The global medical community stands on the precipice of a significant advancement in the ongoing battle against cancer, as researchers at the University of Southampton have unveiled a novel strategy designed to dramatically intensify the body’s intrinsic defenses. This pioneering approach, detailed in the esteemed journal Nature Communications, centers on engineering sophisticated antibodies to empower the immune system’s primary cellular assassins, known as T-cells, enabling them to identify and eradicate malignant tumors with unprecedented efficacy. The implications of this discovery could redefine the landscape of cancer immunotherapy, offering renewed hope for patients who currently derive limited benefit from existing treatments.

For decades, the promise of harnessing the immune system to combat cancer remained largely theoretical. However, in recent years, immunotherapy has emerged as a revolutionary pillar of oncology, alongside traditional chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. Treatments such as checkpoint inhibitors, which release the brakes on immune cells, and CAR-T cell therapies, which re-engineer a patient’s own T-cells to target cancer, have transformed the prognosis for many individuals facing aggressive malignancies. Despite these breakthroughs, a substantial portion of patients do not respond to current immunotherapies, or their responses are not durable. This persistent challenge underscores the critical need for innovative mechanisms that can overcome the sophisticated evasive tactics employed by cancer cells, particularly by bolstering the initial activation signals required for a robust anti-tumor immune response.

Central to the immune system’s anti-cancer arsenal are cytotoxic T lymphocytes, often referred to as CD8+ T-cells. These specialized white blood cells are tasked with patrolling the body, recognizing abnormal or infected cells, and initiating their destruction. Their ability to effectively kill cancer cells hinges on a complex activation process, which typically requires two distinct signals. The first signal involves the T-cell receptor recognizing specific antigens presented by cancer cells. The second, equally crucial, signal comes from co-stimulatory molecules on the T-cell surface interacting with their corresponding ligands on antigen-presenting cells or, ideally, the tumor cells themselves. Without this co-stimulation, T-cells may become anergic (non-responsive) or undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death), failing to mount a sustained attack.

One such vital co-stimulatory receptor on T-cells is CD27. When activated by its natural ligand, CD70, CD27 sends a powerful signal that propels T-cells into a state of heightened activity, promoting their proliferation, survival, and cytotoxic function. This natural activation occurs robustly during acute infections, where the body produces ample CD70 to marshal a potent immune response. However, cancer cells frequently lack the expression of CD70 or downregulate it, effectively depriving T-cells of this crucial second signal. Consequently, even if T-cells recognize tumor antigens, they receive only a weak, insufficient activation cue, leaving them unable to fully engage and neutralize the cancerous threat. This immunological loophole represents a significant barrier to effective anti-tumor immunity and has been a focal point for researchers seeking to enhance immunotherapy outcomes.

Existing therapeutic antibodies, while revolutionary in their own right, often possess a conventional bivalent or Y-shaped structure, featuring two identical antigen-binding sites. This design inherently limits their capacity to bind to and activate more than two target receptors simultaneously. While effective for blocking inhibitory pathways or tagging cells for destruction, this two-point attachment often proves inadequate for inducing the intense, localized clustering of co-stimulatory receptors like CD27 that is essential for a robust T-cell activation signal. The challenge, therefore, lay in designing an antibody format capable of orchestrating a more potent, multi-point interaction, thereby mimicking the efficacy of natural ligand-receptor engagement.

The breakthrough achieved by the Southampton team, led by Professor Aymen Al Shamkhani, lies in their innovative engineering of antibodies with a quadrivalent design, meaning they possess four binding arms rather than the conventional two. This structural modification is not merely an increase in binding sites; it represents a fundamental shift in how these therapeutic molecules interact with immune cells. The quadrivalent architecture allows the antibodies to engage multiple CD27 receptors on a single T-cell simultaneously. More profoundly, these specially crafted antibodies also recruit a second immune cell type into the interaction. This ingenious mechanism forces the aggregated CD27 receptors to cluster together more tightly and efficiently on the T-cell surface. This induced proximity and heightened density of activated receptors dramatically amplifies the intracellular signaling cascade, effectively overriding the weak signals typically encountered in the tumor microenvironment and closely replicating the powerful activation seen during natural immune responses.

