For a considerable period, the prevailing scientific understanding in neuroscience posited that mature neurons, once subjected to damage or destruction, lacked the inherent capacity for regeneration. This long-standing dogma has fundamentally influenced the diagnostic frameworks and therapeutic strategies employed for addressing neurological injuries. However, the observed phenomenon of individuals frequently regaining a degree of lost functionality following traumatic events has persistently challenged this rigid tenet, prompting a critical re-examination of the underlying recovery processes. If neuronal regrowth is indeed non-existent, what then accounts for the observed rehabilitation?

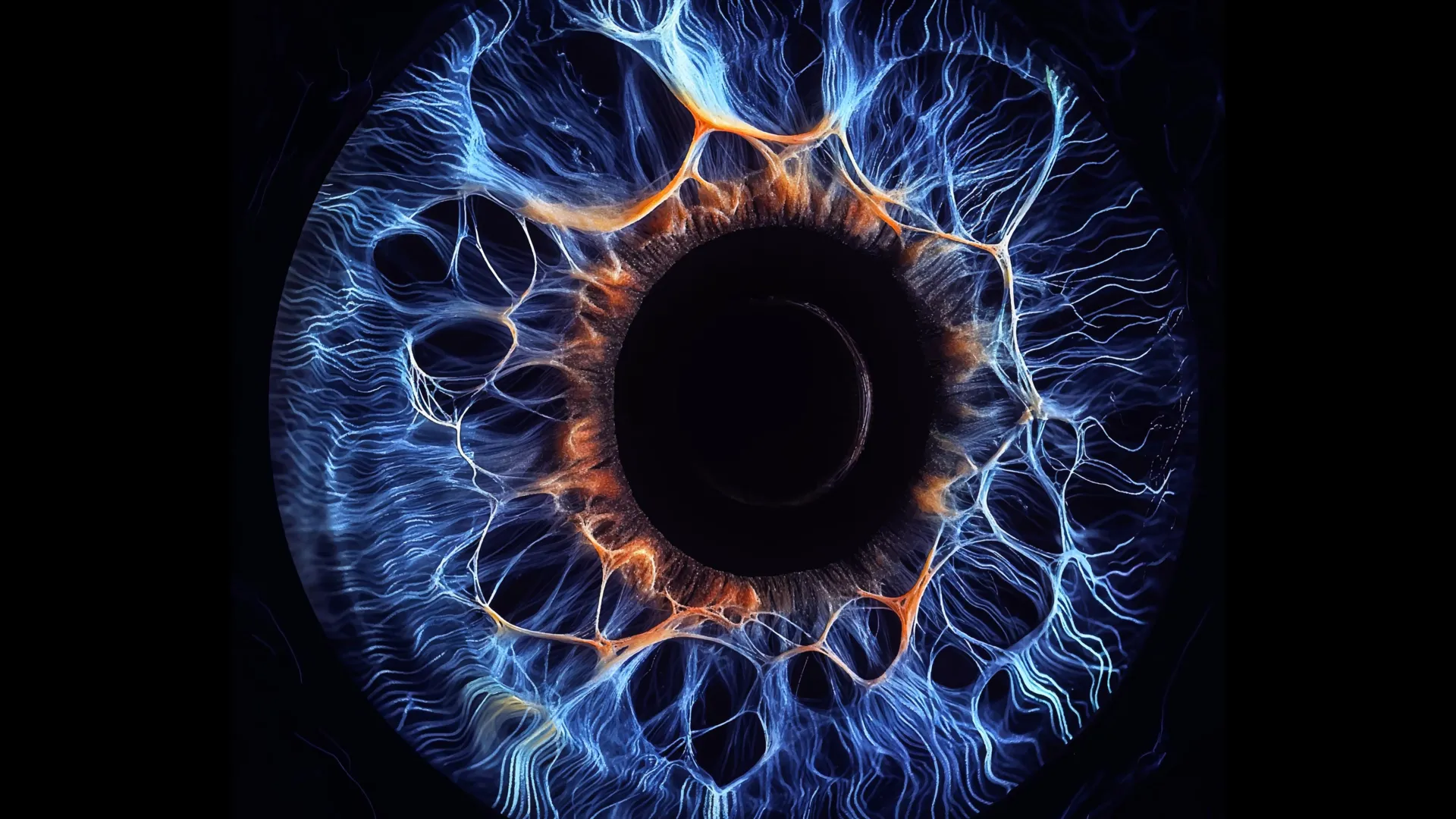

A recent publication in the esteemed journal JNeurosci provides illuminating insights into this enduring enigma. Researchers, led by Athanasios Alexandris at Johns Hopkins University, embarked on a meticulous investigation utilizing a murine model to elucidate the intricate cellular dynamics within the visual system subsequent to traumatic brain injury. The visual system, a complex network encompassing photoreceptor cells in the retina and the neural pathways that transmit visual information to the brain, is paramount for the perception of sight. Lesions affecting this system can precipitate a breakdown in the communication channels between the eye and the cerebral cortex, thereby manifesting as visual impairments.

The investigation focused on the synaptic connections linking retinal ganglion cells to neurons within the visual cortex. Rather than identifying substantial proliferation of new neuronal entities to replace those lost, the scientific team observed a remarkable adaptive response among the surviving neural elements. These resilient cells, having weathered the initial insult, initiated a process of structural remodeling.

Specifically, the surviving neurons exhibited an augmented outgrowth of dendritic and axonal branches. This phenomenon, commonly referred to as sprouting, effectively expanded their connectivity repertoire. These newly extended branches allowed the surviving neurons to establish a greater number of synaptic contacts with neurons in the brain than they possessed prior to the injury. This compensatory mechanism played a crucial role in bridging the functional gap created by the loss of other neurons. Over a defined period, the researchers noted a significant restoration in the density of connections between the retina and the brain, approaching pre-injury levels.

