The intricate dance between viruses and their host cells dictates the trajectory and severity of an infection, with the efficiency of viral dissemination playing a pivotal role in determining pathogenic outcomes. Recent groundbreaking research, published in the esteemed journal Science Bulletin, has unveiled a previously unrecognized mechanism employed by viruses to propagate rapidly and aggressively within an organism. A collaborative team of scientists, spearheaded by investigators from Peking University Health Science Center and the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, has identified a novel cellular conduit that fundamentally alters our understanding of viral spread, dubbing these unique structures "Migrions."

Traditional models of viral transmission largely focus on the release of individual viral particles, either passively into the extracellular space or actively through budding, to infect neighboring or distant cells. However, this new discovery introduces a paradigm shift, demonstrating that viruses can actively commandeer specific cellular machinery to facilitate their movement. The research specifically highlights the exploitation of migrasomes, dynamic cellular structures that emerge during cell migration. These structures are not merely passive carriers; they represent a sophisticated viral strategy for enhanced proliferation.

Migrasomes themselves are fascinating entities, relatively recently characterized in cellular biology. They are distinct, bleb-like protrusions formed at the trailing edge of migrating cells, interconnected by thin retraction fibers. Their primary physiological role is thought to involve the deposition of extracellular matrix components and the removal of cellular waste, influencing tissue remodeling and cell-cell communication. The groundbreaking finding was that in cells infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a well-established model rhabdovirus, viral genetic material and essential proteins were observed to be deliberately and efficiently packaged into these migrasomes. This active loading process signifies a targeted manipulation by the virus, rather than an incidental encapsulation of viral components.

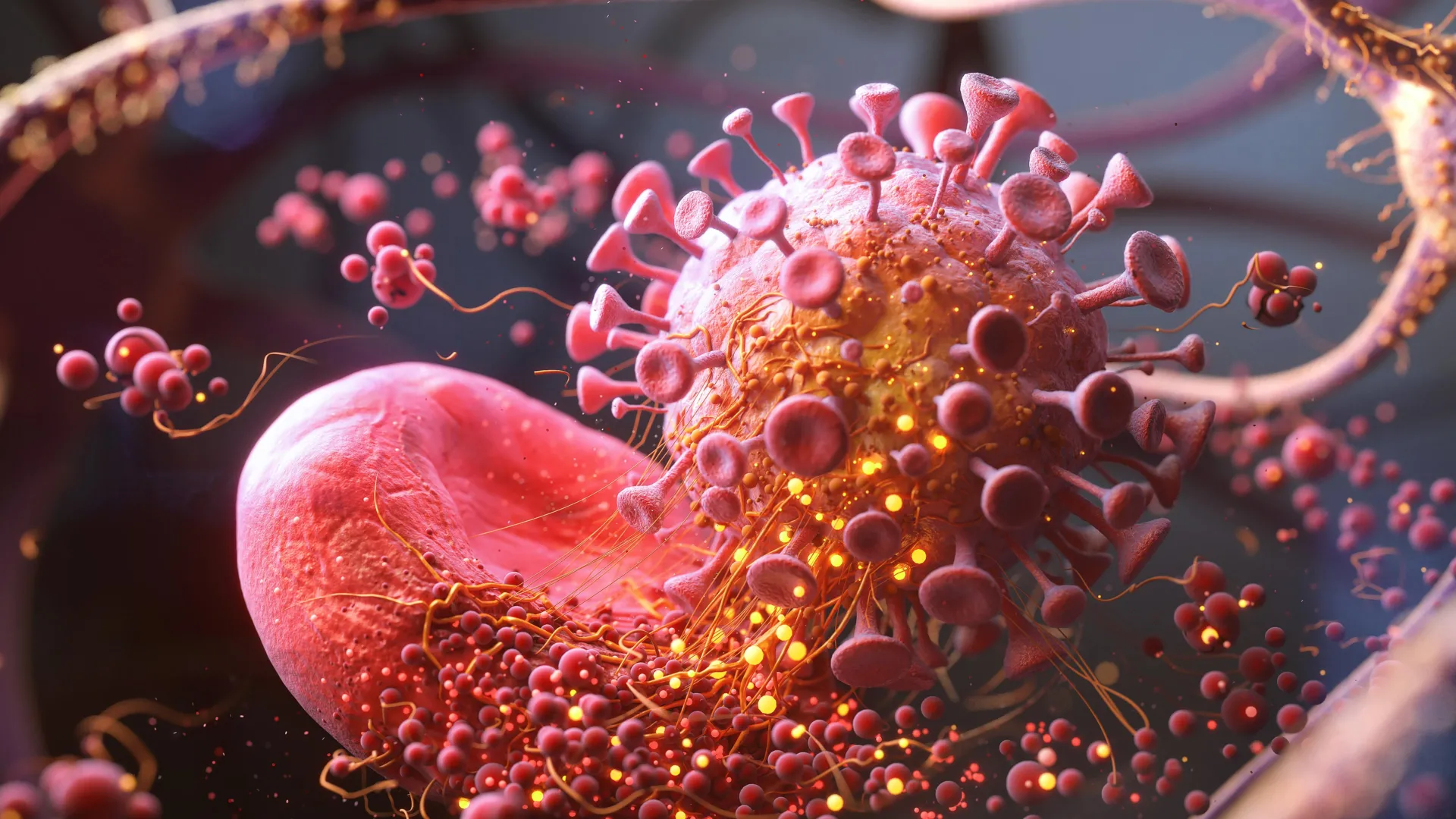

Crucially, the researchers identified a subset of these virus-laden migrasomes that exhibited a distinct, virus-like architecture. These specialized structures, termed "Migrions," were characterized by the presence of viral nucleic acids encapsulated within, while simultaneously displaying the viral surface glycoprotein VSV-G on their outer membrane. This hybrid composition—part host cell structure, part viral machinery—marks Migrions as a novel form of viral transport. Unlike free-floating VSV particles, which are standalone infectious units, Migrions are chimeric entities, leveraging both cellular architecture and viral proteins to achieve their infectious potential. This distinction is critical, as it implies a different biogenesis and potentially a different set of interactions with target cells compared to conventional virions or even other forms of extracellular vesicles (EVs).

