A decade-long pursuit of internal illumination for neurological observation has culminated in a groundbreaking advancement, enabling scientists to witness the intricate workings of the brain in unprecedented real-time detail. This innovative methodology bypasses the limitations of external light sources by empowering brain cells themselves to generate light, offering a dynamic window into neural processes. The genesis of this concept stemmed from a fundamental question: could neurons be coaxed to emit their own luminescence, thereby obviating the need for external probes and the associated experimental challenges?

Christopher Moore, a distinguished professor of brain science at Brown University, articulated the core aspiration behind this research, stating, "We started thinking: ‘What if we could light up the brain from the inside?’" He elaborated on the conventional reliance on external light for measuring and manipulating cellular activity, often through fluorescence or laser-based techniques. However, these methods are frequently hampered by the requirement for sophisticated equipment, a lower success rate, and potential invasiveness. The prevailing hypothesis was that bioluminescence, the natural light production seen in organisms like fireflies, could offer a more elegant and effective solution.

This visionary idea catalyzed the establishment of the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science in 2017. Spearheaded by a significant grant from the National Science Foundation, the hub fostered a collaborative ecosystem of leading researchers. Key figures included Moore, who serves as the associate director of the Carney Institute, Diane Lipscombe, the institute’s director, Ute Hochgeschwender from Central Michigan University, and Nathan Shaner from the University of California San Diego. Their collective mission was to pioneer and disseminate novel neuroscience tools by imbuing nervous system cells with the inherent capacity to both produce and perceive light.

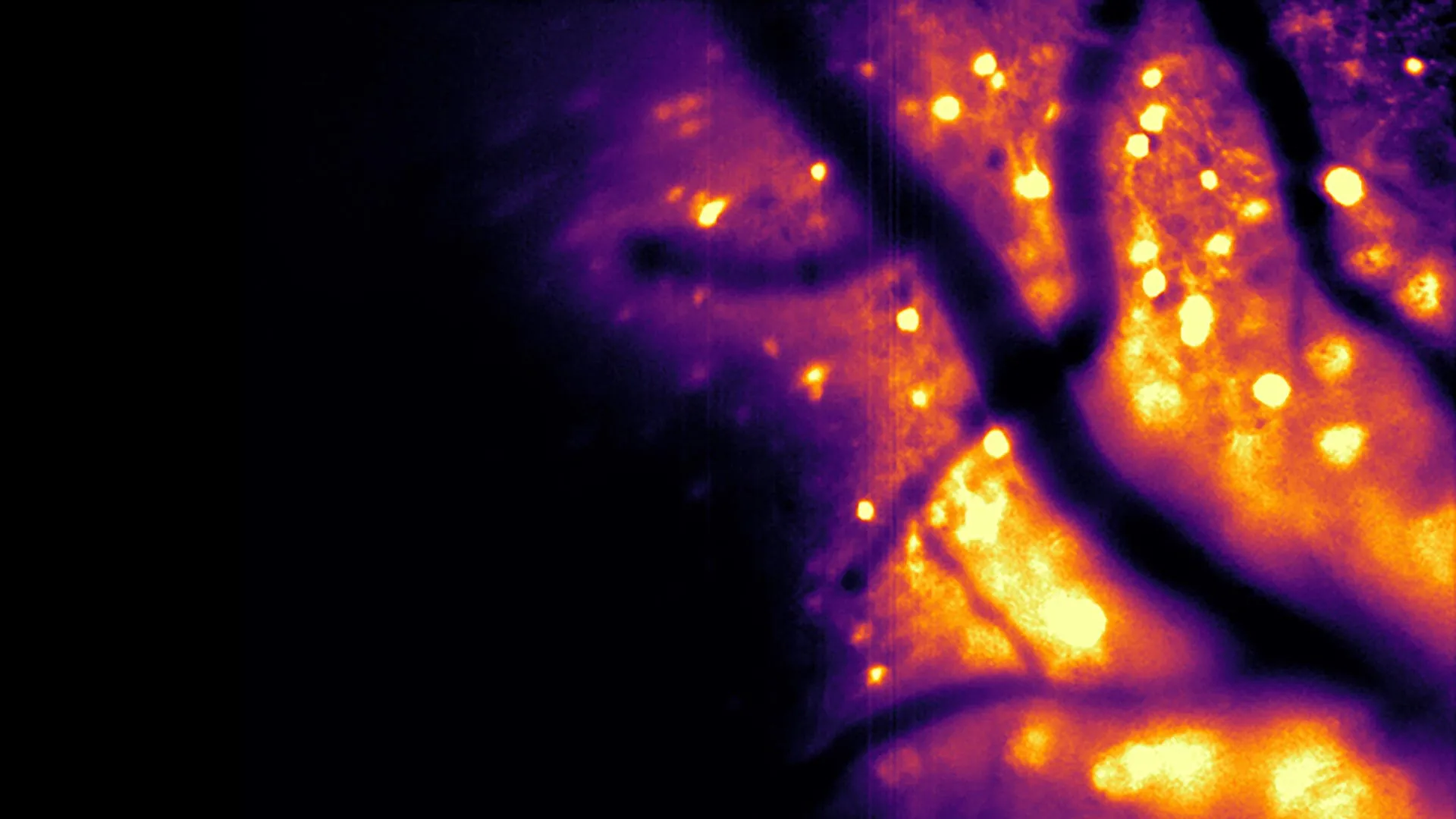

A pivotal development arising from this concerted effort is the creation of a novel bioluminescent imaging tool, meticulously detailed in a study published in the esteemed journal Nature Methods. This sophisticated instrument, christened the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor, or "CaBLAM" for brevity, possesses the remarkable ability to capture neural activity at the cellular and even subcellular levels with exceptional speed and precision. The efficacy of CaBLAM has been demonstrated in model organisms such as mice and zebrafish, facilitating continuous recordings that can extend for several hours without the necessity of any external light input.

