A pioneering study published on December 18 in Nature Communications has unveiled a previously underappreciated dimension of genetic influence: the genes of an individual’s cohabitants can significantly sculpt the microbial ecosystem residing within their gut. This groundbreaking research, conducted on a large cohort of rats, suggests a dynamic interplay where an animal’s own genetic blueprint, along with that of its cage-mates, collaboratively shapes the intricate communities of bacteria inhabiting the digestive tract. The implications of this discovery could fundamentally alter our understanding of genetic contributions to health, potentially extending beyond an individual’s inherent DNA to encompass the broader social environment.

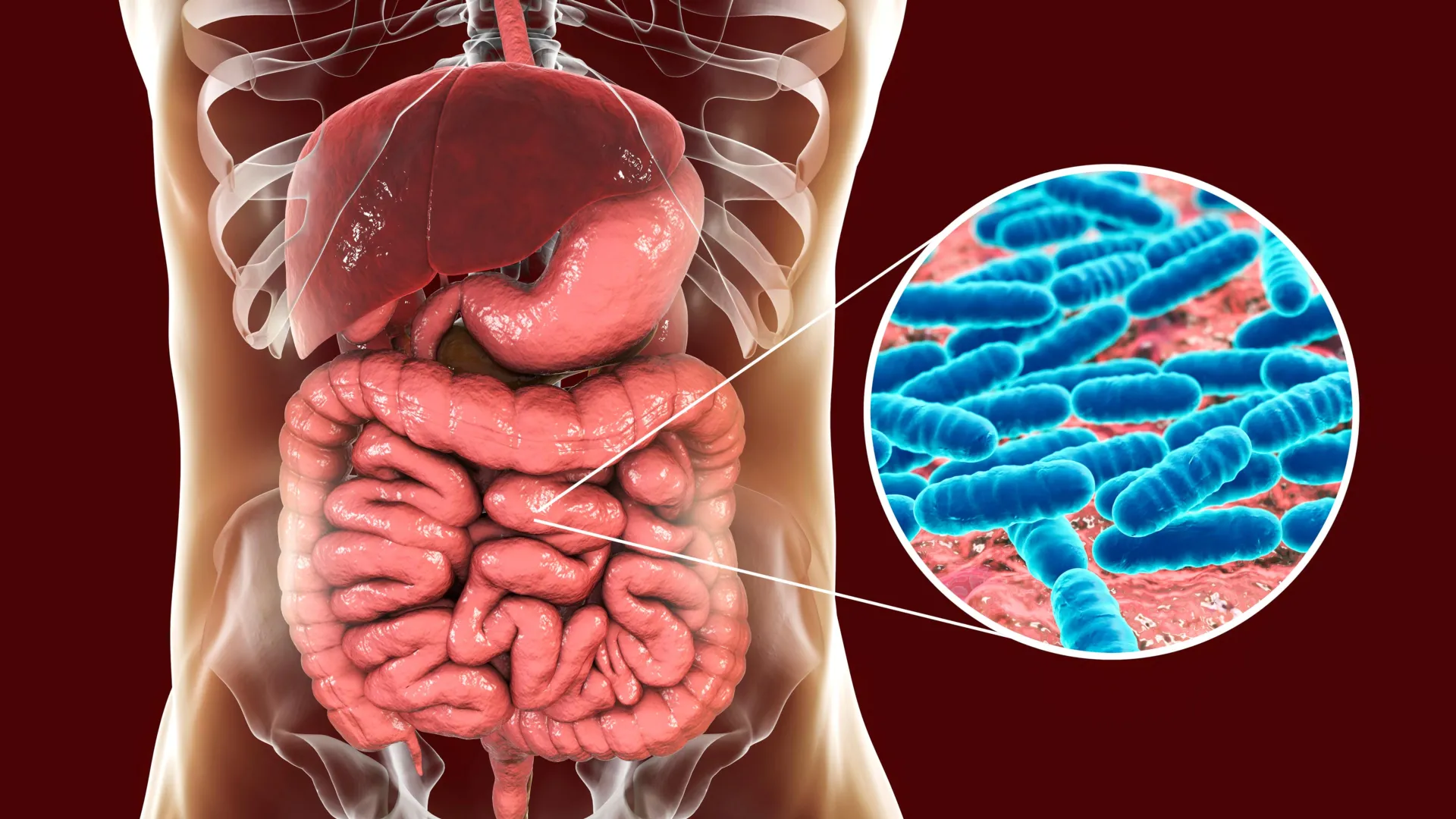

The human body is an elaborate ecosystem, home to trillions of microorganisms collectively known as the microbiome, with the gut microbiome being particularly pivotal. These microscopic residents play indispensable roles in a myriad of physiological processes, from facilitating digestion and nutrient absorption to modulating immune responses and even influencing neurological functions. While environmental factors such as diet, lifestyle, and medication are widely acknowledged as potent determinants of microbiome composition, the precise extent and mechanisms through which host genetics exert their influence have remained a complex and elusive area of scientific inquiry.

Historically, disentangling genetic from environmental factors in microbiome research has presented considerable hurdles. In humans, for instance, family members often share similar dietary habits, geographical locations, and even exposures to various microbes, making it exceptionally challenging for researchers to isolate the specific impact of genetics. This intricate web of shared experiences and inherited traits often obscures direct genetic links to microbial populations. Prior to this study, only two human genes had been reliably connected to specific gut bacteria: the lactase gene, which dictates an individual’s ability to digest lactose and thus influences milk-digesting microbes, and the ABO blood group gene, though its exact impact on gut bacteria is still being elucidated. Scientists have long suspected the existence of additional genetic ties to the microbiome but have struggled to prove them conclusively amidst the confounding variables of everyday life.

To overcome these inherent complexities and establish a more controlled experimental environment, researchers from the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and the University of California San Diego strategically utilized a rat model. Rats offer a compelling advantage due to their shared mammalian biology with humans and the ability to house them under rigorously controlled conditions, including standardized, identical diets. This experimental precision allowed the scientists to minimize external variables that typically confound human studies, providing a clearer lens through which to observe the direct and indirect effects of genetics on the gut microbiome.

