A groundbreaking study utilizing a meticulously controlled rat population has illuminated a previously underappreciated aspect of gut microbiome development: the influence of an individual’s genetic makeup extends beyond their own biological code, actively shaping the microbial communities of their cage mates. This research, published in the esteemed journal Nature Communications, challenges conventional understandings by demonstrating that genetic predispositions can propagate through social interactions, fundamentally altering the microbial ecosystems within an organism.

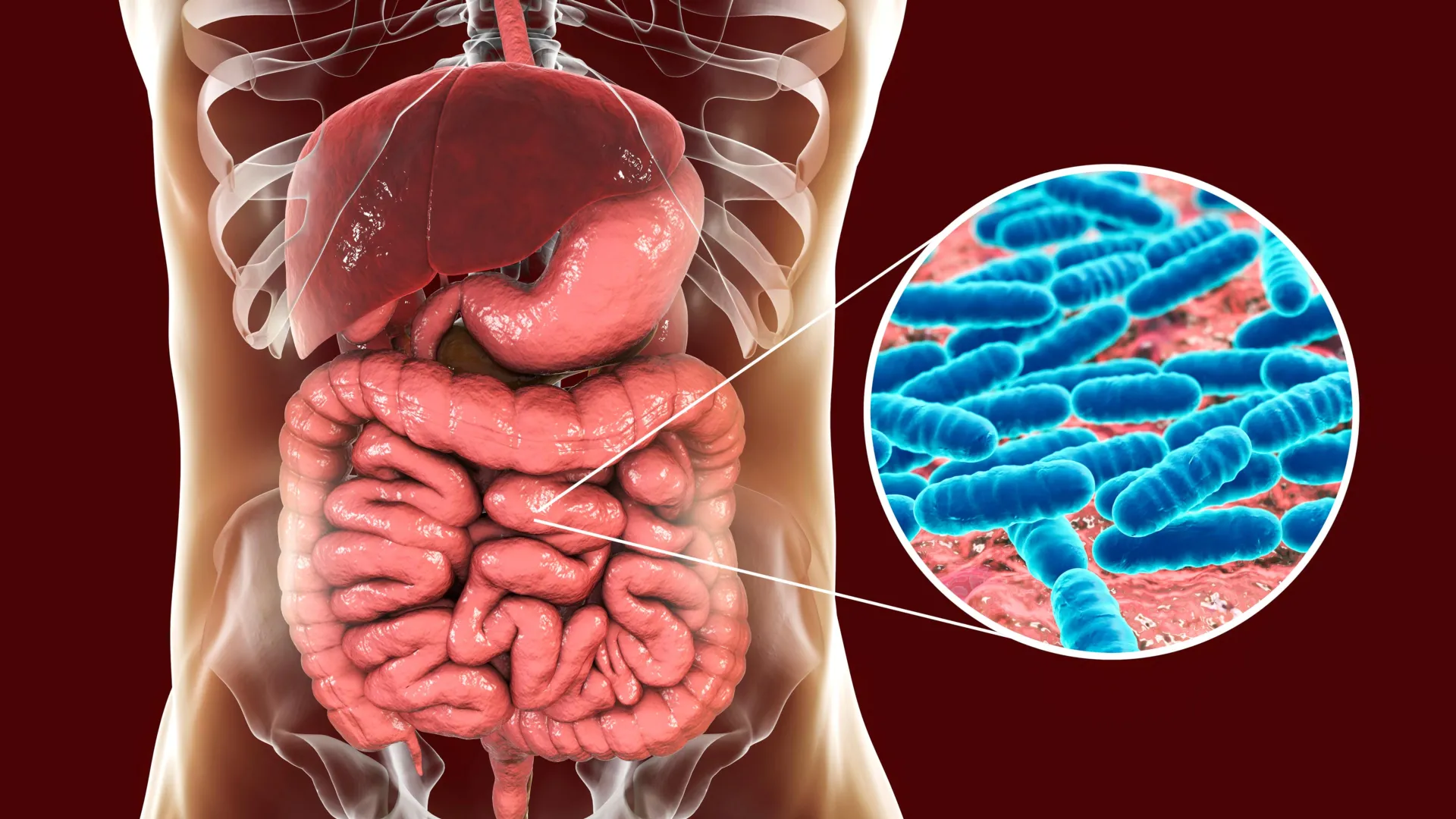

The investigation delved into the intricate interplay between genetics and the trillions of microorganisms residing in the digestive tracts of more than 4,000 rats, revealing that the composition of this internal ecosystem is not solely determined by an individual’s inherent genetic blueprint. Instead, the genetic profile of cohabiting individuals exerts a significant, measurable impact. This finding introduces a novel paradigm in the study of genetics and social behavior, proposing a tangible pathway through which genetic influences can "spill over" from one organism to another. While genes themselves are immutable and remain localized within an individual, the microbial passengers they influence are highly mobile. The study’s core revelation is that specific genetic traits can foster the proliferation of particular gut bacteria, which then have the capacity to spread through close physical proximity and shared environments.

Dr. Amelie Baud, a senior researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and a principal investigator on the study, articulated the significance of this discovery, stating, "This phenomenon is not a matter of chance, but rather a demonstrable consequence of genetic predispositions extending their reach to others via social contact. Genes indeed sculpt the gut microbiome, and our findings underscore that the genetic landscape of those around us plays a crucial role."

For decades, the gut microbiome has been recognized as a vital component of overall health, playing indispensable roles in digestion, nutrient absorption, immune system regulation, and even influencing mood and behavior. While external factors such as diet and pharmaceutical interventions are well-established modulators of these microbial communities, deciphering the precise contribution of host genetics has remained a considerable scientific challenge. In humans, definitive genetic links to specific gut bacteria have been sparse, with only two genes consistently identified: the lactase gene, which dictates lactose digestion and consequently influences milk-metabolizing microbes, and the ABO blood group gene, whose impact on gut bacteria, while observed, remains mechanistically enigmatic.

