A groundbreaking scientific investigation has unveiled a previously unacknowledged threat to human health, revealing that a significant number of everyday synthetic chemicals, pervasive in our environment, food, and water, actively impair the beneficial bacteria residing within the human gut. This comprehensive laboratory analysis challenges long-held assumptions about chemical inertness, demonstrating that 168 distinct compounds out of over a thousand tested possess the capacity to either inhibit or halt the proliferation of crucial microbial species essential for a healthy digestive system and overall physiological function. The findings suggest a critical oversight in current chemical safety assessments, demanding a fundamental re-evaluation of how industrial and agricultural substances are developed, regulated, and understood in relation to human biology.

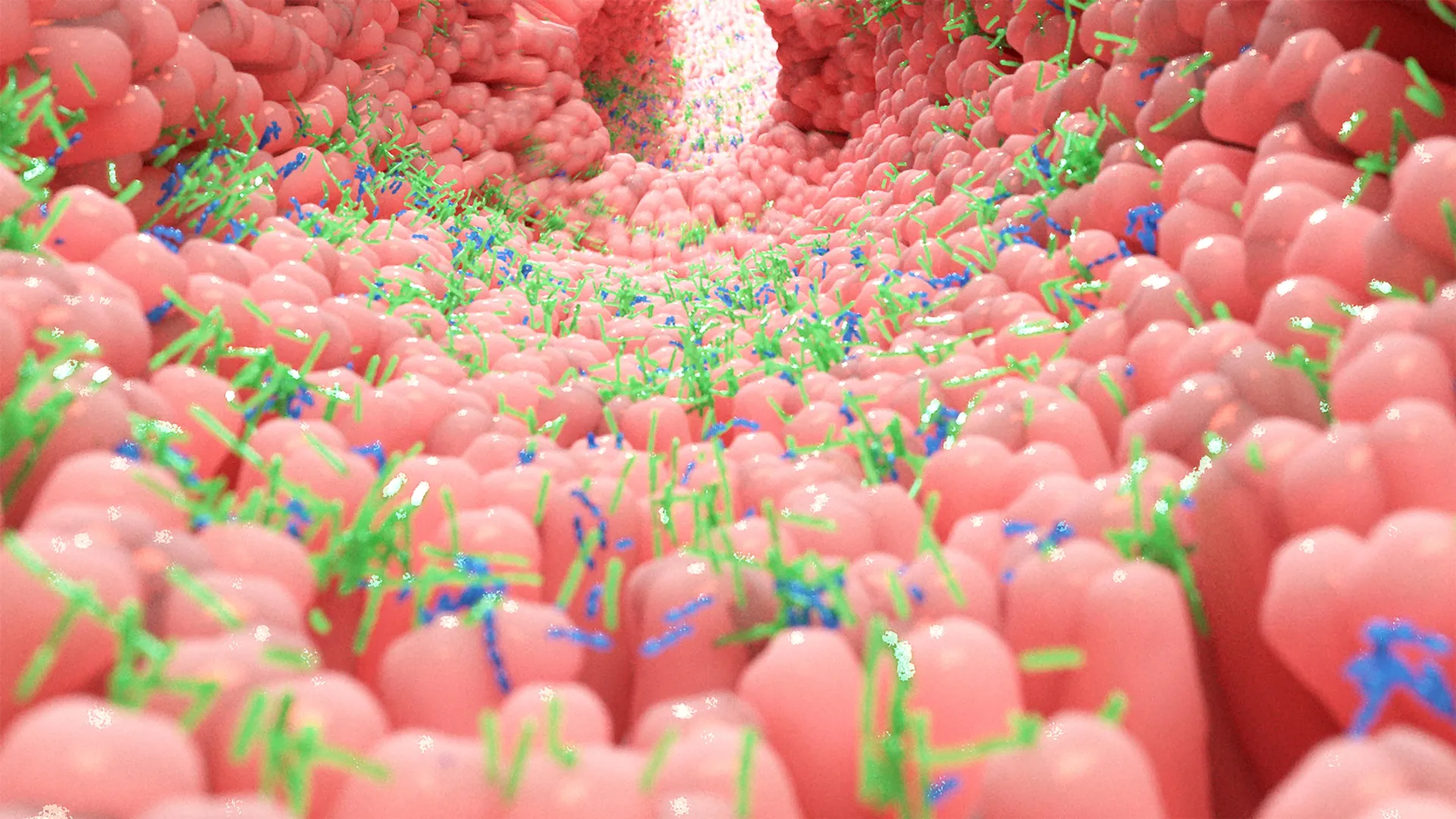

The human gut, often referred to as the "second brain" or a vast internal ecosystem, hosts trillions of microorganisms collectively known as the gut microbiome. This intricate community, comprising approximately 4,500 different bacterial species, plays an indispensable role in maintaining health. Far from being passive inhabitants, these microbes are actively involved in a myriad of vital bodily processes. They aid in the digestion and absorption of nutrients, synthesize essential vitamins like B and K, and help break down dietary fibers that the human body cannot process on its own. Beyond digestive functions, a robust and diverse gut microbiome is intimately linked to a strong immune system, influencing the body’s ability to ward off pathogens and regulate inflammatory responses. Emerging research also highlights its profound impact on mental well-being through the gut-brain axis, influencing mood, cognitive function, and even susceptibility to neurological conditions. Disruptions to this delicate balance, known as dysbiosis, have been increasingly implicated in a wide spectrum of chronic health issues, ranging from gastrointestinal disorders like irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease to obesity, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune conditions, and even certain neurodegenerative diseases.