The study design was ambitious, encompassing over four thousand rats, each possessing a unique genetic profile. These animals were distributed across four distinct cohorts, housed in different facilities across the United States and maintained under varied care routines. This multi-site approach was crucial, enabling the researchers to ascertain whether any identified genetic influences on gut bacteria remained consistent and robust across diverse environmental settings, thereby bolstering the generalizability of their findings. By meticulously correlating the comprehensive genetic data of each rat with detailed profiles of their gut microbiomes, the research team successfully pinpointed three specific genetic regions that consistently impacted gut bacterial communities across all four cohorts.

One of the most compelling associations identified involved a gene designated St6galnac1. This gene plays a critical role in adding specific sugar molecules to the protective mucus lining the intestinal tract. The study revealed a strong and consistent link between the presence and activity of St6galnac1 and elevated levels of Paraprevotella, a bacterium hypothesized to thrive by metabolizing these very sugars present in the gut mucus. This particular connection was observed uniformly across every experimental cohort, underscoring its significance. A second genomic locus, containing several mucin genes responsible for constructing the gut’s protective mucus barrier, was found to be associated with bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes phylum, a major group of bacteria in the gut. Furthermore, a third genetic region, encompassing the Pip gene, which is known to produce an antibacterial molecule, exhibited a correlation with bacteria from the Muribaculaceae family, a group commonly found in the guts of rodents and also present in humans.

Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of this extensive study was its unprecedented capacity to quantify the relative contributions of an individual rat’s own genes versus the genes of its cohabiting cage-mates in shaping its gut microbiome. This analysis delved into the concept of "indirect genetic effects" (IGEs), where the genes of one individual influence the traits or characteristics of another, not through direct genetic inheritance, but through the modification of their shared environment. A classic example of an IGE is how a mother’s genetic makeup can indirectly influence her offspring’s growth or immune system by shaping the uterine environment or the quality of her milk.

In this rat study, the carefully controlled living conditions were instrumental in enabling the researchers to explore IGEs within a novel context of social interaction and microbial exchange. They devised a sophisticated computational model designed to meticulously disentangle the influence of a rat’s intrinsic genetic makeup on its gut microbes from the influence exerted by the genetic profiles of its social partners. The findings were striking: the abundance of certain bacteria within the Muribaculaceae family was demonstrably shaped by both direct genetic influences (from the host rat) and indirect genetic influences (from its cage-mates). This strongly suggests a mechanism by which specific genetic predispositions can propagate socially through the exchange of microbes among individuals sharing a living space.