Scientists have long suspected that numerous other gene-microbe associations exist, but their identification has been hampered by the pervasive overlap of genetic and environmental factors in everyday life. An individual’s genes can subtly influence their dietary habits and lifestyle choices, which in turn shape their microbiome. Simultaneously, human populations, particularly within families and close social circles, often share food, living spaces, and even microbial species, creating a complex web that makes it exceptionally difficult to disentangle innate predispositions from learned behaviors and environmental exposures.

To circumvent these inherent complexities, the research team, a collaboration between the Centre for Genomic Regulation and the University of California San Diego, strategically employed rats as their model organism. Rats share a remarkable degree of biological similarity with humans, particularly concerning their mammalian physiology, and crucially, they can be maintained under rigorously controlled experimental conditions, including the administration of identical diets across all subjects.

The experimental design involved a diverse cohort of rats, each possessing a unique genetic profile, organized into four distinct groups. These groups were housed in separate facilities across the United States, adhering to varied husbandry protocols. This distributed housing strategy was designed to rigorously test the robustness and consistency of genetic effects on the microbiome across different environmental contexts.

By integrating comprehensive genetic data with detailed microbiome profiles from all 4,000 participating rats, the research team was able to pinpoint three distinct genetic regions that consistently and significantly influenced the composition of gut bacteria, irrespective of the environmental variations. The most pronounced association identified involved the St6galnac1 gene, which is responsible for the addition of specific sugar molecules to the mucus lining of the gut. This gene demonstrated a strong correlation with elevated levels of Paraprevotella, a genus of bacteria believed to thrive on these sugar-rich mucins. This particular gene-microbe link was observed with remarkable consistency across all four experimental cohorts.

A second significant genetic region encompassed several mucin genes, which are critical for the formation and maintenance of the gut’s protective mucus layer. This region was found to be associated with an increased abundance of bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes phylum. The third genetic locus of interest contained the Pip gene, which encodes an antibacterial molecule, and its influence was linked to bacteria within the Muribaculaceae family. This bacterial family is prevalent in rodent populations and has also been detected in the human gut microbiome.

