Affecting an estimated 2.3 million individuals globally, multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune condition characterized by a relentless assault on the central nervous system. A significant majority, around 80% of those diagnosed, experience the disease’s insidious progression within the cerebellum, a critical brain structure governing equilibrium and the intricate coordination of bodily movements. The ensuing damage within this region precipitates a cascade of debilitating symptoms, including tremors, a pervasive sense of unsteadiness, and profound difficulties in achieving muscular control. Over time, these functional deficits tend to escalate as the brain’s healthy tissue within the cerebellum undergoes gradual attrition.

Recent groundbreaking investigations spearheaded by researchers at the University of California, Riverside, are shedding new light on the underlying reasons for this progressive deterioration. Published in the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this research identifies compromised mitochondria as a principal architect of the relentless breakdown of cerebellar neurons, specifically the Purkinje cells, a process intricately linked to the exacerbation of motor control issues experienced by individuals with MS.

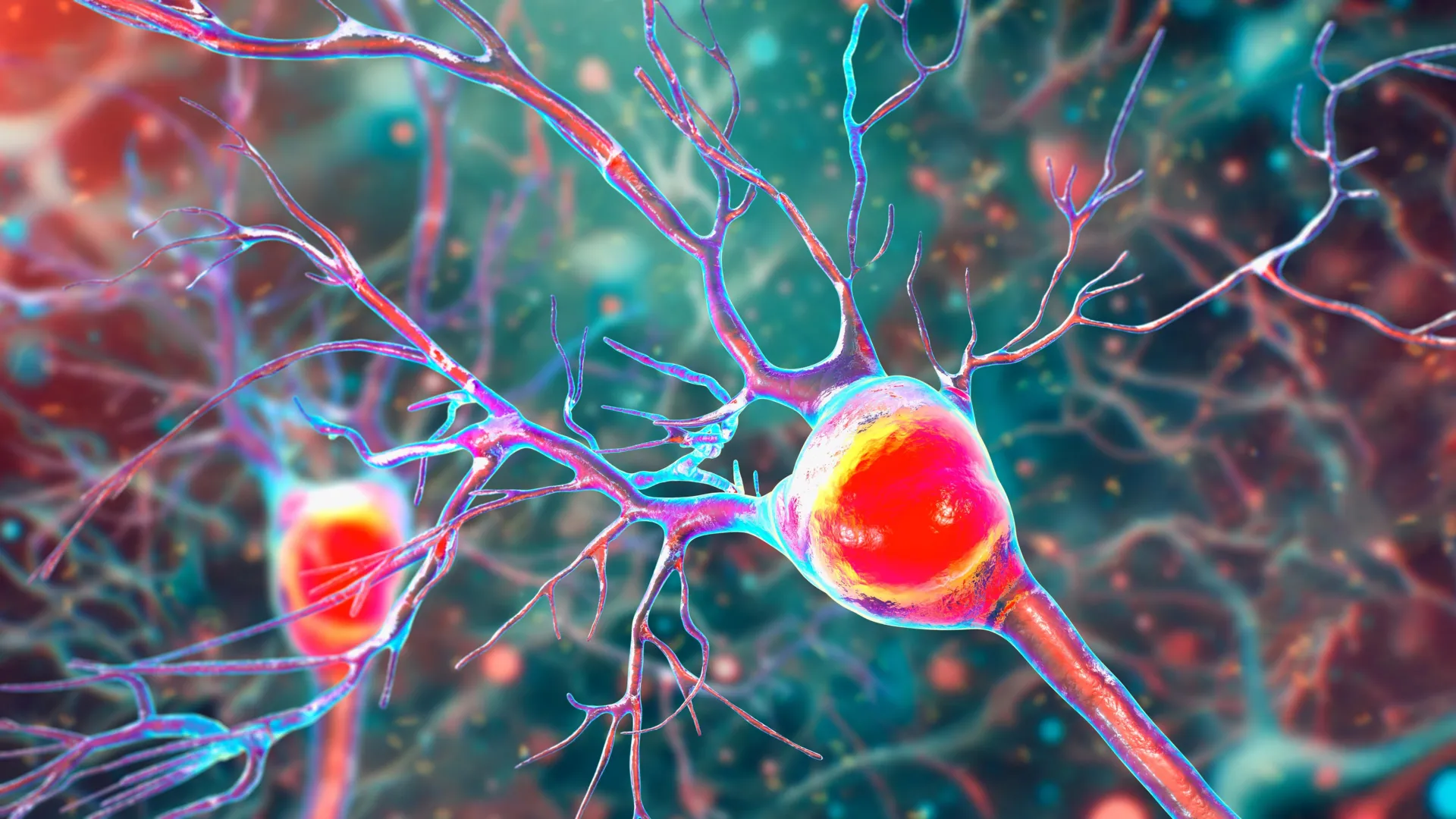

At its core, MS is defined by persistent inflammation and the progressive erosion of myelin, the vital protective sheath that ensheathes nerve fibers throughout the brain and spinal cord. This demyelination process severely impedes the efficient transmission of electrochemical signals along neural pathways, thereby disrupting the seamless flow of information essential for all neurological functions. Concurrently, mitochondria, often referred to as the cellular powerhouses, bear a distinct yet equally crucial responsibility: they are the primary generators of cellular energy, fueling the myriad biochemical processes necessary for cell survival and function.

