The period of adolescence represents a crucial juncture in human development, characterized not only by profound social and physiological transformations but also by significant advancements in neural architecture and cognitive function. During these formative years, sophisticated mental faculties such as strategic foresight, logical deduction, and intricate decision-making undergo continuous maturation. Despite this recognized importance, a comprehensive understanding of the intricate mechanisms governing the sculpting of the brain’s complex neural networks throughout this critical developmental phase remains elusive to the scientific community.

At the fundamental level of neural connectivity lies the synapse, the specialized junction where neurons communicate, facilitating the transmission of information across the brain’s intricate circuitry. For a considerable duration, prevailing scientific consensus posited a trajectory of synaptic development wherein their numbers steadily augmented throughout childhood, only to undergo a substantial reduction during adolescence. This long-standing paradigm gave rise to the widely accepted theory of excessive "synaptic pruning," a neurobiological process involving the elimination of underutilized or weak neuronal connections. This theoretical framework has frequently been invoked to explain the etiology of various neuropsychiatric conditions, with schizophrenia, a disorder frequently manifesting in symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thought processes, often being linked to this mechanism of connection pruning.

However, groundbreaking new research has emerged, challenging this deeply entrenched scientific viewpoint. A distinguished cadre of investigators from Kyushu University has recently presented compelling evidence that fundamentally questions this established perspective on adolescent brain development. Their meticulously conducted study, disseminated in the esteemed journal Science Advances on January 14th, reveals a paradigm shift: the adolescent brain does not merely engage in the systematic elimination of existing connections. Instead, it is actively involved in the formation of novel, highly concentrated clusters of synapses within specific anatomical regions of neurons during this developmental epoch.