Professor Al Shamkhani articulated the complexity of this scientific journey, stating, "Our fundamental understanding of how the body’s natural CD27 signal invigorates T-cells was a foundational piece of the puzzle. However, translating that intricate biological knowledge into a tangible therapeutic agent presented a formidable challenge. Antibodies are inherently stable and reliable molecules, making them exceptional candidates for drug development. Yet, the standard, naturally occurring antibody format simply lacked the potency we required to achieve optimal T-cell activation. This necessitated a complete re-imagining and creation of a more effective version." His remarks underscore the blend of deep biological insight and innovative biochemical engineering that characterized this project.

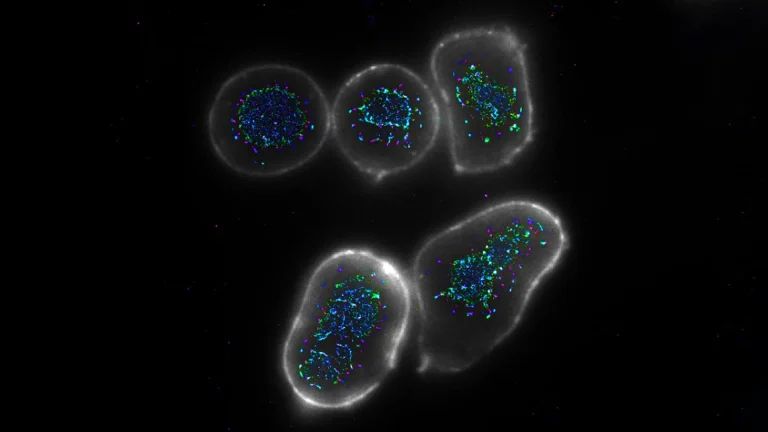

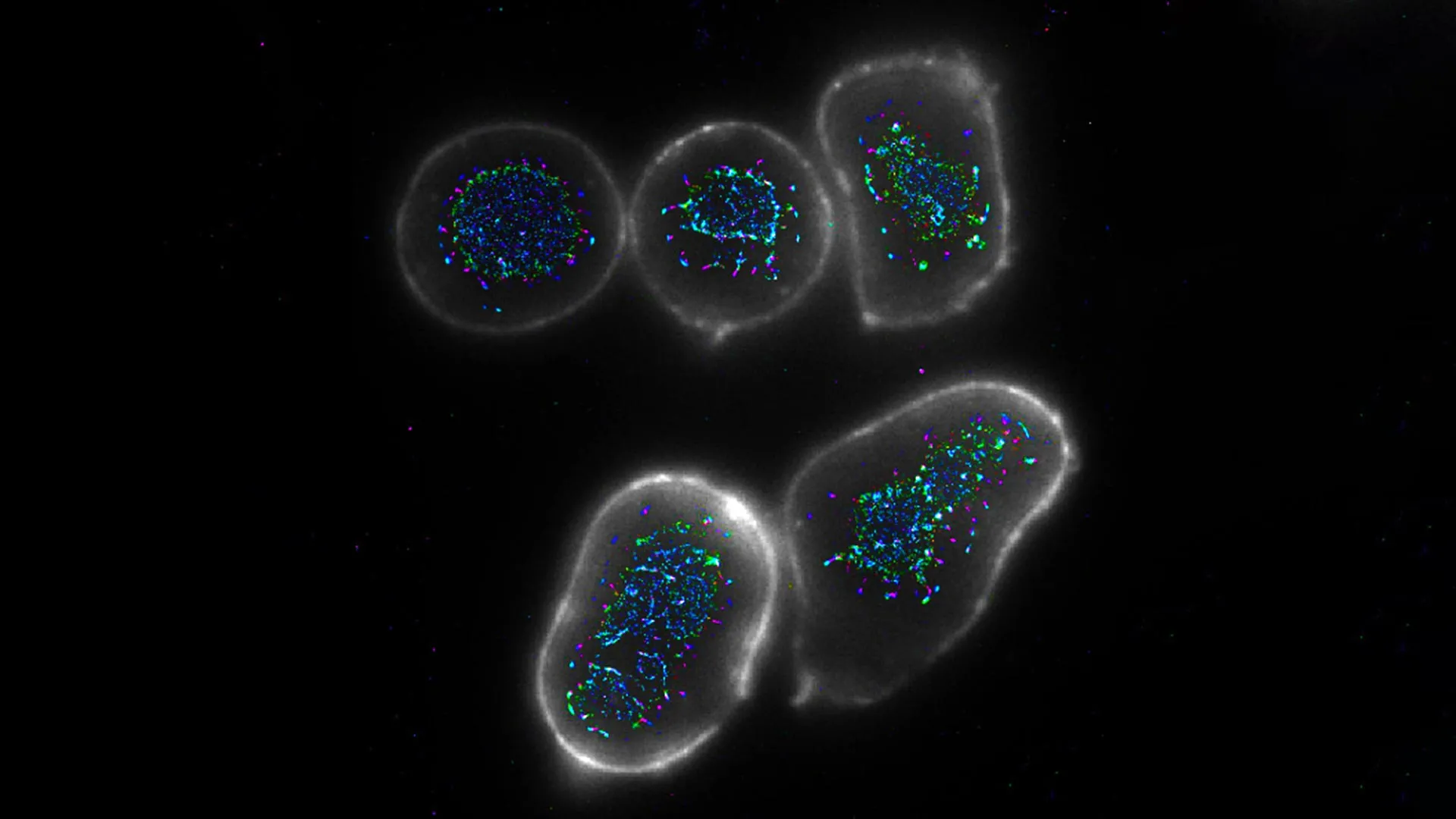

Rigorous laboratory testing provided compelling evidence for the superior performance of these novel quadrivalent antibodies. In both in vitro experiments using isolated human immune cells and in vivo studies conducted in sophisticated mouse models, the engineered antibodies demonstrated a significantly enhanced ability to activate CD8+ T-cells compared to their conventional bivalent counterparts. This augmented activation translated directly into a more robust and sustained anti-tumor response, characterized by increased T-cell proliferation, elevated production of critical cytotoxic cytokines like interferon-gamma, and ultimately, a more effective destruction of cancer cells. These preclinical results strongly suggest that by making the CD27 pathway more amenable to therapeutic targeting, this research provides a crucial blueprint for the development of next-generation immunotherapy treatments that can more fully leverage the inherent power of the immune system.

