In the rapidly evolving landscape of oncology, T-cell immunotherapy stands as a monumental leap forward, offering unprecedented hope to patients battling various malignancies. These sophisticated treatments harness the body’s own immune system, specifically its highly specialized T lymphocytes, to identify and eradicate cancerous cells. Despite their remarkable success in specific cancer types, a comprehensive molecular understanding of precisely how these therapies orchestrate their effects has remained elusive. This fundamental knowledge gap has significantly impeded the broader application of T-cell-based interventions, leaving a vast majority of cancers unresponsive to these otherwise potent treatments. Unlocking the intricate mechanisms governing T-cell activation is therefore paramount to extending the benefits of immunotherapy to a wider patient population.

Groundbreaking research conducted at The Rockefeller University has now shed critical light on the operational dynamics of the T-cell receptor (TCR), a complex protein structure integral to T-cell function and a central player in immunotherapeutic strategies. Scientists from the Laboratory of Molecular Electron Microscopy, employing advanced imaging techniques, have meticulously characterized the TCR in an environment closely mirroring its physiological cellular context. Their findings reveal a previously unrecognized conformational change within the TCR, describing it as a compact, quiescent entity that rapidly transitions to an open, extended configuration upon encountering a foreign or anomalous particle, such as an antigen. This revelation directly challenges earlier structural interpretations of the receptor, which had depicted it as perpetually extended even in its inactive state.

Published in the esteemed journal Nature Communications, these discoveries are poised to catalyze substantial advancements in the development and refinement of T-cell immunotherapies. The implications are profound, suggesting a pathway to engineer more effective and broadly applicable treatments. Ryan Notti, a lead author on the study and an instructor in clinical investigation within the Walz lab, concurrently serves as a special fellow in the Department of Medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where he specializes in treating patients with sarcomas—cancers originating in soft tissue or bone. Notti emphasizes the transformative potential, stating, "This newfound foundational understanding of the signaling system’s mechanics could be instrumental in redesigning the next generation of therapeutic approaches."

The T-cell receptor forms the very bedrock of virtually all contemporary oncological immunotherapies. Consequently, the fact that its fundamental activation mechanism has remained largely opaque until now underscores the critical role of basic scientific inquiry. Gunter Walz, a globally recognized authority in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) imaging and the head of the lab where this research was conducted, expressed the profound significance of this work. "It is truly remarkable that we utilize this system so extensively without a complete grasp of its inner workings – and that’s precisely where fundamental research plays its vital role," Walz commented, further asserting, "This represents some of the most significant research ever to emerge from my laboratory."

T cells are the vigilant sentinels of the immune system, constantly patrolling the body for signs of infection or cellular abnormalities, including cancer. Their ability to distinguish healthy cells from diseased ones hinges on the TCR, a multiprotein complex embedded within the T-cell membrane. This complex is exquisitely designed to recognize specific peptide fragments, known as antigens, which are presented on the surface of other cells by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, often referred to as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complexes in humans. This precise recognition event is the indispensable trigger that mobilizes the T cell’s effector functions, prompting it to proliferate, differentiate, and ultimately eliminate the compromised cell. In the context of cancer immunotherapy, this recognition process is deliberately leveraged and enhanced to direct the immune system’s cytotoxic power against malignant cells.

While the individual protein components of the TCR have been identified for many years, the precise sequence of events that initiates its activation—the very first molecular steps—has long eluded scientific elucidation. This gap in knowledge has been particularly frustrating for physician-scientists like Notti, who directly witness the limitations of current T-cell immunotherapies in patients, especially those with aggressive cancers like sarcomas, who often do not respond to existing treatments. "Deciphering this crucial step would provide invaluable insights into how information is relayed from the extracellular environment, where antigens are presented by HLA complexes, to the intracellular machinery, where T-cell signaling is initiated," Notti explained. Driven by this urgent clinical need and his background in structural microbiology, Notti, who earned his Ph.D. at Rockefeller before transitioning to oncology, proposed a collaborative investigation into this unresolved enigma with Walz.

