regarding the precise timing of critical developmental windows, the influence of genetic predispositions, and the impact of environmental factors on circuit formation can now be addressed with unprecedented detail.

As Professor Osakada eloquently summarized, "We have made significant progress in the constructivist approach to understanding the human brain by reproducing it. We believe these findings will help accelerate the discovery of mechanisms underlying neurological and psychiatric disorders, as well as the development of new therapies." This pioneering work marks a critical juncture in neuroscience, moving beyond static observations to dynamic, functional modeling, and bringing us closer to unraveling the profound mysteries of the human brain and addressing the immense challenges posed by its many disorders. The future of neurobiological research, empowered by such sophisticated in vitro models, appears brighter than ever.