In a significant stride towards more refined cancer treatments, a collaborative research endeavor spearheaded by scientists at RMIT University has unveiled a groundbreaking approach utilizing microscopic particles to selectively eradicate malignant cells. These innovative constructs, termed nanodots, are formulated from a metal-based compound and exhibit a remarkable capacity to induce self-destruction in cancerous tissue while largely preserving the integrity of healthy surrounding cells. This discovery, though currently in its nascent stages of development, holds profound implications for the future of oncology, potentially mitigating the severe systemic side effects often associated with conventional therapeutic modalities.

The pervasive challenge in cancer therapy has long been the elusive quest for specificity. Traditional treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation, operate on a principle of broad cellular toxicity, attacking rapidly dividing cells indiscriminately. While effective in combating tumors, this lack of selectivity inevitably leads to collateral damage to healthy, fast-replicating cells throughout the body, manifesting as debilitating side effects ranging from hair loss and nausea to severe immune suppression and organ damage. The advent of targeted therapies has sought to address this by focusing on specific molecular pathways or markers unique to cancer cells. However, even these approaches can encounter resistance or affect non-target cells sharing similar molecular characteristics. The RMIT team’s work introduces a distinct paradigm, leveraging inherent vulnerabilities within cancer cells themselves to trigger their demise, a strategy that could usher in an era of truly precise and gentle oncological intervention.

Central to this promising development are the nanodots themselves, meticulously engineered from molybdenum oxide. Molybdenum, a rare yet widely utilized transition metal, is a cornerstone in various industrial applications, particularly in electronics and as an alloying agent to enhance the strength and corrosion resistance of steel. Its oxide form, when precisely manipulated at the nanoscale, exhibits extraordinary chemical properties. According to Professor Jian Zhen Ou, the lead researcher from RMIT’s School of Engineering, and Dr. Baoyue Zhang, their investigations revealed that subtle alterations to the nanodots’ intricate chemical architecture empowered them to generate and release reactive oxygen molecules. These highly unstable oxygen species, commonly known as Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), are notorious for their ability to inflict damage upon vital cellular components, including DNA, proteins, and lipids, ultimately culminating in cellular dysfunction and, crucially, programmed cell death, or apoptosis.