The potential implications of this quadrivalent antibody design extend beyond CD27. This innovative approach offers a generalizable strategy for manipulating other co-stimulatory pathways that are critical for T-cell function but are often under-activated in the context of cancer. By demonstrating a method to induce optimal receptor clustering and signal amplification, the Southampton team has paved the way for a new class of immunotherapeutic agents. Future research will undoubtedly explore applying this multi-armed antibody concept to other immune receptors, potentially unlocking novel avenues for boosting anti-cancer immunity or even modulating autoimmune responses.

As Professor Al Shamkhani further elaborated, "This methodological advancement holds immense promise for refining future cancer treatments, enabling the immune system to operate closer to its absolute peak potential." This vision encapsulates the aspiration of many in the field: to move beyond simply releasing immunological brakes and towards actively driving immune cell function to achieve curative outcomes. The journey from preclinical discovery to clinical application is long and arduous, requiring further optimization, comprehensive safety evaluations, and eventually, human clinical trials. However, the foundational work has been meticulously laid.

This groundbreaking research was generously supported by Cancer Research UK, a testament to its potential impact. It also highlights the critical role played by the Centre for Cancer Immunology at the University of Southampton, an institution dedicated to fostering cutting-edge research and developing innovative approaches in the burgeoning field of cancer immunotherapy. The successful development of these engineered antibodies represents not just a scientific triumph but a beacon of hope, promising a future where the body’s own immune system can be meticulously trained and powerfully equipped to overcome even the most formidable cancers.