When these social, indirect genetic effects were incorporated into the statistical models, the overall estimated genetic influence on the three newly identified gene-microbe links dramatically increased, by a factor of four to eight times. This profound amplification highlights the extent to which the social environment, mediated by genetic interactions, can significantly contribute to the composition of the gut microbiome. Dr. Amelie Baud, a researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and senior author of the study, emphasized the significance of these findings, stating, "This is not magic, but rather the result of genetic influences spilling over to others through social contact. Genes shape the gut microbiome and we found that it is not just our own genes that matter." She further cautioned that even these amplified figures might still represent an underestimate of the true genetic contribution, noting, "We’ve probably only uncovered the tip of the iceberg. These are the bacteria where the signal is strongest, but many more microbes could be affected once we have better microbiome profiling methods." The study thus elucidates a novel biological mechanism where genetic effects from one organism can permeate through social groups via the transmission of gut microbes, subtly altering the biology of others without ever changing their core DNA.

The implications of these findings, if extrapolated to humans, are profound and far-reaching. Given the escalating evidence underscoring the critical role of the gut microbiome in maintaining human health, this research suggests that the current understanding and estimation of genetic influences on human health in large population studies may be significantly underestimated. If similar social genetic effects are at play in human societies, an individual’s genetic predispositions might not only shape their own susceptibility to various diseases but could also indirectly affect the disease risk of those in their immediate social circle, such as family members, roommates, or close friends. This perspective calls for a re-evaluation of how we assess genetic risk and consider the broader ecological context of human health.

Dr. Baud elaborated on the potential health ramifications, noting that the microbiome has established links to immune system function, metabolic health, and even aspects of behavior. However, many reported associations in human studies are purely correlational, making it difficult to ascertain cause and effect. Genetic studies utilizing animal models in highly controlled environments, like the one described, offer a powerful methodology to move beyond mere correlations and develop testable hypotheses regarding the intricate interplay between genes, gut microbes, and overall health.

Intriguingly, the research team highlighted a potential cross-species connection: the rat gene St6galnac1 shares functional similarities with the human gene ST6GAL1. Notably, previous human studies have also linked ST6GAL1 to the presence of Paraprevotella bacteria. This parallel suggests a conserved biological mechanism across species, where the specific sugar structures coating the gut mucus, influenced by genes like St6galnac1 and ST6GAL1, might be a fundamental determinant of which microbial species thrive within the digestive system.

Building on this potential cross-species link, the researchers explored how this mechanism might bear relevance to human infectious diseases, specifically citing COVID-19. Other studies have identified ST6GAL1 as a gene potentially associated with breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections in vaccinated individuals. Furthermore, Paraprevotella has been shown to induce the breakdown of digestive enzymes that the SARS-CoV-2 virus utilizes to gain entry into host cells. Integrating these observations, the researchers hypothesize that genetic variations in ST6GAL1 could influence the levels of Paraprevotella in the gut, which, in turn, might modulate an individual’s susceptibility to viral infection.

A possible connection to IgA nephropathy, an autoimmune kidney disease, was also proposed. In this condition, Paraprevotella may interact with IgA, an antibody crucial for protecting the gut lining. If altered, this IgA can leak into the bloodstream and form immune complexes that accumulate in and damage the kidneys, a hallmark feature of IgA nephropathy. These hypotheses underscore the potential for a deeper understanding of gene-microbe interactions to unlock novel insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets.

Looking ahead, the research team is eager to delve deeper into the precise mechanisms by which St6galnac1 influences Paraprevotella in rats and to map the subsequent cascade of reactions this relationship triggers within the gut and throughout the entire organism. Dr. Baud conveyed her enthusiasm, concluding, "I am obsessed with this bacterium now. Our results are supported by data from four independent facilities, which means we can do follow up studies in any new setting. They’re also remarkably strong compared with most host-microbiome links. It’s a unique opportunity." This sentiment reflects the profound potential of this discovery to open new avenues in personalized medicine, public health, and our understanding of the invisible yet powerful connections that bind us through our microbial inhabitants.