The research team, under the guidance of Professor Seema Tiwari-Woodruff from the UC Riverside School of Medicine, posits that the inflammatory and demyelinating processes characteristic of MS within the cerebellum significantly disrupt mitochondrial function. This disruption, in turn, precipitates neuronal damage and the subsequent loss of Purkinje cells. Notably, the study observed a marked reduction in COXIV, a crucial mitochondrial protein, within demyelinated Purkinje cells. This finding strongly suggests that impaired mitochondrial capacity directly contributes to cell demise and the degenerative changes observed in the cerebellum.

The paramount importance of Purkinje cells cannot be overstated when considering the complexities of motor control. The seemingly effortless execution of everyday actions, from ambulation to grasping an object or maintaining upright posture, hinges upon a finely tuned symphony of collaboration between muscles, sensory feedback systems, and various brain regions, with the cerebellum playing a pivotal coordinating role. Within this vital structure reside Purkinje neurons, large and highly metabolically active cells that are indispensable for orchestrating smooth, precise, and fluid movements. Their integrity is fundamental for activities ranging from athletic endeavors to the most basic acts of locomotion and fine motor skill execution.

In the context of MS and other neurodegenerative conditions affecting the cerebellum, damage to these crucial neurons often culminates in their gradual demise. As Purkinje cells are lost, individuals may develop ataxia, a debilitating condition characterized by profound deficits in coordination and a marked instability of movement. Analysis of cerebellar tissue from individuals with MS revealed significant pathological alterations in these neurons, including dendritic arborization loss, myelin sheath degradation, and critically, mitochondrial dysfunction, signifying a profound energy crisis within the cells. Given their central role in motor execution, the attrition of Purkinje cells directly translates into severe mobility impairments. Elucidating the precise mechanisms driving their damage in MS holds the key to developing more effective interventions aimed at preserving motor function and balance.

To gain a deeper understanding of the temporal dynamics of these cellular changes, the researchers employed experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a widely utilized animal model that recapitulates key features of MS. This model allowed for the longitudinal observation of mitochondrial alterations as the disease progressed in a controlled environment. The EAE mice exhibited a consistent decline in Purkinje cell numbers, mirroring the pathological findings in human MS.

The study revealed that surviving neurons in the affected mice became increasingly dysfunctional as their mitochondria, the engines of cellular energy production, began to falter. Moreover, the research observed an early onset of myelin breakdown, suggesting that a confluence of factors—energy deprivation, myelin loss, and neuronal compromise—initiates the pathological cascade early in the disease process, with overt cell death occurring at later, more severe stages. The pervasive energy deficit within brain cells appears to be a central determinant of the damage inflicted by MS. While the EAE model does not perfectly replicate every facet of human MS, its considerable overlap with the human condition renders it an invaluable resource for dissecting neurodegenerative mechanisms and evaluating novel therapeutic strategies.

The insights gleaned from this research offer critical perspectives on the pathogenesis of cerebellar dysfunction in MS. The findings strongly suggest that interventions aimed at bolstering mitochondrial health could represent a promising avenue for slowing or even preventing neurological decline, thereby enhancing the quality of life for individuals navigating the challenges of MS. This work represents a significant stride toward unraveling the intricate molecular underpinnings of MS and paving the way for the development of more targeted and efficacious treatments for this profoundly debilitating disease.

Future research endeavors are poised to investigate whether mitochondrial dysfunction extends beyond Purkinje cells to encompass other critical cerebellar cell populations, including oligodendrocytes, which are responsible for myelin formation and maintenance, and astrocytes, which provide essential support to neuronal networks. Answering this question will involve focused studies examining mitochondrial health within these specific cell types in the cerebellum. Such investigations hold the potential to identify strategies for early brain protection, such as augmenting cellular energy levels, facilitating myelin repair, or modulating the immune response before irreversible damage occurs. This proactive approach is particularly vital for individuals with MS experiencing balance and coordination difficulties, symptoms directly attributable to cerebellar pathology.

Professor Tiwari-Woodruff underscored the indispensable role of sustained investment in scientific research, emphasizing that any reduction in funding for scientific exploration inevitably decelerates progress at precisely the moments when it is most urgently needed. Public support for research, she contends, is more critical now than ever before.

The research collaboration involved Professor Tiwari-Woodruff and graduate student Kelley Atkinson, alongside Shane Desfor, Micah Feria, Maria T. Sekyia, Marvellous Osunde, Sandhya Sriram, Saima Noori, Wendy Rincó, and Britany Belloa. The study meticulously analyzed postmortem cerebellar tissue obtained from individuals diagnosed with secondary progressive MS, comparing these samples with those from healthy control subjects. The crucial tissue samples were generously provided by the National Institutes of Health’s NeuroBioBank and the Cleveland Clinic. Financial support for this pivotal research was provided by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The comprehensive findings are detailed in the research paper titled "Decreased mitochondrial activity in the demyelinating cerebellum of progressive multiple sclerosis and chronic EAE contributes to Purkinje cell loss."