Professor Moore lauded the ingenuity behind CaBLAM, crediting Nathan Shaner, an associate professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at U.C. San Diego, for his instrumental role in designing the core molecular architecture of the device. "CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created," Moore remarked, underscoring its exceptional performance and alignment with its intended function.

The imperative of precisely tracking the activity of living brain cells cannot be overstated, as it forms the bedrock of understanding organismal function. Current prevalent methodologies largely depend on genetically encoded calcium-ion indicators that operate via fluorescence. Professor Moore explained this process: "In the way fluorescence works, you shine light beams at something, and you get a different wavelength of light beams back." He further elaborated that this phenomenon can be rendered sensitive to calcium ions, leading to proteins that emit light of varying intensity or color based on calcium presence, thereby producing a discernible signal.

Despite the widespread adoption of fluorescence-based techniques, they are fraught with significant limitations. Prolonged exposure to high-intensity external light can inflict damage upon delicate brain cells. Moreover, the constant illumination can degrade the fluorescent molecules themselves, a phenomenon known as photobleaching, which diminishes their light-emitting capacity and curtails the duration of experimental observations. The logistical demands of delivering light to the brain, often requiring specialized equipment like lasers and optical fibers, also introduce invasiveness into experimental protocols.

In stark contrast, bioluminescent imaging offers a suite of compelling advantages. Light generation in this paradigm occurs as a result of enzymatic activity breaking down a specific molecule, thereby eliminating the need for external illumination. This inherent characteristic obviates the issues of photobleaching and phototoxic damage, rendering the approach significantly safer for the fragile neurobiological environment.

Furthermore, bioluminescence yields inherently cleaner and more interpretable imaging data. Nathan Shaner pointed out a critical drawback of conventional optical methods: "Brain tissue already glows faintly on its own when hit by external light, creating background noise." He continued to explain that light scattering within brain tissue further exacerbates this issue by blurring both incoming light and outgoing signals, leading to dimmer, fuzzier images that impede deep brain visualization. Bioluminescently generated light, however, originates from within the neurons themselves, standing out starkly against a dark background with minimal interference, as the brain does not naturally produce such luminescence. Shaner aptly described this as, "the brain cells act like their own headlights: You only have to watch the light coming out, which is much easier to see even when scattered through tissue."

Professor Moore highlighted a long-standing aspiration within the scientific community: the utilization of bioluminescence for studying brain activity, an idea discussed for decades. However, until the recent breakthroughs, the generated light lacked the intensity required for high-resolution imaging.

The breakthroughs enabling CaBLAM are rooted in a profound understanding of molecular mechanisms and a drive for enhanced sensitivity. Moore enthusiastically described the significance of the current research, stating, "The current paper is exciting for a lot of reasons." He emphasized that the newly developed molecules provide, for the first time, the capacity to observe the activation of individual cells independently, likening the experience to utilizing "a very special, sensitive movie camera to record brain activity while it’s happening."

With CaBLAM, researchers can now meticulously examine the behavior of single neurons within a living organism, including dynamic activity occurring within distinct cellular compartments. The study reported a remarkable continuous recording session lasting an impressive five hours, a feat previously unattainable with conventional fluorescence-based techniques. This extended observation period is crucial for understanding complex neurological processes. Moore noted that for the investigation of intricate behaviors and learning mechanisms, bioluminescence offers the ability to capture the entire unfolding process, while simultaneously simplifying the required experimental apparatus.

The CaBLAM project represents a component of a broader initiative within the Bioluminescence Hub aimed at developing innovative methods for both observing and modulating brain activity. One particularly intriguing experiment involves engineering living cells to emit light signals that can be detected by adjacent cells, effectively enabling neurons to communicate via light itself – a concept Moore refers to as "rewiring the brain with light." The team is also actively developing techniques that leverage calcium dynamics to regulate cellular function. As these diverse research avenues progressed, the scientists recognized a common thread: the critical need for brighter and more efficient calcium sensors. This realization has ascended to a central focus of the hub’s ongoing endeavors, according to Moore. He stressed the hub’s commitment to advancing the field by ensuring the development of all necessary foundational components.

The potential applications of CaBLAM extend beyond the realm of neuroscience. Professor Moore envisions its future use in studying cellular activity across various physiological systems within the body. "This advance allows a whole new range of options for seeing how the brain and body work," Moore posited, adding that it opens up possibilities for simultaneous tracking of activity in multiple bodily regions. He further emphasized that this significant achievement underscores the profound impact of collaborative scientific research. The development of CaBLAM involved the contributions of at least 34 scientists from partner institutions, including Brown University, Central Michigan University, U.C. San Diego, the University of California Los Angeles, and New York University. This groundbreaking work received vital financial support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.