Crucially, the efficacy of these reconstituted neural circuits extended beyond mere anatomical reconstruction. Electrophysiological recordings and functional imaging techniques confirmed that the newly formed pathways were not simply structural placeholders; they actively transmitted neural signals with considerable fidelity. This functional reintegration underscores the remarkable plasticity of the nervous system and its capacity to adapt and recover lost capabilities even in the face of significant structural damage. The visual system, therefore, demonstrated a capacity to resume its operational duties, albeit through a reconfigured network architecture.

An intriguing facet of this research emerged with the discovery of pronounced sex-based differences in the recovery trajectories observed in the male and female mice. While the male subjects displayed robust functional recovery mediated by the compensatory sprouting mechanism, the female subjects exhibited a markedly attenuated or incomplete repair process. The restoration of retinal-to-brain connections in the female cohort did not consistently reach the same pre-injury baseline as observed in their male counterparts.

The authors of the study posit that these findings highlight a sex-dependent modulation of neural recovery mechanisms. As Dr. Alexandris articulated, the discovery of these sex differences was unexpected, yet it resonates with existing clinical observations in human populations. It is well-documented that women tend to report a higher incidence and greater persistence of post-concussion symptoms compared to men. The researchers suggest that a deeper understanding of the molecular and cellular underpinnings of the observed branch sprouting, and particularly the factors that impede or delay this process in females, could pave the way for the development of sex-specific therapeutic interventions. Such advancements could hold significant promise for enhancing recovery outcomes following traumatic brain injuries, concussions, and a spectrum of other neurological insults.

The research consortium has outlined a clear path forward for their investigations, intending to delve deeper into the biological factors that account for the divergence in neural repair between sexes. By systematically dissecting the molecular pathways and cellular signaling cascades that govern neural plasticity and resilience, they aim to pinpoint novel targets for therapeutic development. The ultimate goal is to translate these fundamental discoveries into practical strategies that can accelerate and optimize healing processes following brain injuries, thereby improving the quality of life for affected individuals. This research not only challenges long-held assumptions about neuronal regeneration but also opens up exciting avenues for personalized medicine in the field of neurology.