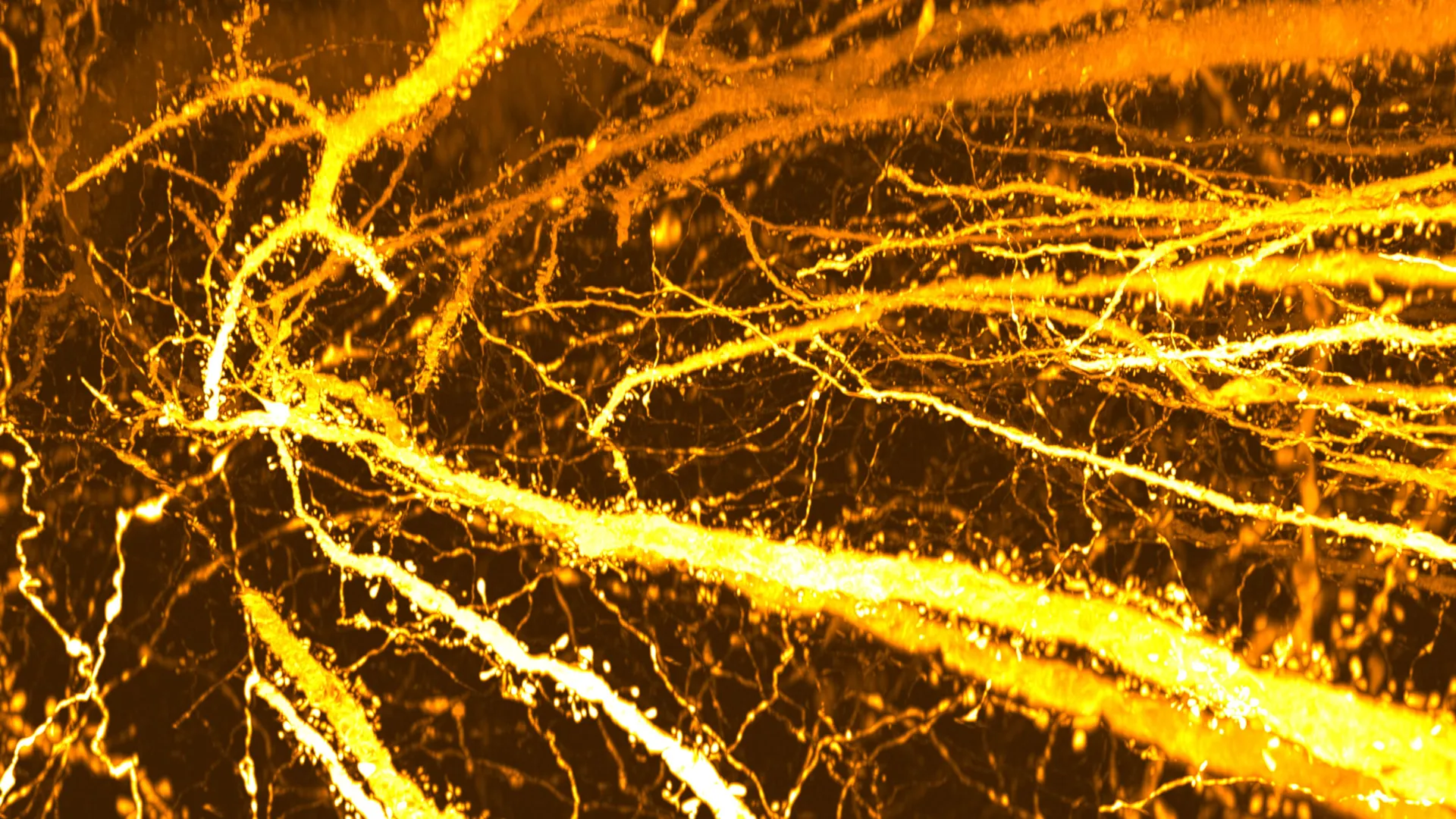

Professor Takeshi Imai, affiliated with Kyushu University’s Faculty of Medical Sciences, shared insights into the genesis of this transformative research, stating, "Our initial research endeavors were not specifically directed towards the study of brain disorders." He elaborated on the unexpected discovery, explaining, "Following the successful development of a sophisticated high-resolution analytical tool for synaptic evaluation in 2016, we turned our attention to the cerebral cortex of mice out of sheer scientific curiosity. Beyond appreciating the inherent aesthetic beauty of the neuronal structures, we were profoundly surprised to identify a previously undocumented region exhibiting an exceptionally high density of dendritic spines – the minute protrusions extending from dendrites that serve as the principal sites for the formation of excitatory synapses."

The cerebral cortex, a highly complex structure integral to higher-order cognitive functions, is organized into six distinct layers. These layers collaborate synergistically to construct exceptionally intricate neural circuits that underpin our cognitive capabilities. Professor Imai and his research associates concentrated their detailed investigations on neurons residing within Layer 5. This specific layer plays a pivotal role in integrating information from a multitude of sources and subsequently transmitting signals outward, constituting the cortex’s ultimate output. Due to this critical functional role, neurons within Layer 5 effectively serve as a central command post, orchestrating the brain’s information processing capabilities.

To facilitate an in-depth examination of these particular cellular structures, the research team employed SeeDB2, a specialized tissue-clearing agent developed by Professor Imai’s group. This was judiciously combined with the application of super-resolution microscopy. This powerful synergistic approach enabled the researchers to render brain tissue transparent, thereby facilitating the unprecedented mapping of dendritic spines across entire Layer 5 neurons with remarkable fidelity and detail. This innovative methodology provided a panoramic view of synaptic organization that had been unattainable with prior techniques.

The highly detailed cartographic data generated by this advanced imaging revealed a pattern that defied prior expectations. A distinct and localized segment of the dendrite exhibited an unusually high concentration of dendritic spines, coalescing to form what the researchers have termed a "hotspot." Subsequent in-depth analysis confirmed that this specific hotspot is conspicuously absent in the brains of young individuals but emerges and develops significantly during the adolescent period.

To precisely delineate the temporal emergence of this critical developmental change, the researchers meticulously tracked spine distribution across various developmental stages in their animal models. In two-week-old mice, a stage preceding weaning, dendritic spines were observed to be distributed with relative uniformity across the entire neuron. However, a significant transformation was noted between three and eight weeks of age, a period encompassing early childhood through adolescence. During this interval, spine density experienced a marked and rapid increase within a singular region of the apical dendrite. Over time, this localized and accelerated growth culminated in the formation of a densely packed synapse hotspot. Professor Imai commented on the implications of these findings, asserting, "These discoveries strongly suggest that the long-established hypothesis concerning ‘adolescent synaptic pruning’ warrants a thorough re-evaluation."

This novel discovery may also offer significant insights into the developmental pathways of certain neurological disorders. Ryo Egashira, the lead author of the study and a graduate student at Kyushu University’s Graduate School of Medical Sciences at the time of the research, explained, "While synaptic pruning is a widespread phenomenon occurring across dendrites, it appears that synapse formation also occurs within specific dendritic compartments during adolescent cortical development. Consequently, disruptions to this localized formation process may represent a key etiological factor in at least a subset of schizophrenia cases."

In an effort to rigorously investigate this hypothesis, the researchers examined mice exhibiting genetic mutations in genes that have been previously implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, including Setd1a, Hivep2, and Grin1. Their observations indicated that early development in these genetically modified mice proceeded typically, with spine density appearing normal up to approximately two to three weeks post-birth. However, a striking divergence was observed during adolescence, wherein synapse formation was significantly impaired, thereby preventing the appropriate development of the characteristic hotspot.

For many years, schizophrenia has been predominantly conceptualized as a condition primarily driven by an excessive loss of synapses. The current findings introduce a compelling alternative perspective: that impairments in the formation of new synapses during adolescence might play a more critical role in the development of the disorder. Nevertheless, the researchers prudently emphasize that their study was exclusively conducted on rodent models, and the extent to which these precise neurobiological processes translate to primates or humans remains an open and critical question requiring further investigation.

Looking toward the future trajectory of brain development research, Professor Imai expressed his aspirations, stating, "Moving forward, our objective is to precisely identify which specific brain regions are engaged in the formation of these newly developing synaptic connections during adolescence. This knowledge will be instrumental in understanding which neural circuits are actively being constructed during this vital developmental window. A deeper comprehension of how and when these connections are established has the potential to significantly advance our understanding of both fundamental brain development and the underlying mechanisms of neuropsychiatric disorders."