In the silent expanse of the International Space Station (ISS), a remarkable biological drama has unfolded, showcasing how life, even at its most fundamental viral and bacterial levels, can dramatically alter its evolutionary trajectory when removed from Earth’s familiar gravitational embrace. A groundbreaking study, published in the esteemed open-access journal PLOS Biology, details the surprising adaptations observed in bacteriophages – viruses that prey on bacteria – and their bacterial hosts, Escherichia coli, during their sojourn in the near-weightless environment of orbit. This research, spearheaded by Phil Huss and his team from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers profound insights into the plasticity of life and opens unexpected doors for combating terrestrial health challenges.

The intricate dance between viruses and their bacterial targets is a cornerstone of microbial ecosystems, a perpetual evolutionary arms race where each side continuously develops new strategies to outmaneuver the other. Bacteria, for instance, can cultivate novel defenses to repel viral invaders, while viruses, in turn, innovate methods to bypass these burgeoning resistances. While these dynamic interactions have been meticulously dissected under terrestrial conditions, the introduction of microgravity presents a unique set of variables. The absence of significant gravitational pull not only influences the physiological processes of bacteria but also alters the physical mechanics of encounters between viruses and their cellular prey, thereby disrupting the established patterns of interaction.

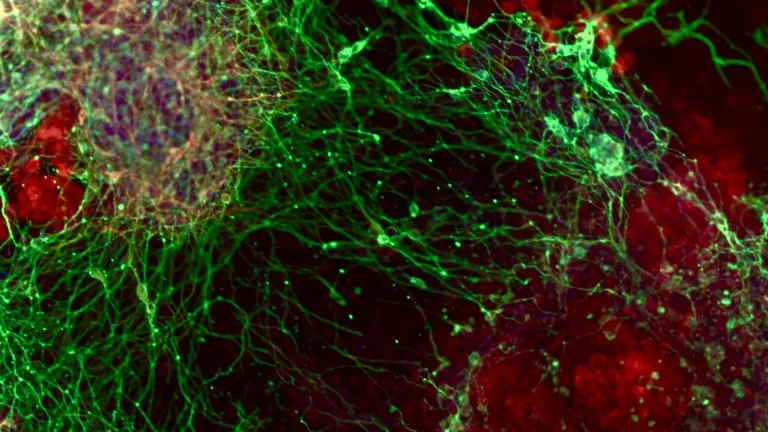

Despite the known influence of microgravity on cellular behavior, the specific nuances of how phage-bacterial dynamics are reshaped in this extraterrestrial setting have remained largely unexplored. To bridge this knowledge gap, Huss and his collaborators embarked on a comparative experiment, juxtaposing two cohorts of E. coli samples, each infected with the T7 phage. One set was subjected to the standard conditions of Earth-based incubation, while the other was transported to the ISS for cultivation in its unique microgravity environment.

Initial observations from the space-borne samples revealed a discernible, albeit delayed, success in T7 phage infection of the E. coli hosts. However, a deeper dive through whole-genome sequencing unveiled striking divergences in the genetic mutations that arose in both the bacterial hosts and the viral invaders when comparing the Earth-bound samples against their orbital counterparts. The phages that journeyed to space gradually accumulated a distinct set of genetic alterations, which scientists postulate may have conferred enhanced infectivity or a superior ability to latch onto the receptor sites on the bacterial cell surfaces. Concurrently, the E. coli residing in microgravity developed mutations that appeared to bolster their defenses against phage attacks and improve their overall resilience in the weightless conditions.

To further scrutinize these evolutionary shifts, the research team employed a sophisticated, high-throughput analytical method known as deep mutational scanning. This technique allowed for an exceptionally detailed examination of alterations within the T7 phage’s receptor-binding protein, a critical component responsible for initiating the infection process. The findings from this granular analysis underscored significant discrepancies between the mutations observed in microgravity and those that occurred under Earth’s gravity. Further investigations conducted on Earth linked these space-induced modifications in the receptor-binding protein to a notable increase in their efficacy against specific strains of E. coli that are implicated in human urinary tract infections and possess an inherent resistance to the T7 phage.

This pioneering research unequivocally demonstrates the immense potential of conducting phage research aboard the ISS. Such investigations can unlock novel perspectives on microbial adaptation, with implications that extend far beyond the confines of space exploration, potentially offering tangible benefits for human health here on Earth. The authors themselves emphasize this point, stating, "Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth. By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth."

The implications of this study are multifaceted. By understanding how viruses adapt to novel environments, scientists can gain invaluable knowledge about the fundamental principles of evolution and the resilience of biological systems. The identification of phages with enhanced activity against drug-resistant pathogens is particularly significant in the ongoing global battle against antimicrobial resistance, a growing public health crisis. The ability to engineer phages with such potent capabilities, informed by their evolutionary journey in space, offers a promising new frontier in the development of therapeutic agents. This research underscores the interconnectedness of scientific inquiry, where exploring the extremes of the cosmos can yield practical solutions for earthly challenges. The study serves as a potent reminder that even in the seemingly barren vacuum of space, life finds a way to adapt, evolve, and, in doing so, reveal profound secrets that can benefit humanity. The collaborative efforts of scientists from different nations aboard the ISS, supported by various funding agencies, have culminated in a discovery that transcends borders and holds the potential to impact global health strategies for years to come. This work, supported by grants from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the Anandamahidol Foundation, exemplifies how dedicated research, coupled with international cooperation, can push the boundaries of scientific understanding and deliver tangible advancements for society.