The substantial sample size of this study afforded researchers an unprecedented opportunity to quantitatively estimate the relative contributions of an individual rat’s own genes versus the genes of its social partners to the makeup of its gut microbiome. This concept, often referred to as indirect genetic effects, is familiar in other biological contexts, such as a mother’s genes influencing her offspring’s development through the maternal environment she provides. However, this study applied the principle to a novel arena: the microbial communities of non-reproductive social partners.

Within the highly controlled experimental setup, researchers were able to isolate and examine indirect genetic effects in this unique context. They developed a sophisticated computational model that effectively disentangled the direct genetic influence of a rat on its own gut microbes from the indirect influence exerted by its cage mates’ genes. The analysis revealed that the population dynamics of certain Muribaculaceae bacteria were shaped by both direct genetic contributions and these indirect, socially mediated genetic effects, providing compelling evidence that specific genetic influences can indeed propagate through the exchange of microbes.

When these newly identified social effects were incorporated into their statistical models, the overall estimated genetic influence on the three identified gene-microbe links saw a substantial amplification, increasing by a factor of four to eight times. The researchers themselves acknowledge that this figure may still represent an underestimation of the true extent of genetic influence. "We have likely only scratched the surface of this phenomenon," Dr. Baud commented. "These are the microbial associations where the genetic signal is strongest, but it is plausible that a far greater number of microbes are influenced once we develop more refined microbiome profiling technologies."

The findings elucidate a biological mechanism through which genetic effects originating from one individual can disseminate through social networks via the transmission of gut microbes, thereby modifying the physiology of others without any alteration to their fundamental DNA. If analogous processes are operative in human populations, and given the mounting evidence linking the gut microbiome to a wide array of health outcomes, it is conceivable that the impact of genetic factors on human health may be significantly underestimated in large-scale population studies. Consequently, an individual’s genetic makeup could influence not only their personal susceptibility to diseases but also the disease risk profiles of those in their immediate social sphere.

The implications of these findings for human health are far-reaching. Dr. Baud highlighted the established connections between the microbiome and critical physiological systems, including immune function, metabolic processes, and even behavioral patterns. However, many observed correlations between the microbiome and health conditions have lacked clear causal mechanisms, often leaving the underlying biological pathways obscured. The current study, by employing genetically diverse animal models within controlled environments, offers a powerful approach to move beyond mere correlation towards testable hypotheses that can illuminate the intricate mechanisms of gene-microbe interactions in health and disease.

The research team pointed to a compelling parallel between the rat gene St6galnac1 and the human gene ST6GAL1. These genes are functionally homologous and ST6GAL1 has previously been implicated in studies involving Paraprevotella in humans. This suggests that the conserved mechanism by which animals glycosylate their gut mucus – the process of adding sugar molecules – might be a key determinant in dictating which microbial species can successfully colonize and thrive within the digestive system, potentially representing a shared evolutionary pathway across species.

Furthermore, the researchers explored the potential relevance of this mechanism to infectious diseases, including COVID-19. Previous research has linked variations in the human ST6GAL1 gene to an increased risk of breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, even in vaccinated individuals. Paraprevotella has also been observed to facilitate the breakdown of digestive enzymes that the virus utilizes to gain entry into host cells. Based on these observations, the researchers hypothesize that genetic variations in ST6GAL1 could modulate the abundance of Paraprevotella, thereby influencing an individual’s susceptibility to viral infections.

Additionally, the study posits a potential link to IgA nephropathy, an autoimmune kidney disease. Paraprevotella has the capacity to alter Immunoglobulin A (IgA), an antibody crucial for mucosal immunity that normally serves to protect the gut lining. When altered by microbial activity, IgA can translocate into the bloodstream and aggregate, forming immune complexes that can damage the kidneys – a hallmark characteristic of IgA nephropathy.

The next phase of this research will involve a detailed examination of how the St6galnac1 gene specifically influences Paraprevotella populations in rats and the cascade of downstream effects that this interaction triggers within the gut and subsequently throughout the entire organism. "This bacterium has become a particular focus of my research," Dr. Baud enthused. "The robustness of our findings, supported by data from four independent research facilities, offers a unique foundation for follow-up investigations in any experimental setting. The strength of these associations, when compared to most previously reported host-microbiome links, is truly remarkable, presenting an exceptional opportunity for further scientific exploration."