One of the most profound implications of this discovery lies in the accelerated replication kinetics observed in newly infected cells. When viruses are delivered via Migrions, rather than as individual virions, they replicate at a significantly faster rate. This enhanced growth is attributed to the Migrion’s capacity to simultaneously deliver multiple copies of the viral genome into a single target cell. In typical viral infection, a single virion delivers one or a few copies of its genome, initiating a sequential replication cycle. With Migrions, the synchronous delivery of numerous genetic blueprints allows for parallel replication to commence immediately upon entry, effectively supercharging the initial phase of infection and rapidly amplifying the viral load within the host. This immediate head start dramatically shortens the time required for the virus to establish a robust foothold and disseminate further.

Furthermore, the study illuminated another remarkable characteristic of Migrions: their potential to carry more than one type of virus simultaneously. This multi-viral payload capability sets Migrions apart from most traditional extracellular vesicle-mediated viral spread mechanisms, which are often highly specific to a single viral species or genotype. The capacity for co-transmission suggests a novel avenue for viral evolution, recombination, and the emergence of new pathogenic strains. If two different viruses or viral variants can be delivered to the same cell via a single Migrion, it could significantly increase the chances of genetic reassortment or complementation, potentially leading to altered tropism, enhanced virulence, or even resistance to antiviral therapies. This aspect opens up entirely new avenues for understanding viral ecology and the dynamics of co-infections.

The mechanism by which Migrions engage and enter new cells also presents notable differences from conventional viral entry. Unlike many viruses that rely on highly specific cell surface receptors for attachment and entry, Migrions appear to enter target cells primarily through endocytosis, a common cellular uptake pathway, without stringent receptor specificity. This broadens the potential range of cells that Migrions can infect, making the transmission route more versatile. Once internalized within the endosomal compartments of the recipient cell, the acidic environment characteristic of these vesicles plays a crucial role. This low pH condition triggers a conformational change in the VSV-G protein displayed on the Migrion surface, activating its fusogenic properties. This activation is essential, as it mediates the fusion of the Migrion membrane with the endosomal membrane, subsequently releasing the viral contents directly into the host cell’s cytoplasm. This critical step bypasses lysosomal degradation and allows the viral genetic material to access the cellular machinery necessary for replication, ensuring the successful initiation of a new infection cycle.

To validate the clinical relevance and pathogenic potential of this newly discovered transmission route, the research team conducted in vivo experiments using animal models. Mice exposed to Migrion-mediated infection demonstrated a dramatically increased infectivity compared to those exposed to equivalent amounts of free virus particles. The consequences of Migrion-facilitated infection were stark: animals developed significantly more severe disease manifestations, including profound infections in vital organs such as the lungs and brain. The neurological involvement, characterized by severe encephalitis, was particularly pronounced and frequently culminated in fatality. These grim outcomes underscore the enhanced pathogenic potential of Migrions, suggesting that this mechanism not only accelerates viral spread but also contributes substantially to the overall morbidity and mortality associated with viral diseases. The severity observed in these models highlights the critical need to further investigate this pathway in human pathology.

This groundbreaking research compels the scientific community to fundamentally rethink existing paradigms of viral dissemination within a host. The concept of "Migrion," described as a chimeric structure forged between viral components and a host migrasome, introduces an entirely novel model of intercellular viral transmission. For decades, assumptions about viral propagation have largely centered on passive diffusion, direct cell-to-cell spread through synapses or gap junctions, or dissemination via the circulatory or lymphatic systems as free virions. By establishing a direct link between viral spread and host cell migration, this mechanism challenges these long-standing tenets. It implies that viruses are not merely passengers in the body but active manipulators of cellular processes, exploiting the host’s own migratory machinery to move efficiently and systemically through tissues.

This migration-dependent strategy offers a fresh perspective on how certain infections can escalate with such alarming rapidity and severity. Instead of relying solely on the passive release of virions into the surrounding tissue fluids, viruses can effectively hitchhike on actively moving cells or utilize the migrasomes they shed, potentially bypassing cellular barriers or reaching distant sites more effectively. Such a mechanism could explain the rapid systemic dissemination observed in some highly aggressive viral infections, leading to swift onset of severe symptoms and multi-organ involvement. Understanding this sophisticated viral exploitation of host cell biology not only enriches our knowledge of viral pathogenesis but also opens up promising new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Targeting the formation of Migrions, their release, or their entry into new cells could represent an innovative strategy for developing next-generation antiviral therapies, aiming to curb infection spread and mitigate disease severity in the future. Further research will undoubtedly delve deeper into the specific molecular cues that govern Migrion formation and release, paving the way for targeted pharmaceutical strategies.