One of the most alarming implications of this new research is the discovery that exposure to these environmental pollutants can inadvertently contribute to the escalating global crisis of antibiotic resistance. The study observed that when beneficial gut bacteria are subjected to these chemical stressors, they can undergo adaptive changes in their functional mechanisms as a survival strategy. In a particularly concerning subset of cases, these adaptations inadvertently conferred resistance to potent antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic commonly used to treat severe bacterial infections. Should similar mechanisms occur within the complex environment of the human body, the efficacy of vital antimicrobial treatments could be further compromised, making common infections significantly more challenging, if not impossible, to treat. This phenomenon adds another layer of complexity to the already urgent public health threat posed by drug-resistant superbugs, suggesting that environmental chemical contamination might be an unrecognized driver of this critical issue.

The exhaustive study, spearheaded by a team of researchers at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit, involved the meticulous testing of 1076 different chemical contaminants against 22 representative species of gut bacteria. These bacteria were carefully selected to represent the broad diversity and crucial functions of the human gut microbiome. Conducted under stringent laboratory conditions, the analysis provided a controlled environment to precisely measure the impact of each chemical on microbial growth and viability. This large-scale, systematic approach allowed for the identification of a substantial number of compounds whose effects on gut flora had previously gone undetected or unexamined.

Among the chemicals identified as particularly detrimental to gut bacteria were various pesticides, a broad category encompassing herbicides and insecticides that are widely applied in agricultural settings to protect crops from pests and weeds. These substances, designed to be biologically active against specific target organisms, demonstrate an alarming off-target toxicity to non-target microbial species crucial for human health. Beyond agricultural chemicals, industrial compounds also featured prominently on the list of harmful substances. These include flame retardants, chemicals integrated into a vast array of products from furniture to electronics to reduce flammability, and plasticizers, additives that enhance the flexibility and durability of plastics found in countless consumer goods, food packaging, and building materials. The widespread presence of these compounds in our daily lives underscores the pervasive nature of potential exposure, making the study’s findings particularly relevant to public health.

A fundamental issue highlighted by this research lies in the inherent limitations of current chemical safety evaluation protocols. Historically, the regulatory frameworks for assessing the safety of new chemicals have largely focused on their direct toxicity to human cells or specific organ systems, often overlooking the complex interplay with the gut microbiome. Chemicals are typically designed with highly specific targets in mind; for instance, an insecticide is developed to selectively harm insects, and its safety testing traditionally evaluates its impact on human physiology, not on the trillions of microorganisms within the human digestive tract. This reductionist approach, while effective for certain parameters, has created a significant blind spot. The assumption has often been that if a chemical does not directly harm human cells, it is safe, without considering its potential indirect effects via the disruption of the microbial communities upon which human health profoundly depends. This paradigm is now being fundamentally challenged by the emerging understanding of the microbiome’s central role.

In a forward-thinking move, the research team leveraged the extensive dataset generated from their experiments to develop an innovative machine learning model. This artificial intelligence-driven tool is designed to predict whether both existing industrial chemicals and those currently under development are likely to exert harmful effects on human gut bacteria. The development of such a predictive model marks a significant step towards proactive chemical safety, offering the potential to screen vast numbers of compounds rapidly and cost-effectively, steering away from substances that pose risks to the microbiome even before they are widely introduced. This predictive capability aligns with the ambitious goal of moving towards a future where chemicals are "safe by design," incorporating microbiome compatibility as a core criterion from the earliest stages of development. The full findings of this landmark study, along with details of the machine learning model, were published in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature Microbiology.

The researchers involved in this pivotal study have issued a clear call for a paradigm shift in how chemical safety is conceived and regulated. Dr. Indra Roux, the study’s first author and a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit, expressed her surprise at the breadth and strength of the chemicals’ effects: "We’ve discovered that many compounds engineered to interact with specific biological targets, such as fungi or insects, also profoundly impact gut bacteria. What truly astonished us was the potency of these effects. For example, many industrial chemicals, like various flame retardants and plasticizers, which we encounter regularly and were generally considered biologically inert, actually exert significant effects on living organisms, specifically our microbial partners." Professor Kiran Patil, the senior author of the study and also based at the MRC Toxicology Unit, emphasized the transformative potential of their work: "The true strength of this extensive study lies in the wealth of data we now possess, which enables us to forecast the consequences of novel chemicals. Our ultimate objective is to usher in an era where new chemical formulations are intrinsically safe by their very design." Dr. Stephan Kamrad, another key contributor to the research, underscored the practical implications for regulatory bodies: "For any new chemical intended for human application, safety assessments must rigorously confirm their innocuousness towards our gut bacteria, given the inevitable routes of exposure through our food and water supply."

Despite these significant advancements, the scientific community acknowledges that there remain critical gaps in our understanding, particularly concerning the real-world impact of these chemical exposures. While the laboratory study conclusively demonstrates the potential for harm, precise information regarding the exact concentrations of these environmental chemicals that ultimately reach the human digestive system remains elusive. The researchers highlight the urgent need for future studies to track chemical exposure pathways throughout the human body, moving beyond isolated laboratory observations to assess cumulative and long-term effects in diverse populations. Professor Patil articulated this necessity: "Having initiated the discovery of these interactions in a controlled laboratory environment, the crucial next step is to gather more comprehensive real-world chemical exposure data to ascertain if analogous effects are manifesting within human bodies."

Until a more complete picture of real-world exposure and its precise health implications emerges, the researchers recommend several practical, albeit limited, steps individuals can take to minimize their personal exposure to these pervasive chemicals. These include thoroughly washing fruits and vegetables before consumption to remove pesticide residues and avoiding the use of synthetic pesticides in home gardens. While these individual actions offer a degree of mitigation, the broader message from this landmark study is a compelling call for systemic change. It underscores the urgent need for regulatory bodies, industrial manufacturers, and policymakers worldwide to integrate microbiome health into all future chemical development and safety evaluations, fostering a healthier environment for both human and microbial life.