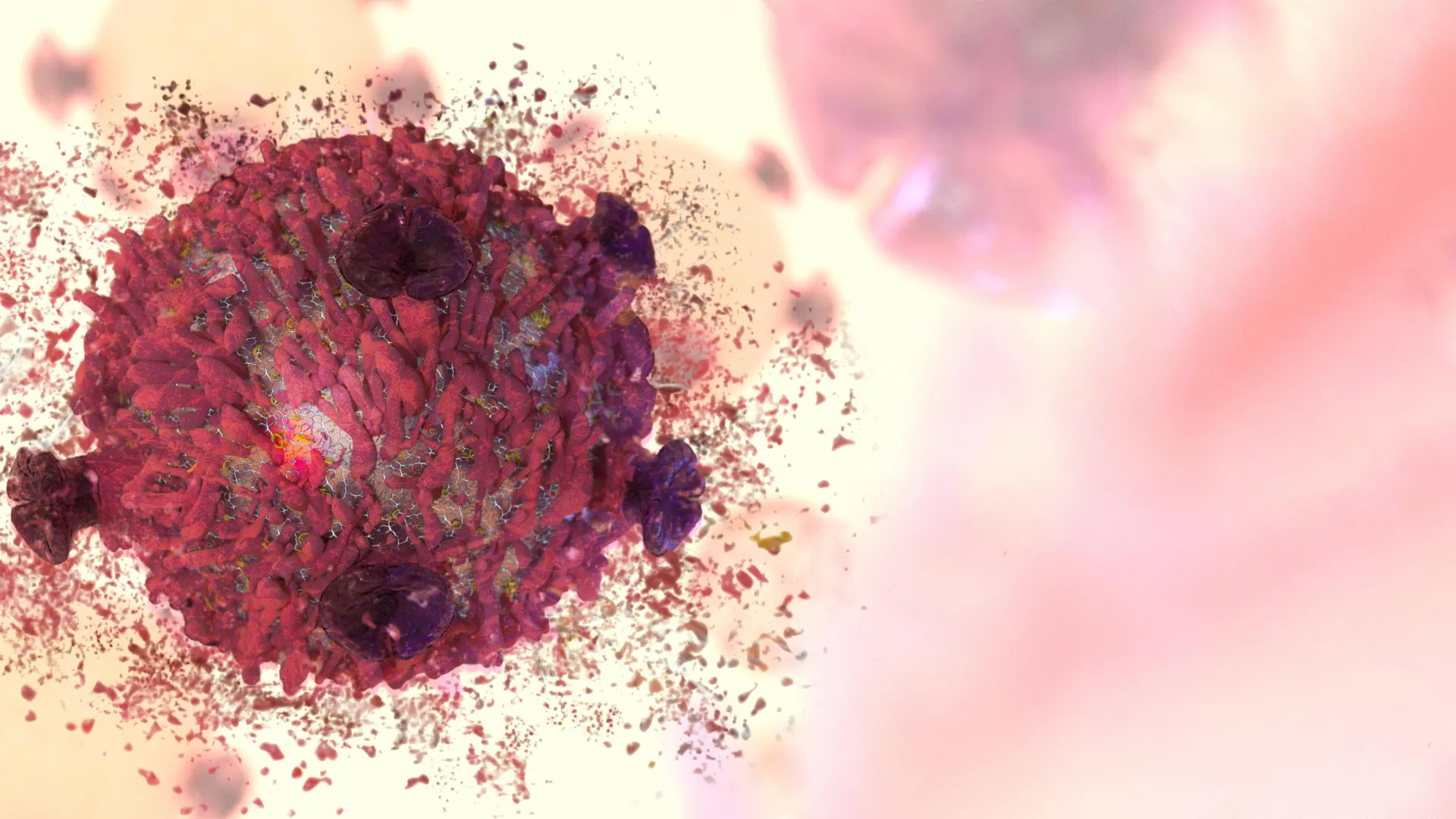

The mechanism by which these molybdenum oxide nanodots achieve their selective toxicity is elegantly rooted in the intrinsic biological differences between healthy and cancerous cells. Malignant cells typically exhibit a heightened metabolic rate, rapid proliferation, and often operate under conditions of increased cellular stress, including elevated levels of endogenous oxidative stress. This pre-existing state renders them more susceptible to additional oxidative burdens. As Dr. Zhang elucidated, "Cancer cells already navigate a higher baseline of stress compared to their healthy counterparts. Our particles effectively amplify this existing stress just enough to tip the balance, initiating a self-destruct sequence in the cancer cells, while normal cells, with their greater resilience, are able to adapt and cope without harm." This targeted amplification of oxidative stress, pushing cancer cells beyond their compensatory capacity, represents a sophisticated method of exploitation, turning a cellular vulnerability into a therapeutic advantage.

In rigorous laboratory experiments, the efficacy and selectivity of these nanodots were compellingly demonstrated. Researchers observed that the particles induced the demise of cervical cancer cells at a rate three times greater than that seen in healthy cells over a 24-hour incubation period. A particularly noteworthy characteristic of this technology is its independence from external light activation. Many existing nanoparticle-based therapies, especially those leveraging photodynamic effects, require exposure to specific wavelengths of light to activate their therapeutic payload. The ability of these molybdenum oxide nanodots to function effectively in complete darkness simplifies their potential application significantly, removing a considerable barrier to deep tissue penetration and broader clinical utility. Further underscoring their potent chemical reactivity, a separate experiment showed that the same nanodots could degrade a common blue dye by 90 percent within a mere 20 minutes, even without light, highlighting the intrinsic power of their oxidative generating capabilities.

The precision engineering of these nanodots involved an intricate process of fine-tuning their composition. The research team meticulously adjusted the metal oxide’s structure by introducing minute quantities of hydrogen and ammonium. This precise chemical modification was critical, as it fundamentally altered how the particles managed and transferred electrons. By facilitating a more efficient electron transfer process, the nanodots were enabled to generate significantly higher concentrations of reactive oxygen molecules. These molecules, once unleashed within the cellular environment, specifically target and overload the already stressed internal machinery of cancer cells, thereby triggering apoptosis. Apoptosis is a highly regulated and desirable form of cell death in therapeutic contexts, as it involves an organized dismantling of the cell without releasing harmful contents into the surrounding tissue, thus minimizing inflammation and collateral damage.

This groundbreaking research is a testament to the power of international scientific collaboration. The project brought together a diverse group of experts from multiple institutions, fostering an environment of shared knowledge and multidisciplinary innovation. Key contributors included Dr. Shwathy Ramesan from The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne, alongside researchers from Southeast University, Hong Kong Baptist University, and Xidian University in China. The crucial financial and infrastructural backing for this ambitious undertaking was provided by the ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs (COMBS), underscoring the importance of strategic investment in frontier scientific exploration. Such collaborative frameworks are increasingly vital in tackling complex biomedical challenges that demand a confluence of expertise across material science, chemistry, biology, and engineering.

While the preliminary findings from in vitro (laboratory-grown cell) experiments are undeniably encouraging, the scientific community recognizes that this represents merely the initial phase of a lengthy and rigorous development pathway. The transition from lab bench to clinical application is fraught with challenges and requires extensive validation. The immediate next steps for the COMBS research team at RMIT involve advancing the technology through preclinical studies, which will entail testing the nanodots in animal models. These in vivo studies are crucial for assessing the nanodots’ biocompatibility, systemic distribution, metabolism, efficacy in a complex biological system, and any potential long-term toxicity. Success in animal models would then pave the way for human clinical trials, a multi-phase process designed to evaluate safety, dosage, and ultimate therapeutic effectiveness in patients.

The broader implications of this research extend beyond the immediate promise of a new cancer treatment. The affordability and relative safety of manufacturing molybdenum oxide, compared to more costly and potentially toxic noble metals like gold or silver, present a significant advantage. This economic factor could contribute to making advanced cancer therapies more accessible globally, addressing a critical disparity in healthcare. Furthermore, the principles underlying this selective oxidative stress induction could potentially be adapted for treating a wider spectrum of cancers, or even other diseases characterized by cellular vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, the development of these molybdenum oxide nanodots by the RMIT-led team represents a pivotal moment in nanomedicine and oncology. By harnessing the inherent weaknesses of cancer cells and leveraging a common, affordable metal oxide, these researchers have opened a new avenue for developing highly targeted, less invasive, and potentially more effective cancer therapies. While the journey from laboratory discovery to widespread clinical application is often protracted and demanding, the initial results offer a compelling vision of a future where cancer treatment is not only more powerful but also significantly gentler on the human body, transforming the landscape of patient care. The scientific community eagerly anticipates the further progression of this innovative technology, hopeful that it will indeed contribute to a new generation of life-saving interventions.