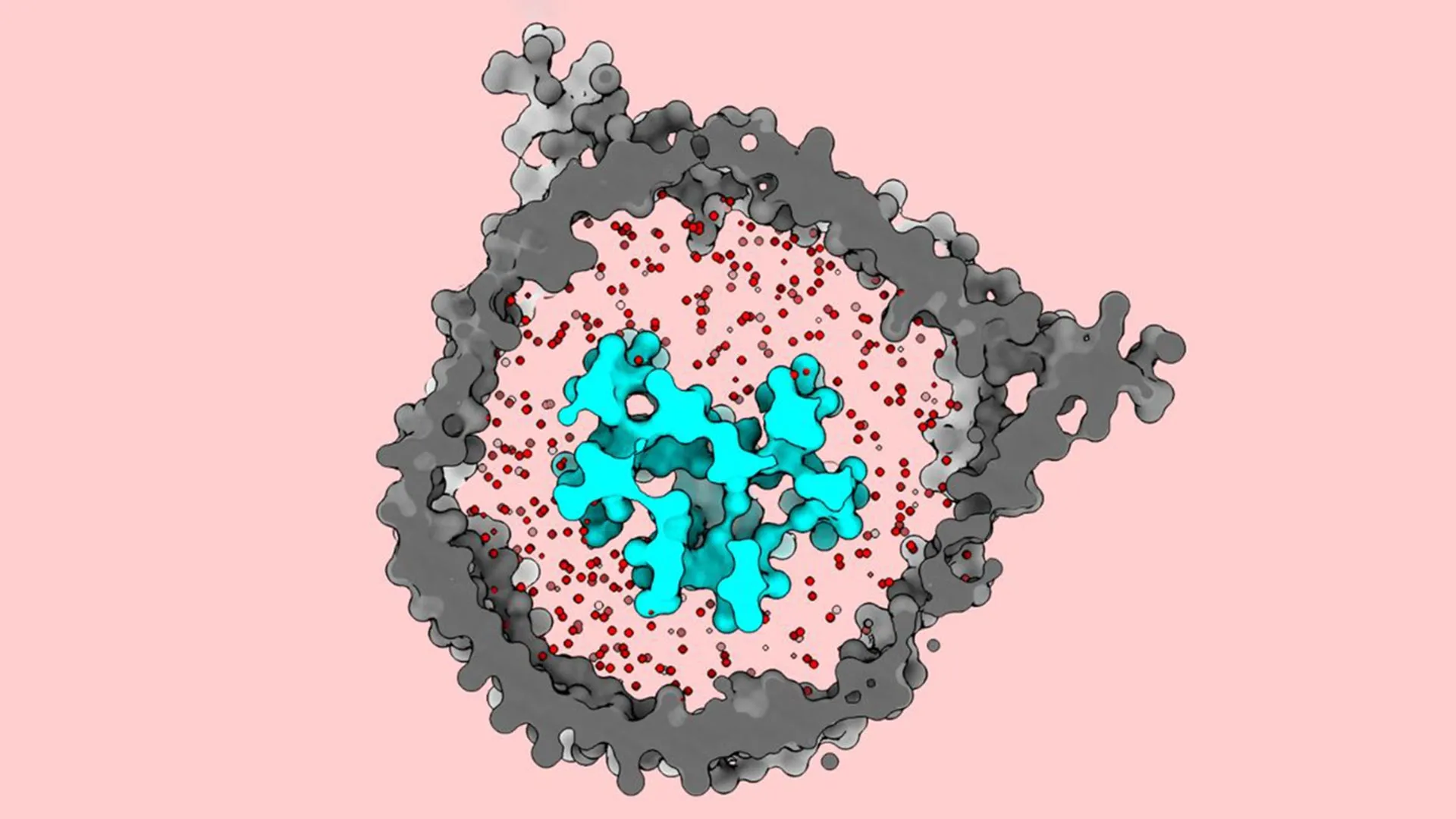

A hallmark of Walz’s laboratory is its pioneering expertise in engineering bespoke membrane environments that meticulously recapitulate the natural cellular milieu of membrane-bound proteins. This meticulous approach allows researchers to manipulate various parameters, including "the biochemical composition, the thickness and tension of the membrane, its curvature, and overall size – all factors known to influence the behavior of embedded proteins," Walz elaborated. For this particular investigation, the team embarked on the ambitious task of observing the TCR under conditions that most faithfully mirrored its native state within a living cell. They accomplished this by integrating the entire TCR complex into a nanodisc, a minuscule, disc-shaped lipid bilayer encased by a scaffold protein, held in an aqueous solution. Assembling the complete, functional receptor, which consists of eight distinct protein subunits, and successfully incorporating them into the nanodisc proved to be a formidable technical challenge, as Notti confirmed.

Significantly, previous structural analyses of the TCR often relied on detergents to solubilize and isolate the receptor. While effective for purification, detergents can disrupt the surrounding lipid membrane, potentially altering the protein’s native conformation. Walz underscored the novelty of their approach, noting that this study marked the first instance where the entire T-cell receptor complex was reconstituted within a membrane environment for high-resolution imaging, thereby preserving its physiological context.

Once the TCR was successfully embedded within the nanodisc, the researchers employed cryo-EM to capture detailed images of its structure. The resulting visualizations strikingly revealed that the receptor maintains a compact, closed conformation when in an inactive, dormant state. However, upon encountering an antigen-presenting molecule, the structure undergoes a dramatic transformation, springing open and extending outwards in a broad, expansive motion.

This observation profoundly surprised the research team. Notti recounted, "The available data when we initiated this research depicted this complex as being open and extended even in its dormant state. As far as anyone knew, the T-cell receptor was not believed to undergo any significant conformational changes upon binding to these antigens. Yet, our findings clearly demonstrated that it does, activating in a manner akin to a jack-in-the-box."

The researchers attribute this pivotal discovery to two key methodological innovations. Firstly, their painstaking recreation of the TCR’s in vivo membrane environment involved using a precise lipid mixture that accurately mimicked the composition of a native T-cell membrane. Secondly, the crucial step of reinserting the receptor into a membrane using nanodiscs before conducting cryo-EM imaging was instrumental. They posited that an intact membrane actively maintains the receptor in its closed, inactive state until genuine activation occurs. In contrast, earlier studies that utilized detergents might have inadvertently removed this critical membrane-imposed restraint, leading to a premature, artifactual opening of the receptor structure. Walz reinforced this point, stating, "It was imperative that we utilized a lipid mixture that truly resembled that of the native T-cell membrane. Had we simply employed a generic model lipid, we would not have observed this critical closed, dormant state."

The team firmly believes their findings hold immense promise for enhancing treatments that rely on the sophisticated action of T-cell receptors. Notti highlighted the pressing clinical need: "Redesigning the next generation of immunotherapies represents one of the most significant unmet clinical demands." He provided a concrete example: "Adoptive T-cell therapies are currently showing success in treating certain rare sarcomas. One can envision applying our insights to re-engineer the sensitivity of these receptors, effectively fine-tuning their activation threshold to improve efficacy."

Walz also foresees potential applications extending beyond the realm of cancer therapy. "This fundamental information could also be leveraged in the design of new vaccines," he added. "Experts in the field can now utilize our detailed structural data to gain a refined understanding of the interactions between various antigens presented by HLA molecules and the T-cell receptors. These distinct modes of interaction may have significant implications for how the receptor functions, opening new avenues for optimization in vaccine development." This breakthrough fundamentally reshapes our understanding of immune recognition and promises to accelerate the development of more effective and targeted immunotherapies and vaccines, ultimately benefiting countless patients worldwide.